After years of waiting, the National Education Policy (NEP) of 2020 was finally approved by the Union Cabinet on the 28th of July, resulting in a deluge of press coverage and punditry on its objectives. Why? Because the NEP marks a significant step towards defining the education objectives of the next decade (we have covered its major hits and misses in this article for India Development Review.)

However, beyond reanalyzing the NEP, what is the larger state of India’s education system that the policy seeks to strengthen? While academic parameters of evaluation have their own merits, many practitioners require an action-oriented framework to understand the NEP with, so as to be able to implement it usefully.

Our team at Leadership For Equity has been privy to just how educational policies are formulated and implemented at the national and state levels. Based on that experience, this article does two things. First, it contextualizes an existing framework to help quantitatively rate various sections of the NEP. Second, it recommends policy opportunities for state governments and civil society organizations to immediately start working on.

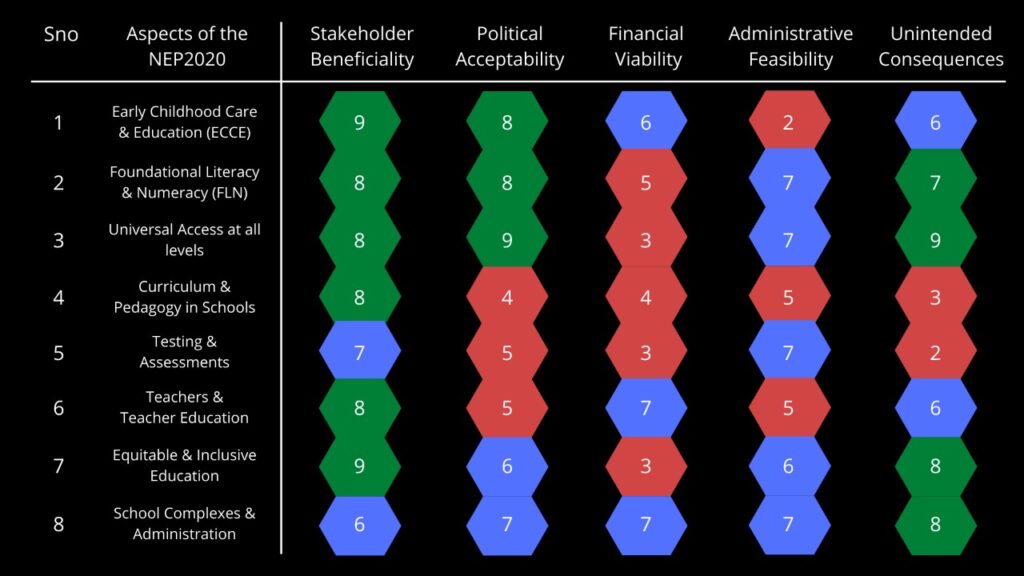

Evaluating the NEP 2020

“If ideas have to fructify, they have to be politically acceptable, socially desirable, technologically feasible, financially viable, administratively doable and judicially tenable.”

That’s Anil Swarup, the former School Education and Literacy Secretary of India, who among many high-profile postings briefly led the development of the NEP. Adding to these parameters though, it’s also important to foresee the potential risks of well-intended policy, or, its ‘unintended consequences’ [1].

Combining these frameworks, the following five parameters were developed to rate various components of the NEP based on Leadership For Equity’s experience working with Maharashtra’s education administration:

- Stakeholder Beneficiality (SB): The likelihood of the idea directly impacting the stakeholders it intends to reach.

- Political Acceptability (PA): The alignment of the idea with political priorities, and the likelihood of any opposition. That is, high political acceptability = low likelihood of opposition.

- Financial Viability (FV): The extent of the financial burden on the exchequer. That is, high viability = low cost.

- Administrative Feasibility (AF): The preparedness of the current administrative staff to implement the idea. That is, high feasibility = high preparedness.

- Unintended Consequences (UC): Are there any unintended adverse effects the idea or policy will bring about when implemented? That is, a lower rating = higher chance of unintended consequences.

From the ratings above, for the effective implementation of the NEP, there are two constraints that can be controlled: financial viability and administrative feasibility. Through our suggested headstart action items for state governments, we hope that necessary steps are taken to increase the smooth implementation of various aspects of the NEP. Additionally, we hope that the collaborative opportunities mentioned below for Corporate Social Responsibility initiatives (CSRs) and NGOs will mitigate the unintended consequences resulting from the policy.

Aspect 1: Universal Early Childhood Care & Education (ECCE)

Risk Overview

- There is a need to resolve the logistical hassle of implementing ECCE, the responsibility for which is unclearly divided between three state departments: Education, Women and Child Welfare (WCD), and Tribal Affairs.

- While the policy commits to improving the woeful infrastructure of Anganwadis, it remains silent on improving the plight of workers and helpers who work there, and developing training programs for them.

Headstart Actions for State Governments

- Define a clear division of ministerial and operational responsibilities at all administrative levels, right from the State at the top, to the Anganwadi at the bottom. The state’s WCD should be responsible for providing infrastructural inputs and support and the SED should be responsible for monitoring and driving child-level learning outcomes.

- Through a Government Order (GO)/Government Resolution (GR), clearly define that maintaining the quality of education and nutrition delivered at ECCE/Anganwadi centres will be the sole responsibility of the School Education Department (SED).

- Map 100% of all Angawandi centres to nearby primary schools for co-locational support, as well as to smoothly facilitate the transition to elementary education.

- Revisit the salary and service conditions of ECCE and Anganwadi workers: increase their current remuneration from ₹4,500 a month, to at least ₹10,000 a month.

Collaborative Opportunities for CSRs/NGOs

- Support the SCERTs in developing a 6-month training curriculum for Anganwadi workers, especially in the areas of online content, joint certification opportunities, and implementation.

- CSRs can adopt rural and tribal Anganwadis to upgrade infrastructure.

Aspect 2: Achieving Foundational Literacy & Numeracy (FLN) for India’s Students

Risk Overview

- The success of large scale missions has always depended on a shared understanding of the indicators of success–which aren’t defined yet in the NEP.

- The main risk of financial viability concerns the state’s commitment to hiring teachers and increasing access to reading material for children. Despite past efforts to fill teacher vacancies, the processes have seen inordinate delays. Additionally, to date, we have found that libraries are either under-equipped or underutilized.

Headstart Actions for State Governments

- Define the criteria and indicators for ‘foundational literacy and numeracy’ aligned with the National FLN mission proposed in the NEP.

- Set up a dedicated FLN Project Management Unit (PMU) under the Education Secretary’s Office or Commissionerate of Education, consisting of academic advisors, subject experts, and consultants experienced in state-level administration.

- The PMU must ensure the smooth implementation and rigorous monitoring of the state’s FLN Mission.

- In consultation with excellent teachers, design a level-based foundational learning program, with structured pedagogies and learning materials, and a state-wide implementation plan.

- Invest in multilingual, age-appropriate reading material up to Grade 5, to be circulated to all children in print, and in online formats through DIKSHA. This should be done alongside a robust program to integrate these materials into the child’s daily routine.

Collaborative Opportunities for CSRs/NGOs

- Realign programs to meet the state’s FLN goals by supporting local school networks and communities, especially in aspirational districts or blocks with historically low scores.

- Create open-source and age-appropriate print and digital multilingual content to promote reading and mathematics.

- Organize mass volunteering programs to ensure the time-bound achievement of FLN in their areas of operation.

Aspect 3: Universal Access to Education For All Children

Risk Overview

- The long-awaited demand for extending the right to education (RTE) from the current age bracket of 6-14 to 3-18 has been suggested in the NEP; however, the financial burden on the exchequer as a result of this move is a big concern.

- Over the past decade (or pre-COVID-19) over 95% of children had access to primary education, in line with RTE. The remaining 5% are left out due to systemic issues of urban homelessness and child labour, which require concerted efforts across government departments, law enforcement, and communities to resolve–measures much larger than those mentioned in the NEP.

Headstart Actions for State Governments

- Build a 5-year phased roadmap of the minimum financial spending required to integrate K-12 under the RTE for all children under the new age bracket, with a year-on-year increase in allocation.

- Re-energize the State Commission for the Protection of Child Rights (SCPCR) with strong leadership. The SCPCR is legally mandated to ensure a child’s rights are protected; access to continued education, irrespective of their background, is one of those mandated rights. Empower it to convene programs cutting across ministries and law-enforcement agencies to reach universal access goals.

- Increase students’ access to secondary schools by upgrading current schools, building new schools, and encouraging highly accountable Public-Private Partnership (PPP) school models.

- Build a 10-year phased roadmap for extending digital access to all children from Grades 5-12, through Internet access and digital devices.

- Securely track all children with a unique ID linked to a student’s Aadhaar card. Child IDs should be created right at the Anganwadi/ECCE level and be used up till the 12th grade, to facilitate the smooth integration of government schemes, services, and admissions processes with a student’s education (Editor’s note: please note the security disclaimer on the necessary privacy protocols for such solutions available below).

Collaborative Opportunities for CSRs/NGOs

- In collaboration with government agencies, design and implement creative learning models for the continuous education of children facing challenging circumstances, such as urban homelessness, child-labour, seasonal migration, and low connectivity (common in tribal areas.)

- CSRs can promote innovations to boost access, either through time-bound Development Impact Bonds (DIB), or the targeted funding of organizations focused on overcoming access barriers.

- CSRs can launch targeted scholarships to increase the access of marginalized communities to education.

Aspect 4: Reforming Curriculum and Pedagogy in Schools

Risk Overview

- Providing quality English language learning, even as a second or third language, has been an issue in regional-medium schools across the country, aside from being a contentious political issue. A lack of clarity on how to provide quality English language instruction, might propagate this status quo of poor instruction in schools.

- The policy envisages providing excellent multilingual education, and instruction in newer subjects like coding and Indian knowledge systems. Currently, teachers lack the capacity to achieve the same, while the larger talent pool of teachers also remains small.

Headstart Actions for State Governments

- The state should decisively formulate, communicate, and adopt a clear 3-language policy. Emphasis on English language fluency right from Grade 1 should be emphasized, regardless of medium of instruction.

- Build a 5-year roadmap for teacher recruitment and capacity building to successfully facilitate the adopted language policy.

- The State Curriculum Framework built by the SCERT, should prioritise a maximum of 3-5 targeted ‘Concentrated-Curricular skills’ and values, which can consist of 21st Century Skills and Social-Emotional Skills.

- Promote autonomy for districts to adopt either National Level (NCERT designed) or State Level (SCERT designed) Mathematics and Science learning materials as per their discretion.

Collaborative Opportunities for CSRs/NGOs

- Create proof points of the successful integration of specialized subjects, such as coding, computational thinking, and Indian knowledge systems into school structures.

- Proactively partner with state governments to develop the curriculum and training modules for these specialized subjects.

Aspect 5: Reforming Testing & Assessments

Risk Overview

- Various states have invested in testing mechanisms; however, what proves expensive is the sheer human and financial cost of conducting assessments themselves. Between 2016-2018, based on our organizational experience, an estimated 20 crores were spent annually on the census assessments conducted in Maharashtra. The surveys for the crucial Annual Status of Education Report survey cost ₹100 per child. And so, many similar programs which started enthusiastically, have been axed due to budgetary constraints.

- “Teaching to the test” and the increasing pressure faced by students, teachers, and schools to achieve high test scores are historical concerns in educational systems that have adopted national standardized assessments.

Headstart Actions for State Governments

- Restructure the State Secondary and Higher Secondary Boards (SSC/HSC) into the State Testing Agency (STA). The STA can be tasked with the creation of a holistic ‘State Assessment Framework’, aligned to the national counterpart, to help create a holistic, accessible, and inclusive assessment system for each stage of schooling (that is, for Grades 3, 5, 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12.)

- Reduce potential exam stress and anxiety by planning assessment cycles such that all children in Grades 1-9 take part in only one standardized assessment per year; children in Grades 10-12 can take part in a maximum of two standardized assessments per year.

- Develop question banks–of thousands of questions–for students to practice with, and to support them at the three broad levels of learning: ASER (Foundational level), NAS (National Level), and PISA (International Level). These banks should be aligned with the learning outcome(s) defined by the State.

- Design and develop a secure AI-based student assessment platform to capture formative assessment data, that ultimately generates automated, holistic, progress-driven report cards. This should be designed to be used and accessed by all levels of the system, from teachers to parents. (Editor’s note: please note the security disclaimer on the necessary privacy protocols for such solutions available below.)

Collaborative Opportunities for CSRs/NGOs

- Create working examples of 360 degree, holistic student report cards capturing not just academic performance, but also the students’ socio-emotional well-being, life-skills, physical fitness, talents, and artistic abilities. Can also develop holistic formative and summative assessment patterns to be considered by governments for adoption and scaling.

- CSRs can provide targeted funding for open source products that assist the integration of AI into student assessment and support, and are in service of creating public goods.

- Design and implement programs for exam-related stress and anxiety management that children and parents may face.

Aspect 6: Supporting Teachers & Improving Teacher Education

Risk Overview

- Despite the repeated recommendations by numerous Joint Review Missions, SCERTs and District Institutes of Education and Training (DIETs), which are key to the sustenance of teacher reforms, have not been infrastructurally upgraded, administratively empowered, or financially strengthened.

Headstart Actions for State Governments

- Develop a teaching education framework, aligned to the National Framework, for the entire teacher’s life-cycle, including pre-service and in-service education.

- Administratively, financially, and infrastructurally strengthen the state’s SCERT and DIETs to lead the training of teachers and field officers (whether online or in blended formats).

- Design a benchmarking framework for Teacher Education Institutes (TEIs), aligned with the national guidelines. Ensure SCERT and DIETs are adequately empowered to ensure that action is taken against low-quality or spurious TEIs.

- To generate more data for informed policy decisions and smooth administration, design and adopt a secure AI-based platform which integrates end-to-end teacher management cycles, and includes data on recruitment, resource mapping (transfers), salary processing, and career progression (promotions). Design an AI-driven learning management system (LMS) that integrates online course consumption, assessments of teacher learning, training credits mapping, and reimbursement of Travel & Dearness allowances. (Editor’s note: please note the security disclaimer on the necessary privacy protocols for such solutions available below.)

Collaborative Opportunities for CSRs/NGOs

- In partnership with SCERTs, create online and blended training modules for teachers and field officers that can be hosted on state platforms.

Aspect 7: Enabling an Equitable & Inclusive Education System

Risk Overview

- Initiatives driving equity and inclusivity in education always demand substantial budgetary allocation. Without long-term sourcing and spending commitments, key inequity issues will prevail for decades to come.

- Entrenched societal prejudices against people from marginalized backgrounds, genders, and sexualities, as well as the differently-abled, are the underlying factors contributing to exclusion, which remain historically unaddressed.

Headstart Actions for State Governments

- Prepare a time-bound financial plan to source and spend the state component of the ‘Gender Inclusion Fund’; focus on activities not just aimed at girls, but also on the inclusion of transgender children, and the sensitization of boys.

- Re-energize the leadership of State Commission for Protection of Child Rights to convene a new State-Level Social Integration Mission that drives the integration of Children with Special Needs (CWSN), girl students, transgender students, and learners from religious minorities into school systems in a time-bound manner. Ensure the accountability of directorates within the School Education Department.

- Increase the scope and definition of inclusivity in the curriculum, and ensure that school cultures address the needs of the LGBTQIA+ community.

- Recruit full-time special educators at the block level, for a 1:15 teacher-student ratio, who are supported and managed by DIET faculty and Block Education Officers (BEO).

- Implement targeted schemes and programs for the inclusion of children belonging to religious minorities, especially Muslim children.

- Build a state-level single-stop-shop information packet (consisting of a website, app, and booklet) detailing all the schemes and services available for all social, economic, and religious categories of students across the K-12 system. This packet should also list out the steps to access them.

Collaborative Opportunities for CSRs/NGOs

- In collaboration with government agencies, design, and implement creative school and learning models to help overcome the most well-known barriers to educational access for girls (early marriage, inaccessible bathrooms, and sanitation, etc.), and children with special needs, etc.

- Design creative pedagogical models to nurture a school culture that is inclusive of diverse gender identities, social backgrounds, and religions.

- To increase the enrolment figures of marginalized communities, CSRs can adopt Kasturba Gandhi Balika Vidyalayas and specific schools in aspirational districts to upgrade infrastructure and accessibility issues.

- CSRs can launch targeted scholarships to increase the access of marginalized communities to education (that is, for girls, members of the LGBTQIA+ community, religious minorities.)

Aspect 8: Creating New School Complexes

Risk Overview

- The idea of a ‘School Complex’ is around 40 years old, and suggests administratively grouping 10-15 schools dispersed across neighbouring hamlets for easier management.

- The current school organizational structure in several states is at a ‘Cluster’ level, and is operated by clusters heads (CRCs). This might suggest an overlap with the school complex idea that is being proposed; or, that the school complex is merely a continuation of cluster-level school management.

Headstart Actions for State Governments

- Undertake a rigorous school mapping exercise of all the primary and secondary schools at the village and cluster level in the state, to clearly demarcate the areas where School Complexes may be developed, and to facilitate the necessary administrative restructuring for the same.

- Build a 5-year financial roadmap to ensure that the mobility of students and teachers is enabled in all school complexes, potentially with a vision to have one bus allocated per school cluster, which can be jointly managed by autonomous school management committees and local authorities.

- Set up an online platform to map the needs and requirements of school complexes to enable prioritized government and CSR aid.

Collaborative Opportunities for CSRs/NGOs

- CSRs can donate buses to school complexes to enable the mobility of the stakeholders such that they access the benefits of the school complex model.

- CSRs can adopt school complexes, particularly in aspirational districts to upgrade infrastructure and accessibility.

Disclaimer: We encourage that these ratings are viewed as a guiding framework for discussing and debating what constitutes a good education policy, and not as an evaluation framework. The framework described here is in no way scientifically evaluated. All the ratings are purely based on individual reasoning, and are influenced by our experiences working in the education sector for the last ten years. They do not reflect Leadership for Equity’s organizational beliefs.

With regard to the three suggestions made above regarding robust AI-based data monitoring systems, we strongly believe that the state education department should enact robust data security and privacy laws to ensure the secure protection of data. Governments should include clear, comprehensive guidelines on privacy policies, made available to the public and all levels of the administration, especially pertaining to third party vendors’ usage and access, and the consequences of misusing data.

[1] Influenced by ‘A Framework for Analyzing Public Policies’, Published by the National Collaborating Centre for Healthy Public Policy, Quebec, in 2012.

Feature image courtesy of Gayatri Malhotra on Unsplash. | Views expressed are personal.

[…] suggest that adequate financing of the profession via the public exchequer is not on the cards. The emergence of for-profit players in Continuous Professional Development and teachers’ testing, and in ‘out-sourcing’ models […]