Co-authored by Chirag Chinnappa, Gopika Kumaran and Aishwarya Birla

Pushed to the edge, the Cauvery river is the latest to join the growing list of rivers demanding a living entity status, alongside the Ganga, Yamuna and Narmada. A living entity or ‘legal personhood’ status gives the said entity the “rights, powers, duties and liabilities of a legal person”. The entity may be human or non-human (like corporations, deities and trusts) and will have the ability to defend its own rights in a court of law.

An organization with a unique agenda, The Codava National Council (CNC), has undertaken efforts to protect the lifeline of the South, “Mother Goddess Cauvery”. This year, it organized a jatha (vehicle procession) along the Cauvery to raise awareness about its health and the need for autonomy in Kodagu. Beginning at its origin in Talacauvery in Kodagu, the jatha stretched until Poompuhar where the Cauvery confluences with the Bay of Bengal on Tamil Nadu’s coast.

“The river will die like river Saraswati that disappeared centuries ago,” warns CNC President Nachappa NU. More importantly, the CNC believes that attaining this legal status for a natural resource is a step towards recognising its rights to protection and regeneration, rather than simply a resource to fulfil human needs.

The Cost of Living

In 2017, New Zealand’s Whanganui River received its living entity status thanks to the local Whanganui Maori tribe, who battled for over 140 years for the river to be recognized as “their ancestor”. But the cultural roots behind such legal battles concerning the environment often obscure larger vested geopolitical interests.

In India, the push for declaring the Ganga and Yamuna rivers as living entities was motivated by the fact that the sacred rivers are considered Goddesses by most Hindus. Just three months after it was declared a living entity by the Uttarakhand High Court, the Supreme Court revoked the status in May citing administrative complications in representing the river.

Similarly, for the Cauvery, the CNC argues that the river is one of the saptanadi (seven sacred rivers) of the Vedic period and that it “is our duty to preserve, respect, protect and use the river like a living monument”. Religious significance aside, last December, the Cauvery and its tributary Arkavathi had dangerously high counts of faecal coliform, possibly attributed to open defecation alongside the river. Chemical effluents from dyeing and other heavy industries have added to its woes. With reduced water inflow and rainfall, the Cauvery does not reach the sea for four months a year.

Source: TOI

Interestingly, the jatha organized by the CNC had more than one motive. At its culmination in Poompuhar, the CNC proposed three resolutions. The first demanded the ‘Legal Person’ status “on the lines of Ganga, Yamuna and Narmada” for the sacred river. It is unknown whether the SC’s overturning of the Ganga and Yamuna verdicts has been accounted for by the CNC.

The second resolution is rooted in the CNC’s ethos — that is, demanding for a separate ‘Codavaland’. Claiming an autonomous region with the status of a Union Territory, the jatha’s resolution has far-reaching consequences for India as a whole, and Karnataka as we know it to be.

It must be made clear that the CNC’s movement to attain Cauvery’s living status is intrinsically linked to its claim for Codavaland and its stressed resources

The final resolution was for the holy points at Talacauvery and Poompuhar to be treated as divine sanctuaries, akin to Mecca-Medina or the Vatican.

Unlikely as it may be, furthering the appeal for Cauvery’s personhood could be a way for the newly formed Karnataka government to temporarily placate the separatist tendencies of the CNC. Still, the river’s tumultuous history between Southern states is unlikely to be resolved in the near future: the verdict on the Cauvery Water Management Authority and Cauvery Water Regulatory Committee are yet to be debated in Parliament.

River #cauvery is dying. Looks at the amount of hyacinths and sewage mixing with river. Taken from railway bridge near erode. @ChennaiRains pic.twitter.com/MEnjaSVwvZ

— Statistically Hiding (@balaj824) June 24, 2018

Remember, rivers cannot speak for themselves in a court of law. As a non-human entity, it is assigned legal custodians (like parents for a minor) to represent its rights and best interests. Here, the human conception of nature’s ‘best interests’ is subjective and can easily be compromised by political agendas and biases. The formation of a representative body for the living entity, comprised of Advocate Generals (from Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Puducherry) will definitely blur the lines on how the river’s rights ought to be interpreted.

The Paradigm Shift Required

Modern developmental laws’ irreversible effect on natural structures on our planet has garnered the worry of most governments. The Paris Agreement is a strong example of countries coming together to recognise human beings as being a part — and not the centre — of life on the Earth.

Some 200 years ago, Americans wouldn’t bat an eyelid if courts denied Blacks citizenship rights because they were simply “a subordinate and inferior class of beings”. For centuries, courts restricted females’ roles in society to the confines of bearing offspring and nothing beyond. Without legally sanctioned rights, women, slaves and persons of colour were ‘things’ to be used as resources by a society. Yes, legally representing the Cauvery in a similar way (as deities or corporations) will require a macroscopic re-evaluation of India’s legal system. Yet, the CNC’s movement is analogous to historical movements that granted rights to mere ‘things’, enabling them to live dignified lives.

Recognizing the living status of the Cauvery can enable a new life for the river, if not return it to its previous abundance. For any activity that exploits or denigrates the river’s health, there would be no requirement to prove its knock-on effects on humans. Polluting the Cauvery, its tributaries or the ecosystems it sustains would in itself directly violate the river’s fundamental “right to life”. This is nothing new; the UN has pushed for countries to make the right to a healthy environment a fundamental one for its citizens.

Watering a Slippery Slope

Rivers or mountains are not bonafide persons and do not have the unique cognitive and emotional capacities of animals, or even a sentient robot. Besides, if the Cauvery were to attain personhood (so to speak), then what restricts every natural form from attaining this status? Where do we draw the line between any inanimate object (to which a collective attaches inherent value) and a living entity?

As good-willed as it may appear, championing the CNC’s movement could easily be a slippery slope for the uninformed. Besides the cause of saving ‘Mother Cauvery’, granting a living status — as in the cases of Ganga and Yamuna — could instigate all-too-familiar battles between the federal nature of the Indian State and the water management duties of the states that the river flows through.

For example, it will be interesting to see what happens when the Cauvery’s right to life (to freely flow) is confronted with the 101 dams already built in its basin across four states’ borders. Will the respect accorded to this status be uniform across states and districts? For starters, a river cannot be assigned to a single cultural denominator. In Tamil Nadu, the Cauvery seeps into the works of prolific Tamil composers and cultural agents, regardless of their caste or community backgrounds. Even beyond agricultural purposes, Tamil Nadu could lay as much of a cultural and historical stake to the Cauvery as any other state.

From legislations like using Cauvery water for more homes in Bengaluru to diverting river water for the farmers of select districts like Mandya, judicial orders on incumbent governments’ developmental plans (which clash with the river’s fundamental rights) will complicate the enforceability of this personhood status.

Clearly, transposing New Zealand’s model of the Whangunui River to an Indian river fraught with political contestation and riparian livelihood is not a wise strategy. Deeming the Cauvery (legally) alive could lead to new forms of discrimination between the river and the life-systems dependent on it.

The CNC’s movement presents an opportunity to re-orient the politicized Cauvery debate and the potential tradeoffs between natural protection and resource extraction. Even so, one thing is clear from all these legal pushes and shoves. The Codava National Council’s jatha — much like any other movement to accord rivers with living statuses — is born out of the inability of consecutive federal governments (and India’s peoples) to maintain specific standards for enforcing river Cauvery’s protection. Now, Her people are fighting battles like never seen before.

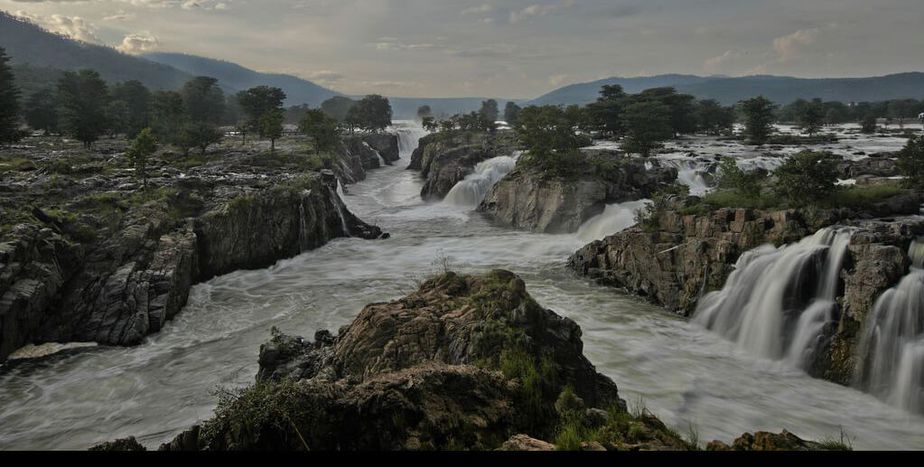

Featured image courtesy Chandru