In July 2021, the Uttar Pradesh State Law Commission released a draft Bill for creating a law that will work towards the control, stabilization, and welfare of the population of the state. The Commission had sought comments from the public on the Bill titled “Uttar Pradesh Population (Control, Stabilisation and Welfare) Bill, 2021”, which suggests that the Bill is still in its planning phase.

Legislation seeking population control is not unknown to Indian jurisprudence. In fact, various state governments like Haryana and Maharashtra have come up with their own laws that seek to achieve some form of population control, making provisions that disqualify persons who have more than two children from contesting in municipal elections, for example. These provisions were first challenged before the Supreme Court in Javed & Ors vs State of Haryana (2003), where the Court whilst observing that contesting for an office in a Panchayat is not a fundamental right, went on to state:

“If anyone chooses to have more living children than two, he is free to do so under the law as it stands now but then he should pay a little price and that is depriving himself from holding an office in Panchayat in the State of Haryana. There is nothing illegal about it and certainly no unconstitutionality attached to it.”

However, in a recent Supreme Court hearing of a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) which sought the implementation of steps to control the country’s rising population, the Central Government submitted that it does not plan on implementing a mandatory ‘two-child norm’ policy and reiterated that “the Family Welfare Programme in India is voluntary in nature, which enables couples to decide the size of their family and adopt the family planning methods best suited to them according to their choice without any compulsion”.

Despite this ‘voluntary’ stance, various state governments have attempted to incentivize couples to adopt family planning by offering monetary incentives, through legislation or policy. After all, population control and family planning are listed in the Concurrent List of the Seventh Schedule of the Indian Constitution under ‘economic and social planning’, meaning that both the Union as well as state legislature can enact laws concerning the same.

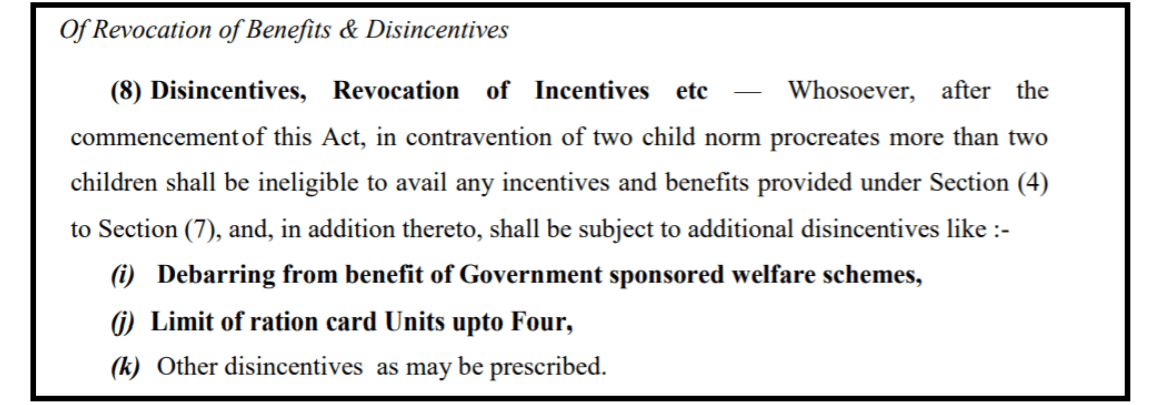

The Bill proposed by the Uttar Pradesh Law Commission is unique in that it proposes very serious disincentives and disqualifications, including restricted access to food distribution schemes, disqualification from applying for government jobs, a bar on promotions for existing government employees, ineligibility for receiving any government subsidy, etc. for the purpose of achieving population control.

The Bill risks setting a coercive precedent for endangering women’s health and impinging upon their agency and freedom in the interest of ‘population control’. Read in tandem with recent rulings on citizens’ rights and liberties, the Uttar Pradesh population control bill will find it difficult to withstand the scrutiny of our courts. Instead, women need to be granted control over their bodies, have increased access to contraception, and be educated about the need for family planning.

Legislation that Strips Vulnerable Women of their Freedoms

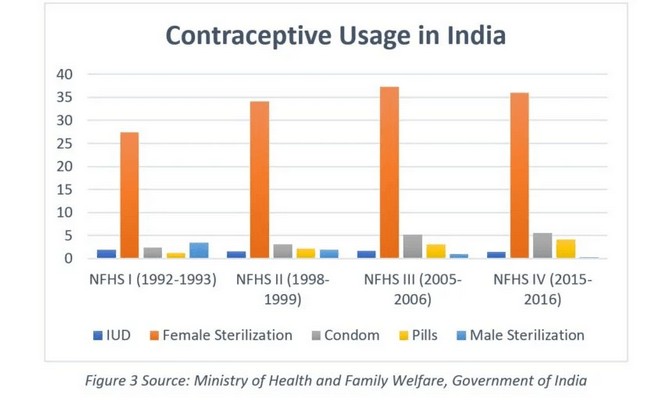

As for mandating one spouse to undergo a sterilization procedure in order to claim benefits, the Bill overlooks the various safer contraceptive methods that are available to citizens instead. It is important to note that as per the National Family Health Survey 4 (NFHS 4), only 0.1% of men in Uttar Pradesh used sterilization as a method of family planning, while 17.3% of women in Uttar Pradesh used sterilization. In fact, there seems to exist a national policy framework advocating for sterilization; the 2013 Manual for Family Planning lays down a framework for compensation in the event of a death or any complications after a sterilization procedure. Addressing both acceptors as well as service providers of sterilization, it seems to encourage people to adopt permanent methods of Family Planning.

Undergoing Sterilization for the Sake of the State and Family

We must not forget the dark history that India has with regards to sterilizations, including but not limited to the 2014 Chhattisgarh massacre and the intervention of the Supreme Court’s landmark decision banning mass sterilization. While it is clear that women would face the disproportionate brunt of the Bill’s provision to undergo sterilization, it is also important to highlight that the female sterilization process, which involves sealing or tying the fallopian tubes, is an irreversible one, and is much more complicated to perform when compared to male sterilization or a vasectomy.

In a recent study, the percentage of women who “regretted undergoing sterilization” increased from 5% during the NFHS 1 (1993) to 7% in NFHS 4 (2016), even as the total number of women undergoing the process increased by seven times in the same period. Those whose process was performed in a public health facility expressed higher regret. The complications of sterilization, its invasive nature, and the complications that can follow clearly outweigh the need for any state government to incentivize this form of family planning.

Who Will Be Worst Affected?

It doesn’t end with sterilization. Regardless of the methodology or terminology used, population control policies, particularly those that focus on fertility reduction in the Global South have been criticized by feminist scholars for years. Not only are such policies a challenge to reproductive autonomy but the very indiscriminate impact of such policies on marginalized women has also been called to question. The Indian Supreme Court in its landmark judgment on mass sterilizations also reflected on this and pronounced:

“It is necessary to re-consider the impact that policies such as the setting of informal targets and provision of incentives by the Government can have on the reproductive freedoms of the most vulnerable groups of society whose economic and social conditions leave them with no meaningful choice in the matter and also render them the easiest targets of coercion”

In her analysis of the violence caused by India’s population policy, Kalpana Wilson concludes that population policies promoted by neoliberal global capital which are incorporated into Indian national family planning programs both mobilize and re-embed the structural subordination of women belonging to marginalized and vilified communities. “This is made possible by the long-term construction of particular women’s lives as devalued and disposable, and of their bodies as excessively fertile and therefore inimical to development and progress,” Wilson writes. A study conducted by Mahila Chetna Manch in the five states of Andhra Pradesh, Haryana, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, and Rajasthan analyzed the consequences of the ‘two-child norm’ policy on women’s status, child sex ratios, and women’s participation in governance. The findings also highlighted that such a policy had an adverse impact on marginalized women, leading to desertion by husbands, and sex-selective unsafe abortions.

If there is anything to learn from China’s ‘one-child policy’, it is the impact that it had on the country’s sex ratio and the rise in the cases of girls being abandoned and sex-selective abortions. India’s ‘missing girl’ phenomenon is well-documented, with a prediction of at least 6.8 million fewer girls being born in the country due to sex-selective abortions by 2030, a practice that has been outlawed in the country. Interestingly, the estimates suggest that the highest deficits in the birth of girls will occur in Uttar Pradesh. In terms of method and intent, the Bill will disproportionately hamper marginalized women’s autonomy and endanger their health, all in the interest of incentivizing population control.

Can the Bill Stand The Test Of Courts? Legal Challenges Abound

A detailed reading of the draft Bill suggests that it seeks to promote a “two-child norm” which it defines as “an ideal size of a family consisting of a married couple with two children”. Here, “married couple” is a couple whose marriage has been solemnized legally, where the boy and girl are not less than 21 and 18 years of age respectively. The Bill then proceeds to explain that for the purpose of the Act, married couples will refer to one set of “man” and “woman”, though the parties may be common for other marriages if their personal laws allow so. To claim any incentive as provided under UP’s proposed population control Act, a man and a woman are required to first enter into a legal marriage, have at least one child, and then for either of them to get a sterilization procedure.

An Arbitrarily Marriage-Centric and Heteronormative Approach

The draft Bill is completely silent on its applicability to parents who are live-in couples, unmarried couples, non-heteronormative couples, or single parents. Going by the language of the draft Bill itself, it appears that persons not falling under the definition of “married couples” have been kept out of the draft Bill’s domain, and it would thus imply that such parents face no incentive or disincentive for not having or having more than two children. Strangely, for a Bill that seeks to promote population control, the language of the Bill has no specific provision for married couples or even unmarried persons without any children to claim any benefit.

It is safe to say that the draft Bill is rife with arbitrariness, as there is no discernible reason for the heteronormative and marriage-centric style of drafting, besides its fixation with incentivizing sterilization. In this context, it is relevant to point out that the rights of children born out of wedlock vis-a-vis the state are no longer res integra or undecided; they have been held eligible to apply for compassionate appointment and family pension on the death of government employees, apart from a right to inherit from their parents.

The law on arbitrariness in legislation has been crystallized by various judgments of the Supreme Court and the High Courts. In the Triple Talaq case (Shayara Bano v. Union of India 2017), the Supreme Court elucidated on the principle and defined the phrase “manifest arbitrariness” as “something done by the legislature capriciously, irrationally and/or without adequate determining principle”. The provisions of the draft bill clearly appear to be arbitrary and open to be assailed on this ground alone.

A Draft that is Not in Line with Recent Court Judgments

The draft Bill, it thus appears, has conflated the issues of controlling the population with a moralistic understanding of how citizens should plan their lives, in as much as they have to legally get married and have at least one child before they become eligible to claim any benefits. The law on the status of live-in relations has seen progress in the country, and various judicial pronouncements have granted greater protection to such relationships. Recently equating a woman in marriage to one in a live-in relationship, in the case of Lalita Toppo vs. State of Jharkhand and another, a three-judge bench of the Supreme Court observed:

“…under the provisions of the DVC Act, 2005 the victim i.e. estranged wife or live-in-partner would be entitled to more relief than what is contemplated under Section 125 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, namely, to a shared household also.”

Also, besides the intrusive nature of the mandatory sterilization procedure, such provisions themselves are also clearly invasive to people’s personal lives. Prescriptively monitoring the personal life of citizens falls afoul of the right to privacy. This was seen in the much-celebrated Navtej Singh Johar v. Union of India 2018 case, where the Supreme Court held that individuals have the right to union, which is part of the right to privacy, and that unions “also means companionship in every sense of the word, be it physical, mental, sexual or emotional.” It is hence suspect whether an insistence on undergoing a sterilization operation to achieve the objective of birth control can stand the stringent test of Right to Privacy laid down by the Courts. And, as far as sexual and reproductive rights go, the law recently also took a step forward with a recent amendment to the law on Medical Termination of Pregnancy by allowing for termination of pregnancy in case of failure of contraceptive method or device by an unmarried woman, which previously was only limited to married couples.

All in all, the legal understanding of relationships in India is seeing a tectonic change, that this draft Bill does not take into account. Recently, the Madras High Court has allowed for the registration of marriage between a man and a trans-woman under the Hindu Marriage Act. It is also important to note that although same-sex marriages have not been legalized yet, petitions seeking the same are pending before various High Courts awaiting judicial consideration. If translated into a piece of the statute, standing the test of judicial scrutiny would be a rather interesting challenge for the drafters of Uttar Pradesh’s population control bill.

The Real Need of the Hour

In his 2001 paper on population policies, Amartya Sen articulates that the way forward for population control policies is to consider multiple diverse influences on fertility; at the core of this is freedom and justice, not coercion and intimidation. Converging with Sen’s take on the point of awareness and agency, the Population Foundation of India (2021), while calling on states to “repeal the two-child norm”, recommends that states “spend more on healthcare, promote sexual and reproductive health services, invest in skills education, and create enabling livelihood”.

Besides these, PFI recommends that states see that girls complete schooling, improve the quality of and access to family planning services, introduce comprehensive reproductive sexual health education, invest in gender equality initiatives and advocate for male involvement and male responsibility for family planning. A particular impetus on education will result in “delayed ages of getting married, an increase in the marriage-to-first-pregnancy interval, and multiplier effects on the health of children”.

Also Read: Imagining a Two-Child Nation: Regressive Policy or Prudent Planning?

Thus, family planning departments in state governments need to incorporate population control policies that are crafted with a rights-based approach, focusing on reproductive self-determination, if such policies are truly to be impactful in the long term. Legislations like the Uttar Pradesh Population (Control, Stabilisation and Welfare) Bill, 2021, even in the form of a draft, ought to reflect the social dynamics of the times they are to be enforced.

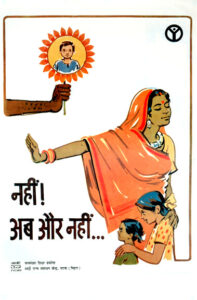

Representation featured image from the “hum do humare do” family planning campaign led by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi.