COVID-19 is a global tragedy. However, what is of greater concern is that the pandemic is merely a symptom of a much larger problem: climate change. In November 2019, just as the first cases were emerging in Wuhan, the National Geographic published an ominously prescient warning that beyond ecological destruction, deforestation also leaves us vulnerable to novel zoonotic viruses as displaced disease-carrying species are forced into contact with humans.

India is especially vulnerable to the effects of climate change, given our levels of population, poverty and inequality. According to a 2018 research study, India emits 6 percent of global CO2 emissions, but is estimated to suffer 20 percent of the global economic burden.

In the face of this looming disaster, the world needs to adopt a more ambitious, sustainable and resilient approach to mitigating climate change. A critical feature of our climate change response has to involve investment in and mainstreaming of nature-based solutions.

But what exactly does this mean? For far too long, restoration and preservation of natural resources like forests have been overlooked by our governments and the social sector alike in their climate response, despite its arguably unmatched potential. India’s development sector can help find and scale innovative models and interventions that harness the power of forests to mitigate the impacts of climate change at scale.

Forests are the overlooked climate change solution

Forests are one of the world’s best carbon storage powerhouses. While absorption capacity varies depending on the type of forest, research shows that adding nearly 1 billion hectares of forest could remove two-thirds of the roughly 300 gigatons of carbon humans have added to the atmosphere since the industrial revolution. For perspective, we have ~1.8 billion hectares of potential forest land globally i.e. areas of sparse vegetation or degraded bare soils.

Forests also provide a range of other ecosystem benefits including improved soil health and conservation, groundwater recharge, increased biodiversity, flood control, livelihood support and overall climate regulation. So much so, that one would assume that by now, forests are a mainstream solution to fight climate change. Unfortunately, this isn’t the reality reflected on the ground.

The data is dismal. Since 2014, deforestation rates have increased by 43% globally. The world is now losing an average of 26 million hectares of forests each year, an area equivalent to the size of the UK.

You May Also Like: Dhaval Negandhi on Siting Renewable Energy Projects Sustainably

India is no different. For decades, the Indian government has been struggling to reach its own target of bringing 33 percent of India’s geographical area under forest cover, as recommended under the National Forest Policy of 1988. India’s forest cover has been meandering around the 21% mark for well over a decade. While we can debate the scientific basis for this target and what the optimal forest coverage for India should be, the discrepancy nevertheless exhibits a lack of political will by successive governments to address the life and health of our forests in any meaningful way.

The National Forest Policy and 1980 Forest Conservation Act mandate compensatory afforestation in the event of deforestation. Not only is this a smokescreen behind which massive deforestation is carried out, but afforestation efforts are often unscientific, monoculture plantations with poor implementation, and scanty data on tree health and survival rates.

To add insult to injury, we have also been replacing our dense and biodiverse forests with young and ineffective forests that are potentially ecologically harmful. A case in point is the massive compensatory afforestation spree undertaken by the KIOCL after they strip-mined virgin rainforests in the heart of Karnataka’s Kudremukh National Park between 1980 and 2005.

Enabling forestry innovation

Forests have traditionally been relegated to the responsibility of the state. Hence, the philanthropic and private sector have had a largely hands-off approach towards this sector. This has resulted in a lack of innovation, financing, and a paucity of on-the-ground forestry program implementers.

In India, more than 75 percent of forest land is not classified as government-protected — areas like national parks and wildlife sanctuaries are particularly vulnerable to deforestation. The country also faces a severe land degradation problem, with an estimated 29 percent of land considered degraded.

This, despite the fact that advances in satellite and GIS monitoring technology have made it fairly straightforward to get accurate measurements on forestry outcomes like forest cover changes, carbon sequestered, tree health and soil quality. This provides a real opportunity for private and social sectors to finally engage with this space in an impactful and accountable way.

One approach to afforestation and forest protection that is rapidly gaining momentum is Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES). Under PES schemes, managers of land or other natural resources are financially compensated, conditional on their provisions of environmental services, such as water purification, landslide prevention, or carbon sequestration. It is essentially a conditional cash transfer. While the core idea is simple, the thought of placing a monetary value on ‘ecosystem services’ might be counterintuitive to many. So, let’s unpack it a bit more.

Why are cattle farmers in Brazil setting fire to parts of the Amazon rainforest? It is because they have a financial incentive to do so. This way, farmers have more land as pasture for raising cattle to meet the global demand for beef. And why are locals in the Raigad district of Maharashtra clearing their forest land? For selling the soil and sand underneath to highway expansion projects. Albeit a one-time sale and a modest sum of money, most locals still find it to be more profitable than keeping their forest land intact for years on end. These players have little economic incentive to provide environmental services.

This is a market failure that PES can address. Because PES is a market-based instrument, similar to an environmental tax or subsidy, it drives a set of environmental outcomes by placing a financial value on them. This is important given the inability of current markets to reflect the value of environmental ‘services’ such as carbon sequestration, water, and productive soil that the Amazon and other rainforests provide.

The inability of markets to peg the value of these goods and services and the failure of governments to adequately protect these forests has resulted in inefficient decisions for both the economy and the environment. A research study found that the annual expenditure on containing future pandemics by fighting deforestation, clamping down on wildlife trade and monitoring the vaccination of domesticated animals (costing ~$20 billion to $30 billion) would be minimal in comparison to the costs (~$11.5 trillion in the case of COVID-19) incurred when we are hit by one.

While there is some evidence that shows PES can lead to a modest reduction in deforestation, we need more rigorous empirical studies to quantify this further. One such randomized controlled trial study conducted in rural Uganda found that forest-owning households that received cash transfers conditional on them conserving their forests had a significantly lower deforestation rate compared to a control group.

What we’re doing at Farmers for Forests

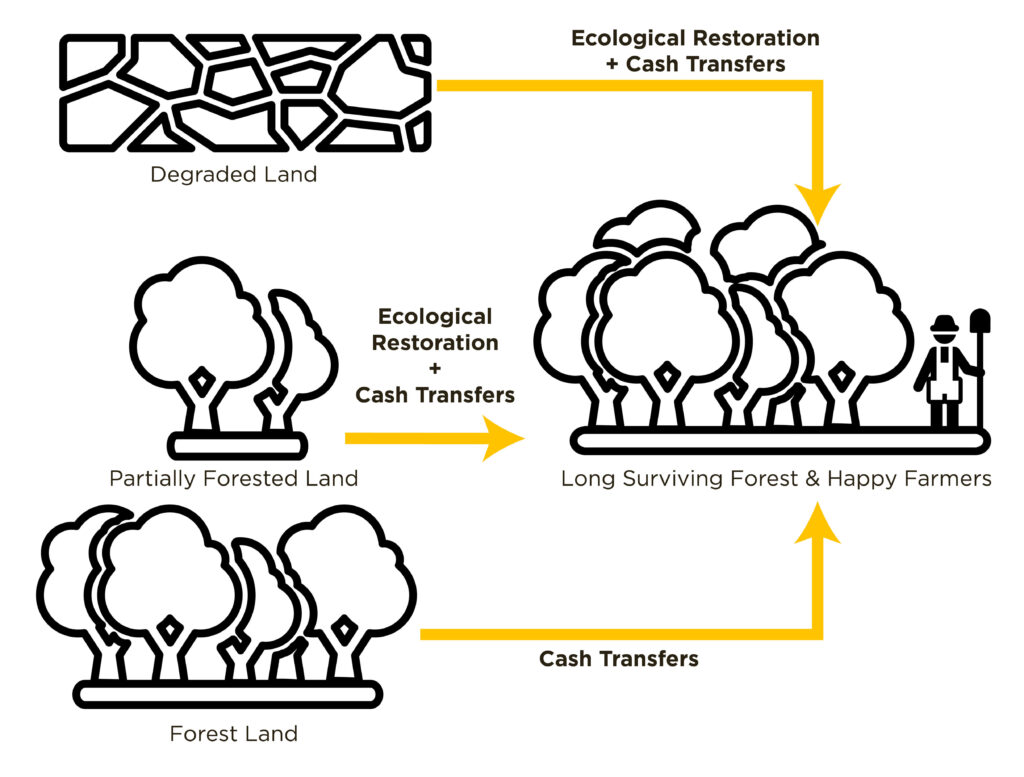

Farmers for Forests (F4F) uses the Payment for Ecosystem Services model to implement both afforestation and forest protection projects in India. F4F provides farmers and rural landowners quarterly conditional cash transfers (CCT) to either grow new biodiverse forests on their degraded or unusable land or protect existing forests on lands that are vulnerable to deforestation. The beneficiaries’ progress is measured quarterly using GIS and satellite mapping.

In our first year of operations, we are growing five acres of new native and biodiverse forests in Ahmednagar District, and protecting fifty acres of standing forests in Raigad District of Maharashtra.

The long-term vision of F4F is to not only come up with an accountable, scalable, and sustainable afforestation and forest protection model, but also to develop a robust forest cover and health monitoring platform. In an effort to overcome the scarcity of empirical studies that assess the feasibility of PES programs, especially within the Indian context, F4F also aims to conduct rigorous research on the impact and cost-efficiency of their programs in order to contribute to the global PES evidence base.

The potential for long-term positive environmental impact is, of course, promising. As one of the F4F beneficiaries Suresh Shinde, a farmer in Dhavalgaon with 4 acres of land on which he grows sorghum (jowar), onions and sugarcane points out:

Long-term environmental restoration programs are essential for ensuring the future of our village. Misuse of fertilizers and destruction of trees has led to decreasing agricultural yield and land degradation. It is important to try different things to restore our environment

However, there are also many unanswered questions, such as what the optimal economic valuation of an ecosystem service should be, or how many years beneficiaries ought to receive cash transfers for their pro-environment behaviours to be sustainable.

“You are giving us money for five years. What happens after that?” asks Machindra Subhana Dongre, a farmer in Dhavalgaon.

Time to bring nature back

For far too long we have prioritized economic development over environmental protections. However, this ‘economy vs. environment’ narrative has always been, at its core, a false dichotomy. It would be a gross oversight to assume that we are not paying a financial price for our CO2 emissions, cities becoming uninhabitable, record occurrences of cyclones, or the reduction in agricultural yield? A Stanford research study estimates that global warming has caused the Indian economy to be 31% smaller than it would otherwise have been.

As we try to claw ourselves out of COVID-19, we need radical reforms to solve climate change, including a paradigm shift in how we view environmental conservation.

Nature is often perceived as a victim of climate change rather than a powerful solution. Its restoration is often perceived as a fluffy philanthropic act undertaken sporadically, rather than the outcomes-focused and technology-backed solution it actually is. A forest-based climate solution is not as simple as just planting trees. It requires monitoring and accounting, operational efficiency, scalability, long-term sustainability, and of course, financing. While the state struggles to catch up, it bodes well for India’s private and development sectors to look beyond renewable energy start-ups and prioritize new solutions that mend humanity’s dysfunctional relationship with nature.

Featured image courtesy Farmers for Forests | Views expressed are personal

Sir,I am a farmer near chennai,I have 100 acres of farming..how do I earn through carbon credits…

I’m curious to know about the project. I retired as Director of Agriculture , Maharashtra state and am now on the Board of Directors of IndusInd bank as an independent directors

[…] You May Also Like: What if We Could Pay Farmers to Grow and Protect Forests? […]

Hello,

Can I associate with F4F and pitch in efforts to preserve environment.

Farm land available for afforestation in Amravati district.

Land available for plantation in

Vill. Barhali

Block.mukhed

District.nanded

Cantact.9075986151

FREE CALL ME IF U R INTRESTED

Sir mazi 4 acre jamin ahe barhali gavat.

Mi mazi jamin Jhade lavnya sathi deuichhito