Earlier this July, the 750- megawatt Rewa solar power plant was inaugurated in Madhya Pradesh. One of the largest single-site solar power plants in India, it is touted to drastically reduce the country’s carbon emissions, equivalent to 15 lakh tonne of carbon dioxide annually.

Glimpses from the solar power project that was inaugurated in Rewa, Madhya Pradesh, this morning. pic.twitter.com/uZOZ0YXxAQ

— Narendra Modi (@narendramodi) July 10, 2020

But “investments worth around ₹13 trillion have been affected due to land conflicts arising out of social and ecological factors in India across various infrastructure projects,” Dhaval Negandhi tells me over email, citing a recent report. Dhaval is an Ecological Economist with The Nature Conservancy – India; his job is to help the expansion of Renewable Energy (RE) in India while ensuring that minimal damage done to people and local ecology in the process. He does so with the help of a decision-making support tool called “SiteRight” which has been developed in partnership with the Vasudha Foundation, the Center for Study of Science, Technology and Policy, and the Foundation for Ecological Security. SiteRight is set to be officially launched in September this year.

I caught up with Dhaval Negandhi (DN) to talk about the tool’s ability to identify socio-environmental risks to proposed and existing sites, its data collection methodology, and the current challenges their team faces.

Vaishnavi Rathore (VR): As India pushes rapidly towards producing more Renewable Energy (RE), what kind of land conflicts occur?

DN: India is a leader in RE and is rapidly expanding its capacity. Set to cross the 100GW mark this year, most of this capacity is expected to come via utility-scale [large scale] wind and solar projects. However, land conflicts can play a spoiler in this journey because these projects require large areas of land for development.

Such conflicts are already emerging for us to see. For example, wind projects and associated transmission lines in Gujarat have been one of the major factors responsible for the recent deaths of the Great Indian Bustard, a critically endangered bird with an estimated population of less than 200 in India. In response, the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy has suggested retrofitting transmission lines, which increases the project costs.

Another solar energy project in Oran, Rajasthan threatens local communities’ access to grazing lands which are the only source of fodder for their camels and sheep. They also constitute one of the oldest Sacred Groves in India.

This is one of largest Sacred Grove (Oran) of Jaisalmer, more than 600 yrs old, highly worshiped by locals in the name of Shree Degray Oran. Also wintering ground of #GIB, now under threat from Solar Energy project. Locals fighting to save it, submitted plea to Collector. Save it pic.twitter.com/uKZieE1GWH

— The ERDS Foundation (@and_ecology) June 13, 2020

Such conflicts are likely to increase in the future as options for siting become more limited.

VR: Broadly, what are the implications of such conflicts?

DN: These conflicts have a significant economic cost too. In India, it is estimated that investments worth ₹13 trillion have been affected due to land conflicts that arise out of social and ecological factors across various infrastructure projects. In a survey released earlier in July, the CEOs of RE companies in India ranked land acquisition as the top challenge for their sector.

COVID-19, and the induced reverse migration has further exacerbated the risk of social conflicts; displaced migrants returning to rural areas has increased villagers’ dependence on land for subsistence and livelihoods. If this pressure on local resources isn’t managed proactively, land and water conflicts will raise risks for the RE sector and those financing it. Be it because of project delays, higher costs, or rising negative perceptions about the sector, such conflicts will ultimately slow India’s much-needed energy transition.

VR: How does the SiteRight tool aim to help solve this problem?

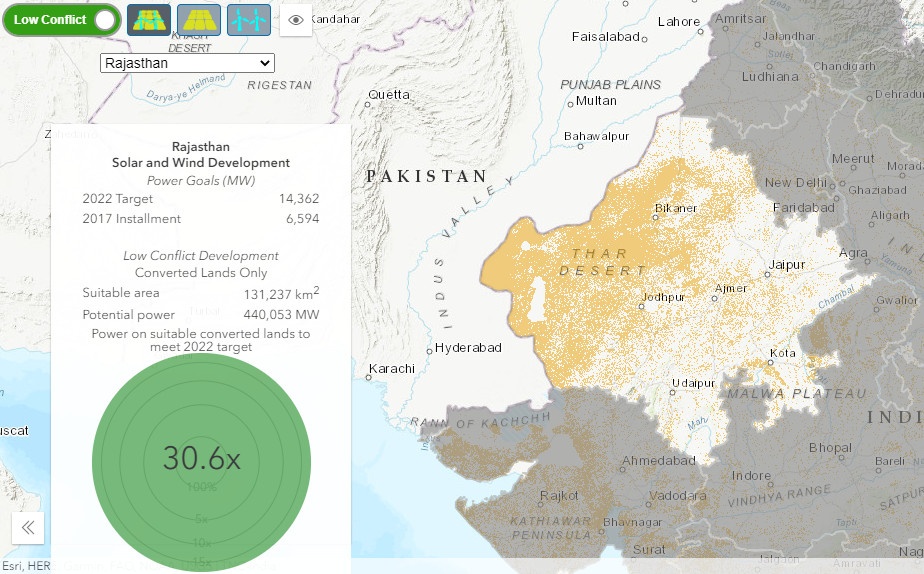

DN: The good news in terms of emerging conflicts due to large renewable projects is that if we take steps today to guide the growth of renewables to areas with lower ecological impact, we can develop more than enough RE–greater than 10 times our 2022 capacity goal. In that context, these partners have collaborated to reduce socio-environmental risks for the RE sector.

SiteRight aims to facilitate the rapid expansion of RE while ensuring minimal harm to places important for nature and people through lower impact siting. It can be used by policymakers, businesses, and financial institutions to not just identify socio-environmental risks to sites already identified for RE projects, but to also identify alternate sites for projects with viable solar and wind energy potential but lower socio-environmental impacts.

It is also very encouraging that the World Economic Forum too has recognized the need to site renewable energy projects smartly to support the health of critical ecosystems. In a report released last week, the SiteRight tool has been featured as one of the ways to enable a nature-positive energy transition.

VR: Recently, we also saw Adani Group bagging a USD 6 Billion solar deal, touted as the world’s largest solar project. As the private sector also steps into renewable energy projects, what significance do you think the tool holds?

DN: Decentralised solutions, such as rooftop solar apparatuses, have several socioeconomic and financial advantages apart from being less susceptible to land conflicts and should be encouraged. However, it is fair to say that large renewable energy projects are likely to contribute the largest share of our RE capacity in the foreseeable future. Thus, siting these large projects in lower impact areas is clearly critical.

At large, the tool demonstrates that better and proactive siting approaches do not require a compromise on our RE goals. We only need to approach this in a proactive and coordinated fashion so that impacts on biodiversity and on people dependent on natural ecosystems are minimized. And by doing that, we are also reducing conflicts and risks for the RE sector, thereby expediting deployment.

SiteRight can support policymakers by allowing India to accomplish the 2022 and 2030 goals [175 GW of renewable capacity by the year 2022, and 450 GW by 2030] with reduced risk for the RE sector. Further, it can improve the ease of doing business (by minimizing the risk of conflicts that affect project timelines and investments). The tool can also enable a coordinated approach which ensures that other policy goals (such as sustainable development goals, reforestation goals in our NDC commitment to UNFCCC, tribal development, land degradation neutrality, and others) are not compromised in our effort to advance RE.

Developing & financing solar #energy projects is key to mobilizing investments for #ClimateAction & reach the goals of #ParisAgreement. The #CS75 side event hosted by #India, #France, @isolaralliance & ESCAP reviewed how stronger int’l cooperation is vital to achieve these goals pic.twitter.com/lnWcXLIC2H

— United Nations ESCAP (@UNESCAP) May 28, 2019

Similarly, for developers and businesses, SiteRight can help reduce project costs and delays by avoiding and minimizing the risk of socio-ecological conflicts.

Finally, SiteRight supports investors and institutions who finance RE projects. It does so by reducing unforeseen risks to their investment, minimizing the extent of land-conflict induced stranded assets, improving their financial and operational performance, alongside helping them operationalize their environmental and social safeguards or due-diligence processes.

VR: How is the data for SiteRight collected?

DN: The tool uses environmental data collected by national government agencies such as the Wildlife Institute of India, the Survey of India, and the Indian Space Research Organisation, among others. It also includes data disseminated by other reputed international agencies such as BirdLife International on Important Bird Area and Key Biodiversity Areas. We have also used habitat data for threatened and endangered species based on data collected and distributed by the IUCN. For social data, we have compiled village-level information from the 2011 Census of India.

In its current version, SiteRight does not include any primary data. At present, the tool is active in Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra. However, in our plan to include all the other states, we are also considering enabling a two-way flow of information. So, while the current version only helps users to get results from the tool, we are aiming to ensure that the next version enables local communities and other civil society organizations to improve the underlying data by contributing missing information. This will also benefit users of the tool who’ll have access to richer and more extensive data, while mitigating limitations with respect to spatial data, which is a major challenge in India.

I also want to emphasise that SiteRight should be one of the sources of information considered for siting-related decisions before any significant investments are undertaken. It is not intended to replace the need to conduct detailed site-level impact analyses or the importance of consulting relevant impact-assessment agencies before making siting decisions. These are, after all, complementary to the objective of SiteRight and have their own significance.

VR: Often, advocating for ecological impacts with the government is seen to be challenging. How has the experience been for you and your team with the tool?

DN: I feel that government departments are more likely to engage meaningfully if you go with a solution to the problem that they are already facing. Land conflicts are increasingly becoming a major challenge for the RE sector, and hence identifying ways to mitigate such conflicts can accelerate India’s growth towards its RE target. At the same time, it is in any government’s interest to minimise socio-environmental damages; many departments understand how it can help them implement their policies better.

We have been engaging with several government departments while developing the tool and have also demonstrated its functioning to a few of them. This includes the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE), Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, as well as energy departments at the state level in Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra. Here, I must say that the response has been encouraging.

For example, a 2013 report commissioned by the MNRE identified the need for an RE zoning exercise which would consider the ecological and social sensitivities in addition to the RE potential for a project. SiteRight helps operationalize the Ministry’s recommendation, and the Ministry has indicated that it will consider the tool for usage.

For smarter siting, we need to shift from a piecemeal approach of planning projects to an integrated approach that helps us achieve our RE goals while considering which lands to develop these projects on. The SiteRight tool has been designed to support governments at the state and central level in making this paradigm shift.

VR: As the tool is still being developed, what major challenges do The Nature Conservancy and the other partners currently face?

DN: As we continue to demonstrate the tool to our target audiences, we have received several suggestions on additional datasets that can be added to increase its utility. The preliminary constraint for most of these datasets is the availability of data. Across government entities, the quality and consistency of spatial data (for example, the current land use) is a major challenge for a tool like ours. Providing additional data that will improve our target audience’s decision-making capabilities is our primary challenge.

Ultimately, the SiteRight tool is as good as the data which underlines it. Updating the datasets so that they are reliable and adequately reflect the status quo is also our top priority. This way, the tool can continue to help inform policymakers, governments, businesses, and financial institutions.

Featured image courtesy of (L) Andreas Gücklhorn on Unsplash, (R) Dhaval Negandhi. | Views expressed are personal.

[…] You May Also Like: Dhaval Negandhi on Siting Renewable Energy Projects Sustainably […]

[…] land acquisition for solar parks in India remains embroiled in community opposition–the anti-democratic amendments to the draft […]

[…] that has over 300 GW potential of wind energy, a boost in this sector while ensuring minimal socio-environmental impacts during its expansion could contribute to a greener future. As we move into the […]

[…] Also Read: Dhaval Negandhi on Siting Renewable Energy Projects Sustainably […]

[…] land acquisition for solar parks in India remains embroiled in community opposition–the anti-democratic amendments to the draft […]