Written by Avantika Bunga, Gopika Kumaran & Shreyasi Rao

The Indian State’s fraught history of ensuring primary education for marginalized communities has made madrasas viable substitutes for government schools in many localities. At 68 per cent, the 150 million Muslims living in India present a much lower literacy rate when compared to the country average of 74 per cent. And while their population across states may vary, some like Haryana have rates as low as 53 per cent.

Especially for Muslim communities living in poor urban areas, madrasas are the only option for a child’s education. Ever since the inception of the system around the 11th century AD, Madrasas have retained their original raison d’être of staying true to religious education. Back in 2015, the Maharashtra government derecognised madrasas which do not teach modern subjects, calling them “non-schools”. Although Vinod Tawde, the Minister for Education in the state, insisted that adding subjects like Math and Science would improve learning outcomes, the de-recognition of madrasas caused an outburst of dissent from the Muslim community.

The National Democratic Alliance secured 353 seats in a 17th Lok Sabha that only has 27 Muslim members, none of whom belong to the BJP. In his first public address since the verdict, Narendra Modi promised a future of inclusionary development, especially for Indian Muslims. That this venerable call carries the baggage of years of communal incitement, any government intervention into the functioning of madrasas requires a nuanced negotiation of the status quo.

Situating the Madrasa

A derivative of the Arabic word ‘darasa’, ‘madrasa’ refers to a centre of education. The system in India is divided along the Deobandi and the Barelvi sects, which determine the syllabi taught. This generally includes subjects such as Urdu, Koranic studies, arithmetic and Arabic and Greek sciences. Dr Zafarul Islam Khan, the chairman of the Delhi Minority Commission, tells us that “madrasas are preferred by poor parents because they do not charge tuition, food and lodging fees.” The anganwadis in some Muslim-majority areas are reportedly worse alternatives to madrasas and finding an all-girls school run by female teachers is rare for parents.

Of late, there has been a renewed interest in madrasas as emblematic of a safe space that can stem the systemic erasure of Islamic culture amidst a movement to saffronise mainstream schooling. This notion of privately guarding Islamic teachings from neocolonial processes has catalysed resistance against calls for reforming the madrasa system. Asaduddin Owaisi, President of the All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen party has said that “no subject can be imposed on madrasas” in response to the Maharashtra government’s measures in 2015. “He [Owaisi] tells me there is no need for change…that the system has been traditionally run and it will continue to do so. Most Muslim politicians do not want reform”, laments Mr Arshad Shaik, the President of Today’s Kalam Foundation.

Some states have ‘Madrasa Boards’ that oversee their functioning and see that the curriculum is at par with the matriculation syllabus. Clerics like Maulana Salman Nadvi have called these boards “a tool to damage the religious educational system.” As Dr Khan says, “The Centre wanted to introduce a central madrasa board which interested madrasas would be affiliated with. Their degrees could then be recognised by the state…the scheme was shelved because larger madrasas were opposed to it.”

While few receive occasional help from state governments, the madrasa education system faces funding challenges because most schools subsist on private sponsorships and donations. Mr Shaik’s main complaint is with management that stubbornly resist government help. “If they take funding from the government, then the maulanas fear that [the government] will change the religious curriculum that is traditionally being taught.”

Instead, as Dr Khan tells us, “Madrasas are funded by the community, especially through Zakat (poor-due) which is compulsory for every rich Muslim”. Yet, across the country, madrasas constantly face a resource crunch and struggle to provide sufficient infrastructure, teachers, and teaching equipment. When asked if private funding would get affected if madrasas change their syllabus, Dr Khan replied, “Donors are usually not bothered about what is taught. A donation is a form of religious duty in the interest of promoting religious education.”

Reform Ebbs and Flows at the Seams

Madrasas’ traditional mode of education has isolated students from mainstream occupations and higher education opportunities. Not all who graduate can be absorbed into mosques and other religious professions, leaving them with little choice in competitive job markets.

An NSSO survey found that Muslims are the poorest religious group in the country, with a per capita spending of Rs. 32.66, compared to the 37.50 for Hindus and 51.43 for Christians. Some marginalized Muslim communities have voiced the need for reform. A recent survey in Mewat reported that 70% of the households with children attending madrasas favoured a change in syllabus and recognised the importance of proper English education and scientific knowledge.

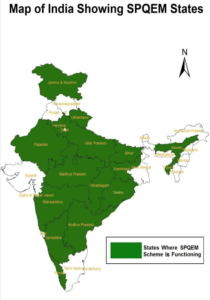

The HRD Ministry’s Scheme for Providing Quality Education in Madrasas (SPQEM) scheme facilitates madrasa affiliation with recognised boards like the CBSE, State Boards and the National Institute of Open Schooling (NIOS). The first structured scheme to “modernise” madrasas was the Area Intensive Madrasa Modernization Programme in 1994, followed up by the currently active SPQEM. Started with aplomb in 2009, the program came with high expectations. According to a 2013 evaluation report, although most stakeholders unanimously agree that the scheme has had an overall positive impact, actual implementation left much to be desired. Intervention is mostly at the elementary education level, and many madrasa officials weren’t aware of the assistance provided for NIOS accreditation in the higher levels.

The SPQEM lacked a specific curriculum to integrate formal subjects. Madrasas were asked to blindly follow the state curriculum, over 20,000 teachers appointed in Uttar Pradesh received irregular salaries and schools suffered from badly maintained computer equipment. The same issues appeared in the 2018 evaluation report, indicating that the lessons weren’t easily learnt. However, the scheme has been extended up to 2019-2020, with new revisions.

According to Maneesh Garg, the joint secretary at the HRD Ministry, “Affiliation to any board will help the students passing out of these madarsas to progress to higher levels of education when they complete their schooling.” Apart from these, certain universities like Jamia Milia Islamia and Aligarh Muslim University offer ‘bridge’ courses that focus on English skills, social sciences and computer literacy. Today, only degrees issued by recognised madrasas are considered equivalent to CBSE certifications in West Bengal, Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, Chhattisgarh and Uttar Pradesh. Students with ‘Fazil’ and ‘Alim’ — degrees conferred by madrasas — are eligible for B.A. and M.A programs in Arabic, Islamic Studies and Theology.

Looking Ahead

In the wake of the Assembly elections, the government must be cautious not to threaten the religious freedom of madrasas. ‘Modernisation’ cannot be served in a one-size-fits-all plate. In several parts of the country, it is prudent for children to attend conventional schools during the day and madrasas before or after school. Overall, the largest hurdle faced by state-led initiatives is the callous implementation and operationalisation of reform. Formal subjects can only be integrated in a way that complements existing religious pedagogy, trains teachers and acquires funds for infrastructure and affiliation.

As Today’s Kalam Foundation’s work has shown, autonomous institutions must lead the movement for reform in madrasas. Since the institution itself has great penetration and holds cultural importance for Indian Muslims, it is an already established route to educating economically backwards Muslims and other minorities. Regularised and adequate funds must find their way to reach approximately 40,000 madrasas in the country and ensure that the students have a fair chance to secure jobs later on. Modernising madrasas has already increased enrolment rates across the country. If reformed, they have the potential to improve literacy rates amongst one of the most neglected communities in India. After all, access to quality education has to be the first step in realising an inclusive ethos of development in the future.

Featured image courtesy Today’s Kalam Foundation

[…] You May Also Like: Situating the Madrasa in Modern India: Is Reform Around the Corner? […]

Ajuda a expelir rugas, bigode chinês e marcas de sentença. https://www.mrandmisswestindiesuk.com/index.php?action=profile;u=199072

Montão: Grupo dentre Danças Folclóricas Alemãs Edelweiss.

Banda etária dos quadro da aptidão.