Co-authored by Shraddha Tripathi & P. Charith Reddy

A 2017 WHO report revealed that the current doctor-population ratio of India to be 0.62:1000 as against its prescribed 1:1000 standards. What this means is that while the recommended doctor-to-population rate is one for every thousand, India’s rate is a depressing 0.62 per thousand. There are a mere 8.18 lakh doctors for active service, serving a massive population of 1.33 billion people. Thus, there is no question that we need more doctors.

At the same time, given how complex and specialized the field of medicine is, quality must not be compromised to meet quantity requirements.

The Supreme Court’s landmark judgement on April 2016, declared the National Eligibility cum Entrance Test (NEET) as the only exam to be conducted for securing seats in all public and private medical colleges. Although this was put in motion with the hope that it would ensure a strict and transparent process, NEET turns out to be fraught with loopholes.

Quality and Quantity Must go Hand in Hand

In order to meet the prescribed WHO standards, there has been a significant drop in the cut-off marks in NEET, with a simultaneous increase in the number of seats for an MBBS course. An analysis of the recent data released by CBSE shows precisely this.

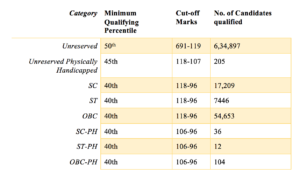

NEET 2018 Cut-offs

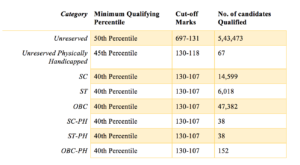

NEET 2017 Cut-offs

This year, candidates falling within the 50th percentile in the general category were declared as qualified to pursue an MBBS course. This meant students securing as high as 691 and as low as 119 out of a total of 720 marks were considered eligible. For those in the reserved categories, the required percentile was further dropped to 40, which meant that 96 were the minimum qualifying marks. As opposed to this, cutoffs for the 2017 NEET exam were at 131 for the general category and 107 for the reserved category.

The situation in private colleges is quite shocking, as students with less than 25th percentile have been taken in for MBBS courses.

As per a TOI report, students who got 5% in physics, less than 10% in chemistry, and 20% in biology, and still made it through!

Thus, the system which was initially supposed to keep non-meritorious students out has not been able to accomplish it. For all categories except ST, even a percentile of 88 would have ensured enough and more qualified students to fill seats in medical colleges of Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Uttar Pradesh, Assam and Kerala. For the ST category, the same rule would apply at the 75th percentile.

Exorbitant fees have also added to the poor standards of medical colleges; students from affluent families with poor scores buy seats through exceptionally high donation amounts. On the other hand, candidates with a relatively high score, higher on the merit list, and from a worse off socio-economic background, are forced to drop the idea to study medicine on account of enormous fees. While merit should ideally have been the criteria for admitting students, monetary status gains precedence and quality is kept at bay.

In Punjab private medical institutions charged as high as 64 lakhs, against 4 lakhs in government colleges. In UP alone, over 2900 students out of a total of 4908 were below the cut-off marks; several who made the cut-off could not afford to pay the fees for these colleges. Many seats in Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Punjab and Haryana remain vacant due to the same reason.

Dealing with the Conundrum

The state has intervened to try and regulate the ever-spiralling fees of medical institutions. For instance, in early June, the Madras High Court fixed fees at Rs. 13 lakhs per annum, saying that the fee of Rs. 25-30 lakhs per annum was too high. This might ensure that more meritorious students with weaker monetary resources have the opportunity to get a seat, but this would by no means guarantee it.

There should be no compromise on the quality of students at all; students with a good grasp on the subjects essential to qualify should only be able to make it through the examination. In addition, an exit exam which is conducted with strict rules and regulations is a must for ensuring quality standards of medical practitioners within the country. This exam could be conducted by an independent third party, and would be made compulsory for both, private and public institutions; such a system might work to ensure that regardless of the marks a student entered college with, only those that pass a certain accepted threshold can go ahead. These could be vital steps to raise well-versed, knowledgeable and efficient medical practitioners.

Such steps might just aid in ensuring that quality is given, if not more, then the same kind of importance and attention as quality. The India of today has a long, long way to go before it can satisfy the needs of its populace; the healthcare system and NEET need to be tinkered around with much more, to ensure that the people are given the best, and nothing but the best.

Featured image courtesy Adam Jones|CC BY-SA 2.0