Written by Tanvi Mehta

While creating the education system for independent India, the first Education Minister, Maulana Azad, shouldered the responsibility of creating an institution that would not only uphold the national consciousness of the country but also define it. How the education system chose to disseminate knowledge would set a precedent for how the recipients of this knowledge - the citizens of the country - would view the world.

The National Education Policy of 1968 was a revolutionary document that drew upon nationalist ideas to create a liberal, secular education system that aimed to prioritise human development over economic capability. In other words, the NEP was designed to empower Indians to determine their national culture and the basis of its international presence.

While this spirit of learning was at the centre of the education system for the next two decades, the 1986 National Education Policy drastically reoriented its goals. Not only had the political climate transformed over the past twenty years (and was to change even further in 1991), K. N. Panikkar notes in Economic and Political Weekly that educators were increasingly concerned about creating citizens who were able to participate and gain prominence in the international economy. This materially focused, skill-based system — whose main objective was to capitalize on India’s growing youth demographic to get ahead in the ‘race for social and economic development’ — was further reorganized by the National Knowledge Commission (NKC) in 2005, he says.

Using development as a measure for familiarity with international standards, the NKC focused on three areas: centralization, for which the existing University Grants Commission was a channel; privatisation, facilitated by the public-private partnership guidelines of the Planning Commission; and foreign collaboration, aided by the Foreign Education Providers Bill of 2010.

So, by introducing a centrally controlled, western-influenced system, a neo-colonial structure was created. While literacy and enrolment rates may have been increasingly emphasized upon, education was not - learning was available largely to a growing privileged middle-class.

Enter Liberal Institutions

Today, many are of the opinion that India’s education system is in desperate need of an overhaul; the quality of learning remains sub-par in most institutions, while gross enrolment rate remains low at 25%. For those who do make it to university, opportunities provided focus primarily on the service sector – which is the fastest growing in the world - and often prioritise creating employable workers over learning. The Foreign Providers Bill has also met with limited success owing to stringent financial regulations and the bureaucratic obstacle course in the form of the UGC. Yet, the last National Policy was released in 1986 - and the current government has been unable to hold good to its promises of reform for three years now.

It is to address this difference in ideals – between thinking, politically active citizens and simple, economic units – that a new breed of philanthropy-driven private universities comes in that aim to provide a liberal, critical approach to knowledge-production. By looking within the country to shape perspectives and simultaneously fostering international collaboration, they seem to channel the voice of Maulana Azad, allowing for self-determination within learning. Azim Premji University, Flame University, Ashoka University, Auro University and the up and coming Krea University, are some such institutions.

This syncretic approach seems to be a refreshing change from the stifling single-mindedness of the prevalent education system. Education in these institutions promises to be more than just skills that can be sold; it has the potential to empower citizens socially, politically and economically.

Can They Stay True to Their Purpose?

But can such a system survive in its original purpose when free speech, the founding principal of a liberal education, is a murky topic in the country? The environment into which these private universities enter paint a bleak picture of how they might be received - textbooks are being rewritten, books banned, events attacked by mobs and students arrested.

Free speech has become a worryingly precarious issue and already, academia is protesting the situation they must work in (or around). Nationalism is held down by the opinions of those who have the power to impose it, and thus cannot be compatible with liberalism without creating friction. It is difficult, according to Santosh Kumar, a Professor of Liberal Arts at Auro University, for the environment in a country that lives in ‘several centuries and millennia simultaneously’, to surpass its many paradoxes and allow for liberal thinking. Its systems rely heavily on regulatory authorities like the UGC, creating a ‘semi-authority’ in which critical and independent thought cannot grow.

Already, private liberal universities are beginning to feel this tension; in 2016, Ashoka University faced controversy after a petition condemning India’s use of force in Kashmir was circulated and signed by staff members, who subsequently resigned after alleged internal pressure. The university’s statement distancing itself from the views expressed in the petition and its decision to moderate students’ emails raised further questions about the sanctity of free expression.

Students in other institutions have faced similar censorship. Simran Taneja, a student of FLAME University recalls:

On 1st January 2017, the Bhim Koregaon protests took place in Lavale village, close to FLAME. My colleague and I decided to collect testimonials from the residents in an attempt to understand the different narratives about the protests held by different caste communities. We submitted the article to The Context, a management-backed, student-run magazine. When they finally met with our editor in April (after having submitted it in March), the university’s senior manager for communications and marketing told her we were trying to cover one of the few issues they didn’t want us to. Finally, the article was not published.

Incidents like this raise serious concerns about the sustainability of liberal ideals within educational institutions.

Informed, critical and democratic citizenship necessitates the ability to independently examine concepts and processes, and make autonomous evaluations.

It is true that an education that emphasises critical thinking over skill-based learning is something that only a privileged few can even spend time on, but its presence in India means far more than simply an imposition of an ill-fitting system. Not only could the beginning of independent thought open avenues for an inter-disciplinary approach to be adopted across other public institutes of higher education, this could eventually percolate into school systems as well, thus allowing skill-based occupations to be taken on out of choice and not necessity.

Liberal arts institutions must not only allow for but also offer support to students who ask difficult questions in order to facilitate a national identity that truly encompasses the experience of the Indian citizen. Can Maulana Azad’s ideals be revived in a country that is notorious for its censorship? Philanthropy might buy students award-winning faculty and superior resources – but is the price of free speech too high to afford?

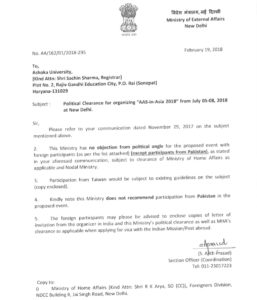

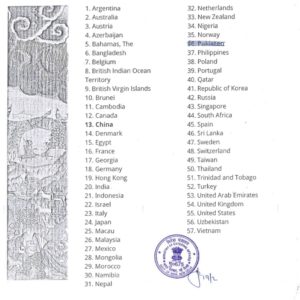

Perhaps it is too soon to answer these questions. But the precedent set by these initial encounters between university and government is a worrying one. For instance, Annie Zaman was the only Pakistani scholar attending the prestigious Association for Asian Studies-in-Asia conference, co-organised by Ashoka University in Delhi. She was told by the organisers that the Indian Embassy would most likely not sanction her visa, and hence she should not apply for one.

The survival of an institution relies on government support, or at least its non-objection. The Indian liberal arts college must maintain a precarious balance, then, between an academic culture of critical thinking and its own survival, without going against its founding ideals. A lot rides on the sustainability of an institution of its kind – it not only creates hope in a system held back by ideological stasis but might also open up avenues for the proliferation of a system of independent thought, not only in colleges but potentially in schools as well. Only time will tell how well it serves this purpose.

Disclaimer: A previous version of this article misquoted Simran Taneja. This has been corrected. The Bastion apologizes for the miscommunication.

Featured image courtesy Wikimedia|CC BY-SA 4.0