This is the last of our three-part series investigating the challenges faced by women studying STEM in Indian higher education. To get the full picture, read the first two stories that ask Where are the Missing Girls of our IITs? The Leaky Pipeline and Busting Myths Around the “Supernumerary” Seats.

It is difficult not to be overwhelmed by the gender imbalance at a typical top Indian science university classroom unless of course, you benefit from it. Take this for instance—IISER Pune’s BS/MS program has 1071 people enrolled, out of which only 285 are women; IISER Bhopal’s institute male-to-female gender ratio stands at 2:1. As the previous two stories in this series showed, this gender gap manifests most starkly in public engineering colleges of prestige, like the IITs, for example.

However, with their interdisciplinary curricula and relatively more holistic admission processes, modern liberal arts and sciences universities in India promised something to create different learning spaces that were inviting for women aspirants. However, systemic gender barriers go beyond the numbers game; women in the sciences are challenged more subtly in these universities—in the form of peer-to-peer and student-faculty interactions, non-inclusive pedagogy, and patronizing eye-rolls in classrooms.

The central case study of this story is the alma mater of the author, Ashoka University. Besides the obvious proximity, Ashoka University is interesting for another reason. Having launched its undergraduate program in 2014, it stands at an important juncture in its young journey: in September, Ashoka University announced the expansion of its science program into a new 27-acre campus, consequently growing its student intake.

With this news, its upcoming Trivedi Centre for Biosciences, and its new science PhD programs, the massive scale and potential of Ashoka University’s science program is just beginning to unfold. At this point, if the university can truly expand which students are celebrated in its science and research programs, it can help create a more inclusive science environment for several young minds in the country.

Okay, but what is a liberal arts and sciences university in the first place?

The most established examples of such universities are the Ivy League schools of the US, while Ashoka University and Krea University are two well-known examples in India. Unlike the leaky pipeline to the IITs, these universities’ admissions processes allow applicants to showcase their abilities and curiosities beyond exam scores. Admission processes here also assess the “merit” of an applicant by considering their socio-economic contexts. Coupled with need-based financial aid programs, there is a clear attempt by these universities to create diverse student bodies.

Modern liberal arts and sciences universities are fundamentally different from traditional STEM universities in India. With liberal arts, a student has to declare their major only after having explored a range of courses across disciplines in the first three semesters. The academic focus is on interdisciplinarity; as opposed to a ‘pure’ Physics major, one could also do a minor in a humanities subject like Philosophy. This fosters a culture of critically inspecting one’s own discipline, which is sometimes missing from the sciences.

What makes you think that women studying science here will have it better than other universities in the country?

It is well-documented that high-stakes exams put female candidates at a disadvantage. As compared to competitive exams like the Joint Entrance Examination (JEE), the holistic admission process in a liberal arts university can create a relatively more level playing field for women interested in studying science. Political discourse is also a significant part of a student’s life here, both inside and outside the classroom, as a result of which women are more willing to identify systemic sexist practices.

A healthy gender ratio (Ashoka University has had more women than men on campus since its inception) allows for less male-dominated campus culture, and better sexual harassment redressal mechanisms than those that exist at traditional universities, which remain heavily dominated by men. This gender ratio is not trivial: supernumerary seats were introduced in IITs to increase women’s representation in them to a mere 20%, and it has also been well documented that sexual harassment is a serious deterrent to women pursuing STEM. Rimjhim Gupta (Biology, ASP ‘21) also points out that Ashoka University’s smaller class sizes make it easier for her to speak up and be curious. All these factors together reduce the prevalence of blatant markers of sexism that otherwise plague higher education for women in STEM. In fact, all the women interviewed for this story were in agreement that universities like Ashoka are safe havens when compared to the status quo.

Also Read: Where are the Missing Girls of our IITs? The Leaky Pipeline

Having said that, there remains discernible class and caste privilege that the average woman studying in an Ashoka classroom possesses over their counterparts in public universities. This, in most cases, also translates into familial support and generational wealth that aid their career in STEM; it is well known that research careers in this field are notorious for demanding at least a decade of post-school education and a sizable amount of financial freedom, to begin with. Unfortunately, both of these are still luxuries for women in the country at large.

Okay, these liberal arts and sciences universities sound great. So, what’s the problem?

Here’s the paradox. Despite being a women-dominated campus, STEM disciplines at Ashoka University remain heavily dominated by men. For instance, in the undergraduate batch that graduates in 2022, at least 7 out of the 10 physics majors, and 37 out of 55 computer science majors are men.

A study based on a 2019 survey by Professors Aparajita Dasgupta and Anisha Sharma on the student body of Ashoka University titled ‘Preferences or expectations: Understanding the gender gap in major choice’ reveals that for the undergraduate cohort, only 15% of the female respondents reported a desire to select a science major, as compared to 25% of male respondents. This is despite the fact that out of the 351 respondents of the survey, 193 (55%) were female.

Of course, these numbers are not as abysmal as in the IITs because the haven does work to some extent. But the gender-in-science problem transcends this student body ratio.

Huh, what?

Here’s how the haven is not free from external gendered tropes. The main reflector of this is the following statistic: Ashoka University only has 6 professors who are not cis-men, out of over 40 professors across its STEM departments. Computer Science and Physics departments are composed entirely of male faculty members. Krea University has a similar, perhaps worse, faculty gender ratio.

The dearth of women faculty makes it difficult for women students to create informal bonds and network with their professors. Tanvi Roy (Computer Science, UG ‘22) encapsulates this succinctly. “My friends who are men get mentored because male professors always form a small group of male students in each class that they are comfortable being informal with. It is extremely rare to see that kind of a relationship between a woman/non-binary student and a male professor”. This impacts the kind of opportunities available to a woman studying science. Atharvi Bais (Computer Science, UG ‘22) builds on Tanvi’s point, saying that “Most of the time, a professor’s Teaching Assistants (TAs) and Research Assistants (RAs) are composed only of the small circle of male students that they have formed. Usually, there are no emails sent out for an RA-ship opening. We hear about them through our professors informally. Of course, the first ones and sometimes the only ones to hear about it are the men in a professor’s small circle.” Atharvi continues, “It’s not difficult to imagine how not having RAships and TAships affects your letter of recommendations for graduate school. However, the more profound effect is, perhaps, that missing these opportunities means being unable to explore the discipline in depth and chance upon what someone may actually want a career in.”

Besides this, the lack of mentors impacts women’s journeys in STEM in a more fundamental way. STEM disciplines are brutally difficult, especially during the transition from school to university. Professor Sharma and Dasgupta’s findings also reveal “science majors to be perceived as the most difficult, with only 55% of students predicting that they could score an above-median GPA, compared to 64% in economics, 74% in the social sciences, and 70% in the humanities”. Most students who end up sticking with a science major are people who found mentors, almost always in the form of professors, who could reassure them of their ability time and again. Rashmi Gottumukkala (Physics, ASP ‘21) shares, “It’s difficult to imagine how far I would have gotten if I did not have my professors and TAs telling me that struggling with the subject initially did not mean that I did not have it in me to become a good physicist. For most of us, failing is a rite of passage in science”.

Students who cannot harness such mentorship often end up convinced that their initial struggles signal their individual deficiencies. As Professors Dasgupta and Sharma find, they are less confident of their scores in science than men, even when accounting for ability. This, coupled with the fact that women value getting higher scores than men do when deciding a major means that the phase of scoring poorly in courses sways women farther away from science than it does to men. Esha Datanwala (English and Media Studies, UG ‘20) switched out of physics partly because this gendered system made her think that she was not good enough for a physics degree. In the absence of a mentor and after struggling in a math-heavy physics class, she switched to the humanities. Esha is now a two-time New York Academy of Sciences challenge winner, most recently for building a surveillance system for the Tracking Coronavirus Innovation Challenge in 2020.

Not seeing enough women role models in the form of professors leads to women self-selecting and switching out of STEM majors. Tanvi elaborates, “This happens especially when there are humanities and social science departments which have tremendously higher percentages of women faculty. It is easier for a woman to imagine [a future with growth] there”. Students’ beliefs about whether they will enjoy studying a particular subject, are likely to be deeply rooted in prevailing social norms; how much they enjoy a course greatly influences their choice of major, as Professor Dasgupta and Sharma find.

Atharvi suggests that this lack of women in faculty can be partly compensated by having more non-males as Teaching Assistants, especially for introductory courses, which is “where we lose most women”.

Male professors in STEM also tend to not understand the experiences and hesitations of their students who are not men themselves. Esha recounts her initial experience studying science. “I always felt discouraged to actively participate in class because the men in my physics class would just roll their eyes whenever I asked a question and the professor wouldn’t do anything,” she says. Rimjhim nods in agreement, “It is easier for men to mansplain when the class is dominated by men, and the professor is one too, because they do not understand that mansplaining is a problem in the first place.” When the only way of participating is speaking up in class, women invariably lose out. “A more flexible class participation policy, like having the option to replace speaking in class with regular written posts give women and non-binary people more space to participate. I have always been more engaged with courses that let me choose how I wanted to display my curiosity and learning,” Rimjhim suggests.

Okay, so what can be done to improve women-in-STEM in the liberal arts and sciences?

Hiring more women faculty members for STEM disciplines is a critical first step, and an open doors policy is not good enough. The rhetoric of not being able to find worthy women applicants creates a vicious chicken-and-egg cycle, and administrators could do well to take a leaf out of hiring practices in the humanities or social science departments. Diversity goals must be set in line with universities’ admission processes for students, and targeted hiring drives are non-negotiable. Where expenses allow for it, departments should consider reaching out to international faculty to meet these goals for diversity, because of its impact on aspiring non-male students.

There is also a need for focussed mentorship programs for women students pursuing sciences, incorporating experience from seniors, alumni, professors, or industry professionals. This network would help fill in as an informal support group, the lack of which hinders the progress of women in STEM fields.

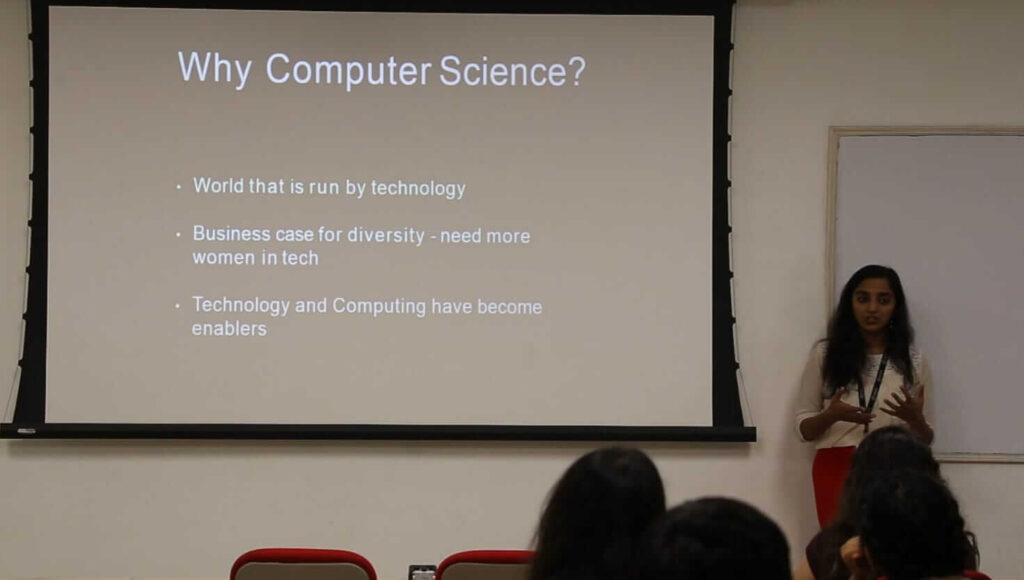

A worthwhile case study in this regard would be the Women in Computing Society (WiCS) at Ashoka University. WiCS is an academic society open to people of all genders and majors who would like to contribute to making a more inclusive STEM environment at the university, especially in computer science.

Through WiCS, Shweta Prasad (Computer Science, ASP ‘22) has had the ability and opportunity to talk to women studying science and create a sense of community and belonging for them. Her mission as a senior member has been to ensure that others in the society are convinced that they belong in science regardless of what their grades or their inner critic say.

“Reiterating time and again that their primary focus should be on their purpose of doing science and on putting in the work consistently makes women more confident. We actively try to distance ourselves from the idea of having the most number of projects or the best grades to be a valid voice in STEM”. Atharvi is also a member of WiCS. She shares how members soon find out that the seniors, who head the society and whom they look up to as mentors and role models, have gone through similar struggles with the disciplines. Atharvi says “Our seniors at WiCS made it a point to repeatedly tell us that Computer Science is hard, that we are not incompetent, and that with effort, things do work out eventually. That helped me become so much more secure of my place in CS”.

Featured image by Nainika Dechamma for The Bastion

*ASP or the Ashoka Scholars Programme is a year-long Postgraduate Diploma in Advanced Studies and Research. Undergraduate (UG) students have the option to pursue the ASP, after their graduation, to pursue research theses or to explore other disciplines further.

Note: The author would like to acknowledge the limitation of this piece. It places focus only on the UG/ DipASR programs of the central case. The arguments may or may not apply to the other cohorts.

Outstanding article on a very pertinent topic, backed by extensive research. Very well written.

Haha…

High Stakes Exams.

Women can’t do that they face anxiety and what not so what should we do lower the stakes make it easier so everyone (shh! Feminist wants only women) could succeed

I mean yeah rather than making our women more confident to take those high stakes we lower the standards and the results are that the whole flock of sheep’s (including female and male) pass out and came for admission.

Dude the high stakes exams are there for a reason to sort out the best of the best who can handle the pressure , the Market that’s ahead of them.

Don’t try to prove your Incapability.

So, try to make our women more confident and not by lowering the standards cuz the world will crumble if idiots (male or female) reach somewhere where they shouldn’t have been.

Like common there are pretty confident out there.

PepsiCo CEO, loreal owner and many more.

If they were the products of lower standards they would not be in that position.

They are there cuz they had the will to take those stakes.

Encourage women with compromising men and without lowering the standards cuz

Let’s hope it’s not that in way of achieving diversification and closing the gap we just have idiots serving and destroying the world market.

Overall the article is fine and I totally agree with some of the points.

Good Go Girl.

Rise up your Confidence and move ahead no one’s gonna stop you

This is an extremely well written piece.