This is the first part of Break the Cycle, a two-part series that explores State priorities in investment in primary and workforce-ready education.

Public education delivery in India has persistently faced a crisis of poor quality, a problem which has now begun to affect the employability of the workforce and India’s global competitive edge. One explanation for the poor state of learning outcomes in India points to the lack of a narrative around the importance of foundational literacy and numeracy (FLN) skills; these are a prerequisite to obtaining strong academic learning outcomes at later stages of education.

While there is plenty of evidence to showcase that superior academic and professional outcomes can be achieved through a strong focus on standardising learning outcomes for primary grade students, the public focus remains on student achievement in the 10th/ 12th board exams. Additionally, there is strong public pressure on polity to ensure access to university education- as this is seen as the primary means to achieve good quality employment. Consequently, from the perspective of resource allocation, higher education is allocated almost double the budget, as compared to the other categories of education..

Even so, the academic learning levels that a student can be expected to attain over time without strong foundational literacy and numeracy skills decrease exponentially over the student’s educational journey. This cannot be disregarded, especially when the Annual Status of Education Report, 2018 found that fifty million children have not attained foundational literacy and numeracy across the country. In fact, the Report states that 73% of third standard students cannot read a second standard textbook, and 81% of second standard students cannot do simple subtraction.

There is clearly an urgent need to strengthen primary education to strengthen overall learning outcomes. This not only requires adequate resource allocation for primary education but also requires changing the public narrative about the benefits of universal attainment of grade-level competency in primary grades.

The question that needs to be answered, therefore, is how to restructure resource allocation within the public education system, in order to achieve superior learning attainment while also serving the immediate requirements of the labour market.

The Resource Dilemma: Can Effective Allocation Improve Primary Education?

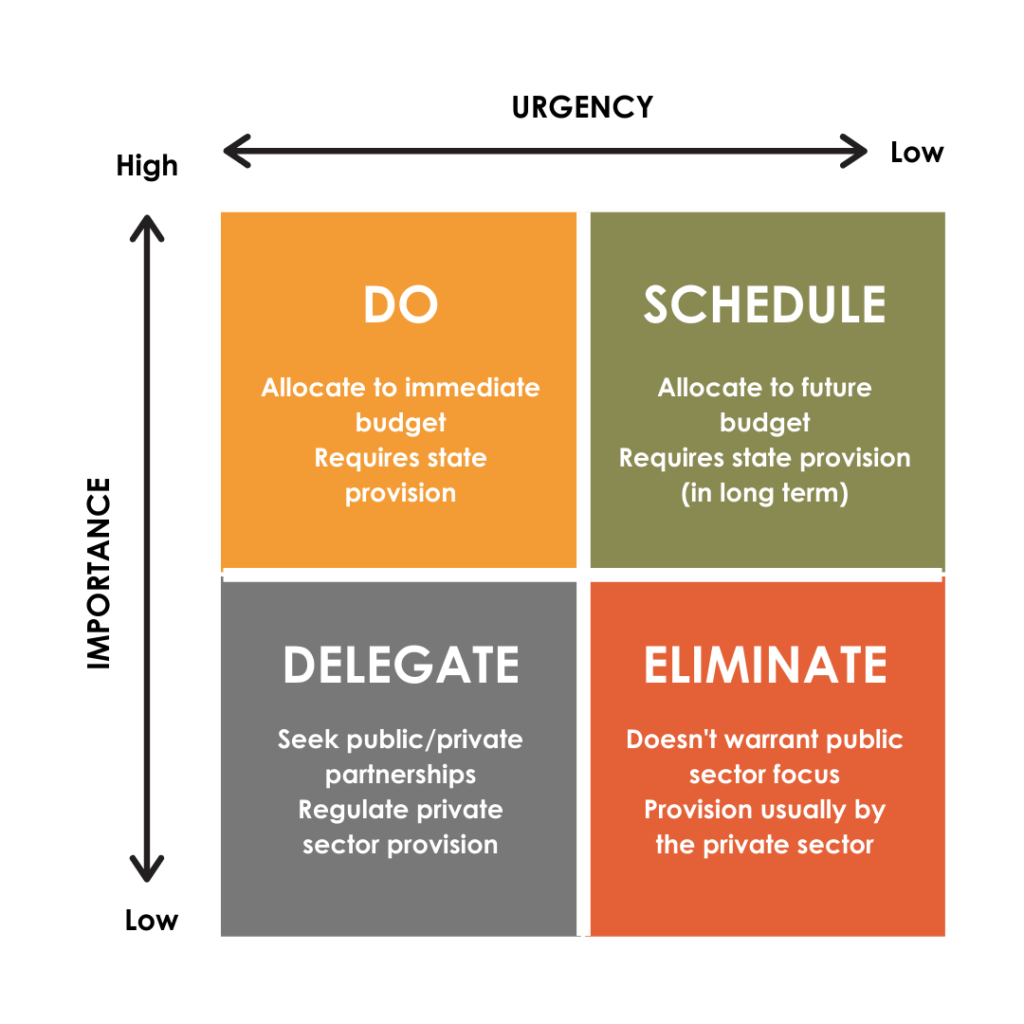

It is a commonly known fact that public sector bureaucrats in developing nations consistently find themselves under pressure to improve public sector performance while containing expenditure. Resources are constrained and there is a significant opportunity cost to every allocation. The Eisenhower Matrix is a simple yet effective tool to aid the thinking process while making policy decisions. It uses a system devised by former American President Dwight D Eisenhower to aid in the process of policy action prioritisation.

The Eisenhower Matrix is a two-by-two grid, divided into quadrants based on the urgency and importance of actions. One must “do” the most important and urgent action immediately, an important but not urgent action can be “scheduled” for later, an urgent but less important action can be “delegated” to someone else, and finally, an unimportant and not urgent action needs to be “eliminated”. Importance in this context refers specifically to the need for public sector oversight and action.

The public education system in India currently has oversight over all the components of the lifetime need for human education. One can assume that the public education system wants to eradicate poverty and enable equitable access to sustainable livelihoods.

Yet, while making such an assumption, one also has to be aware of the fact that life today is sharply different from what it was two decades ago. Technology and lifestyles are progressing at a faster pace than we have encountered before. Accordingly, it is necessary to prepare children who enter the education system today for the world of work that they will encounter by 2040.

The ultimate goal of the public education system should be to ensure that the 12+ years of education that a student obtains can meaningfully support the subsequent 40+ years of their working life. From most students’ perspective, the primary objective of obtaining an education is to be able to access quality livelihood opportunities. Similarly, from an economic perspective, a key purpose of funding the public education system is to be able to service the labour market needs by creating a large pool of skilled labour.

More Resources Can Work Wonders For Primary Education

There is a dissonance between the resource allocation towards primary education and its importance to our students. Poor learning outcomes in primary education lead to a significant dip in the quality of overall learning attainment. A student who has not progressed past the reading level for third grade may graduate until the eighth grade, but with what learning outcomes?

Laxmi Nair, an ex-Teach for India Fellow, commented “Children from low-income backgrounds have far lesser exposure. When I was trying to teach them to read, I realised that their vocabulary was so poor that they were struggling to even express themselves. In my grade four classroom, reading levels varied from students not being able to read at all, to a minority of students being able to read at a third-grade level”.

The Eisenhower Matrix can provide guidance on this urgent and important action—at the end of the day, investing in high-quality accessible primary education can yield strong returns not only for students, but also for employers, and the State. When a child is unable to read or comprehend a third standard text but graduates on to subsequent grades, learning losses compound, such that underachievement in either tenth or twelfth-grade exams is almost a given. Knowledge gaps from primary learning will exacerbate future academic learning losses at an exponential rate. The consequent trend of academic underachievement will compound and the cycle of underachievement will perpetuate itself.

Also Read: Empowering Parents To Demand Better Of Their Child’s Education

However, if a child drops out of formal education after successfully completing the primary grades, they will have picked up the necessary knowledge and skills to a sufficient level where they can choose to continue with any form of further education at a later stage in life. Therefore, high-quality primary education could be key to extracting overall value from the education system.

Despite the importance of high-quality primary education, it can be expensive to obtain, as younger students need higher teacher-to-student ratios and personalised interaction in the classroom. Low-income parents, however, may not be able to afford the opportunity cost of expensive primary education, especially when it cannot be linked to short term economic benefits.

Uniformity in primary education delivery will ensure that all students have access to the same foundational learning. This will also allow the State to deliver primary education, as the resources needed to maintain quality will reduce over time because the subject matter for foundational literacy and numeracy will not change over time. This means that once a solid curriculum is created, it can be deployed without repetitive expenses. Content can be regularly reviewed and updated, which is less resource-consuming, and the saved resources can be re-invested towards alternative problems.

From the perspective of State delivery, the gains to be had from a literate labour force are huge, making the focused delivery of primary education a viable proposition for the State. It helps that State education has the advantage of quality control and uniformity, which can ensure that no child is left behind.

Given the paucity of resources, a focus on primary education might raise the concern that secondary and workforce-ready education would be left with lesser or inadequate resources. This need not be true. Through public-private partnerships, systems for workforce-ready education can be delivered to the masses, with State oversight to ensure equitable access. Such partnerships could free up resources for the governments to focus on primary education while simultaneously ensuring that citizens are equipped with relevant skills to be competitive in the labour market. Public-private partnerships could revolutionise workforce-ready education, if our primary education system receives the resources it is due. More on this to come in Part 2 of Breaking the Cycle, out soon.

Featured image of students sitting with a teacher and engaging in course work. Image credits: Madhi Foundation.