Co-created by Kartik Sundar and Jinson George Chako

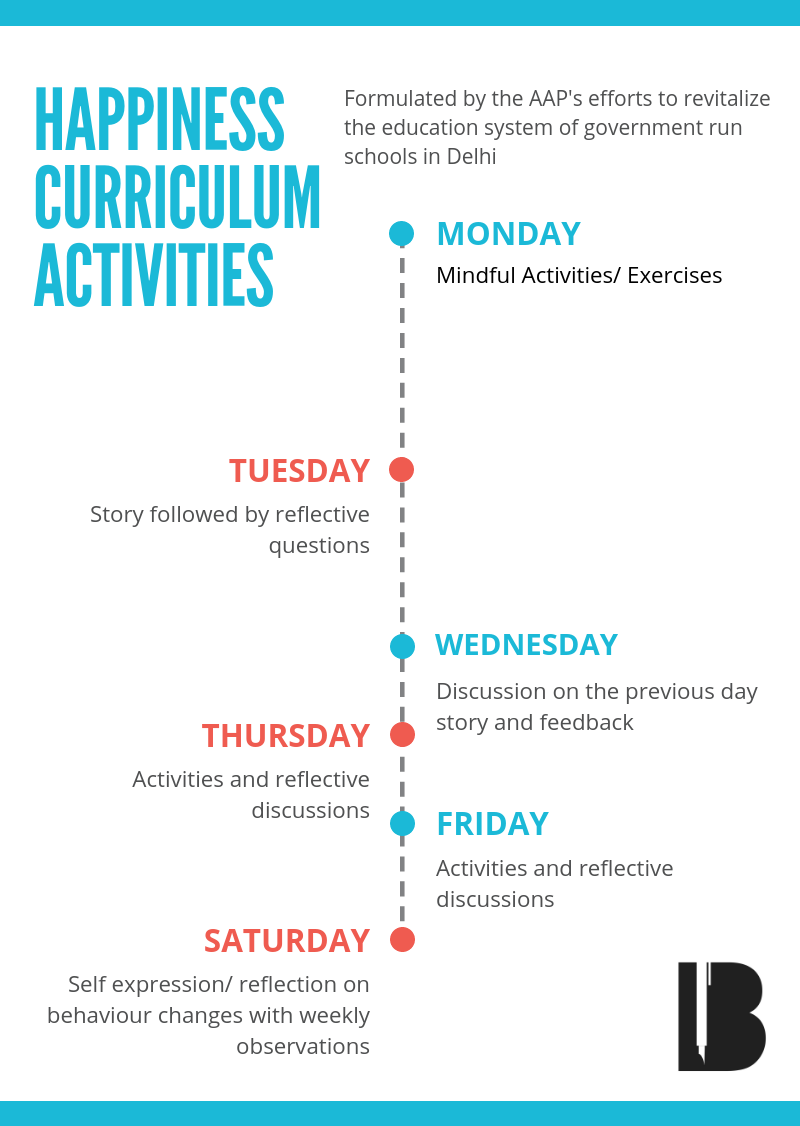

In what seemed like a recognition of the hectic and stressful nature of the Indian education system, the Happiness Curriculum was launched in July of 2018. Inaugurated by the Dalai Lama, the move was part of the Aam Aadmi Party’s reforms for revamping education policies in India’s capital city. For a 45-minute-period in their day, students are encouraged to perform various non-competitive recreational activities such as storytelling, meditating, group discussions and rapport-building games.

The 2019 Amendment to the No Detention Policy has threatened to rear the emotionally-starved nature of our schools. This makes it a good time to ask ourselves if this one period — aimed at inducing a stress-free environment — can really change the mood of classrooms.

The Big Picture

From the earliest stages of education, the onus is on absorbing information as a means to answering examinations. With almost 26% of all students being enrolled in private coaching and some Delhi University cutoffs placed at 99%, the academic pressure affects some students irreversibly. Nearly 20 students committing suicide in Kota (the country’s premier hub for competitive examination coaching) in 2018 alone.

Despite what seems to be a prioritisation for academic excellence and long studying hours, rising dropout rates and high absenteeism in classes has led to a literacy rate that is far from desirable. The all-India dropout average stands at 3.5%; Uttar Pradesh has almost double of that figure, at 6.3%. It does not seem outlandish to attribute part of a poor child’s tendency to forego education because his/her schools and syllabus does not commit itself to make learning an enjoyable and self-reflective process.

How Happy?

The Happiness Curriculum lays a great deal of emphasis on notions of individuality and independence, but it does not change the reality these students are faced with. Ultimately, most undergo the same standardised board examinations and entrance tests. ‘

Happiness’ is often discussed as something that is not fleeting or artificial; its essence lies in the stability and contentment that it can provide. Sure, an hour for themselves would count as a “relief” from classroom rigour, but a thoroughly expansive “Happiness Curriculum” should focus on the long-term mental stability of students.

The overarching cause for the students’ unhappiness and stress remains the incredibly competitive, content heavy, and stressful examination structure that exists at almost all facets of the Indian education system. Due to this problem being very much alive, the happiness curriculum might not warrant the name it proudly heralds.

India’s educational challenges lay in recognising the definitive changes to change public perception, the assessment structure and offer diversification of available higher education. Even if standardised, assessments need to focus on recognising and honing different students’ individuality. Population demographics notwithstanding, Finland boasts a 99% literacy rate, but it has a far less rigorous education system. Schooling only properly begins at the age of seven so that children have more time to enjoy their childhood. After entering the education system, more than any academic discipline, social etiquettes are taught. The student-teacher ratio is kept as low at 1:20, which is an outrageous number for anyone who has attended class at branches of Delhi Public School, for example.

Perhaps more important is that teaching is a profession that is revered in Finland. It is not easy to land a role because it pays well, which goes to show how valued education is as an institution of society. Another pivotal nuance in Finnish education, and one that Indian schools could really benefit from, is the incorporation of vocational studies as an acceptable alternative to formal academic education. With close to half the population opting for vocational studies for honing technical skills, it opens the door for children to dream of specialising in a variety of professions.

The PISA (Program for International Student Assessment) conducts global international surveys that India have been boycotting for close to a decade. However, on the occasion they did take part, they placed 2 spots from the bottom of the list. Although it is an effort in the right direction, the Happiness Curriculum as a standalone will do little to fix the deep-seated dreariness of the Indian education system.

As argued in this article, greater diversification in investments for higher education can create competition for the IITs and IIMs as well as offer different specialisations, through which each student’s individual strengths can be honed. The happiness of our students depends on how we as adults orient ourselves towards the concept of education. Application needs to be emphasized over rote learning and teaching should be a profession that is revered, not derided.

Featured image courtesy Akshaya Patra via Pixabay

[…] You May Also Like: An Optimistic Fix: The Pitfalls of the Happiness Curriculum in Delhi […]

[…] Happiness Curriculum introduced last year also contributed to shifting the focus from a strictly syllabus-based […]