Co-authored by Haya Wakil and Aarathi Ganesan

Most Indian citizens can wax eloquent on India’s’ ancient dynasties and kingdoms, its freedom fighters and perhaps even the modern conflicts which the country struggles with. But many a time, these faces and facts are rooted in India’s mainland states. India’s ‘peripheral’ regions rarely feature in mainstream Indian historical narratives. Constituting what is colloquially grouped as the ‘Northeast’, the states of Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Tripura and Sikkim are victims of this steady isolation.

In the process, the day-to-day triumphs and struggles of their residents have received little public attention across a larger Indian media and citizenry. For example, recent civil disturbances in Shillong which involved a clamp-down on internet services failed to beat #Kairana on prime-time slots of the national media. Otherwise politically active national leaders released no official statements and there was no discussion of the conflict in either house of parliament. Most news received was from a ‘mainland’ perspective which silences voices from the Northeast and furthers relatively uninformed perspectives on the region and its politics.

Encouraging sustained discourse on the Northeast has to be encouraged across the country starting from the ground level. The current isolation of the Northeast and the poor public understanding of it can be largely attributed to an underwhelming academic curriculum; both, school and university textbooks are generally silent on the region and its past. Better representation of the Northeast in historical curricula alongside India’s other local cultures could sharpen its focus in the eyes of students, government and all Indian citizens.

A Borrowed Historiography

Since Independence, the Indian education system has secluded the histories of more than 45 million Northeastern citizens (who currently account for nearly 4% of India’s population). To a layperson, the Northeast is nothing more than a handful of stereotypes of being home to insurgents, terror attacks, and AFSPA violations. Beyond these tropes lies a rich historical record displaying the cultural and political prowess of the Northeast which is overshadowed by the legacies of the Mughals and Mauryas in history textbooks. Continued exclusion points to selective readings of an ‘Indian’ past, one that is largely rooted in colonial administrative strategies.

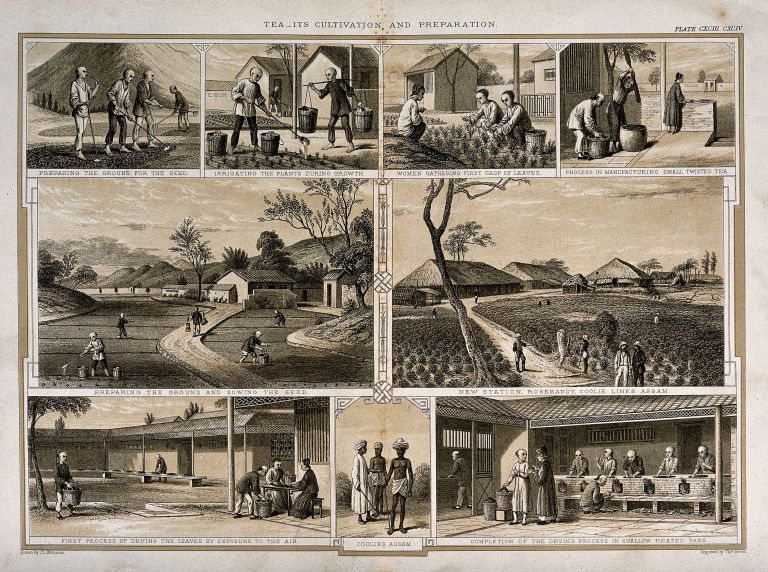

In an email exchange with The Bastion, Dr Sukanya Sharma, Professor of Archaeology and Cultural Studies at IIT Guwahati, points out that the British Raj had clear intentions to isolate the Northeast for its own gains. Doing so secured the supply of tea, oil and timber while simultaneously creating a strategic buffer between French Southeast Asia and British-controlled Northeast India.

According to Dr Sharma, “to isolate Northeast India, major verifiable historical sources were disturbed. In fact, a whole new government department [Department of Historical and Antiquarian Studies] was created to write a history of Northeast India highlighting Southeast Asian linkages. The hill communities were clubbed as ‘uncivilised, savage’ by using powerful mediums like ethnographic accounts (J P Mills, Verrier Elwin, Haimendorf etc.), and described as so primitive that they had no history.”

This is far from the truth; verifiable historical evidence and artefacts available spanning from coins of the 7th century AD to temple ruins which still exist in Assam, as refutations to such political historiography.

Unfortunately (as is the case with much of India’s history), colonial accounts of its past persisted post Independence. Dr Sharma notes the appointment of Verrier Elwin, a colonial missionary-cum-ethnographer, as the “Anthropological Adviser to the Government, of present-day Arunachal Pradesh”. Also serving as a governmental advisor on tribal affairs, Elwin’s own colonial biases and influence “made authentic records/sources inaccessible to the larger academic circles of the country. [Post Independence] Historians had less interest as Northeast India was best described as a ‘living anthropological museum’.” With “verifiable sources [of a Northeastern past] eluding mainstream history writers,” the region’s exclusion across syllabi appears somewhat less surprising.

Yet, this historical amnesia extends well into the better-recorded modern era as well. The Northeast states have played indelible roles in India’s freedom struggle, since as far back as the 19th century. The Battle of Imphal-Kohima during World War II greatly influenced the Indian freedom movement and galvanized mass public demonstrations, eventually inspiring the revolt of the Royal Indian Navy in 1946. Although voted as the ‘greatest British battle’ by the National Army Museum in London, Imphal-Kohima remains largely forgotten in India alongside scores of other movements and martyrs of Northeastern origin.

Multilateral Repercussions

A selective reading of the past has widespread repercussions on current national ideals of diversity and development. Shikha Dwivedi, a student of History at Delhi University points out that “while this [Unity in Diversity] has definitely been able to create the idea of a nation, it has simultaneously led to identity crises amongst the alienated communities. [Their] dissatisfaction with the present state of affairs is evident from the secessionist movements that are continuously threatening the ‘unity’ of India”.

Such cultural alienation is aplenty in a news media environment that possesses the potential to improve the visibility of the Northeast and its cultures. This lack of representation in the media and our textbooks cascades onto bureaucratic understandings of the different socio-economic and political circumstances which affect Northeastern states, which hinders policy formulation and implementation. Often, the laws so introduced act as an imposition to its people and sanctioned schemes suffer from poor implementation.

The lack of infrastructure, development and opportunities for the youth have resulted in a brain-drain from the Northeastern states into metropolitan cities. Apart from landing up in a new environment with stiff competition for education and jobs, citizens’ lack of awareness about the Northeast which stems from its historical exclusion often results in prejudiced and derogatory interactions.

The Reform Has Already Begun

In recent times, governments and educational authorities have become increasingly cognizant of redesigning educational curricula to account for the Northeast’s past and future. In 2012, Manipur Women Gun Survivors Network and Northeast India Women Initiative for Peace began a movement demanding the inclusion of the region’s history in mainstream textbooks.

The following year, a seminar was held in New Delhi which demanded the inclusion of its history in India’s educational curricula. The event concluded with the establishment of the ‘Northeast India Resource Group’ which consisted of historians, educationists, and scholars. ICHR, NCERT, and CBSE pledged full support towards the initiative.

In 2017, these efforts came to fruition: the NCERT commissioned a supplementary reader titled North East India: People, History and Culture with the objective of inculcating interest amongst children. Although a step in the right direction, it remains unclear as to why the region’s history failed to make it to general history textbooks in the first place. The Centre’s commitment to such initiatives remains somewhat dubious.

Quite literally introducing such regions as being ‘separate’ from a larger Indian history only furthers innate biases amongst young learners and the general public. As Dr Sharma iterates, “one needs to teach it as nothing special, but as a very normal/natural part of pan-Indian historical development. The whole idea that Northeast India is different from rest of India is wrong and should never be the ‘starting line’ for deliberations on Northeast Indian history.”

Being a major stakeholder in the Centre’s ‘Act East Policy’ could aid the Northeast’s assimilation process. India is keen to consolidate its position as a major South-East Asian ally, and the Northeast is the key that connects this region to the Indian mainland. Consequently, the Cabinet has passed many schemes to promote industrial development and improve connectivity in the region — to the tune of 45,000 crore rupees. Such attempts at capacity building could help transform the Northeast into an economic hub and boost its image and presence in mainlanders’ eyes.

Turning the Page

While official histories in India are typically malleable and controversial, at least they keep alive the debates and legacies surrounding different cultures and communities. The comprehensive neglect of the Northeast’s history for over 70 years (despite disputed claims over the territory) is an anomaly in this regard. It has silenced an entire region, leaving behind fractured social relations and impressions across past and future generations.

If the nation is to show for its steadfast claims of integrating its ‘peripheral’ territories, honest efforts must be directed towards including the region, its peoples, cultures and histories into its structural fabric. India’s educational curriculum is a vital place to start off at.

[…] find that the state system itself, however unintentionally, perpetuates this treatment. Take our school textbooks for example; when learning about the history of India, there is barely any, if at all, mention of […]