This article is the final instalment of our three-part series on how exclusionary colonial conservation plays out in Uttarakhand’s Rajaji Tiger Reserve. Click here to read part one on how this model impacts the wildlife the Park seeks to protect. Click here to read part two on how this model impacts the rights of the Van Gujjars living here.

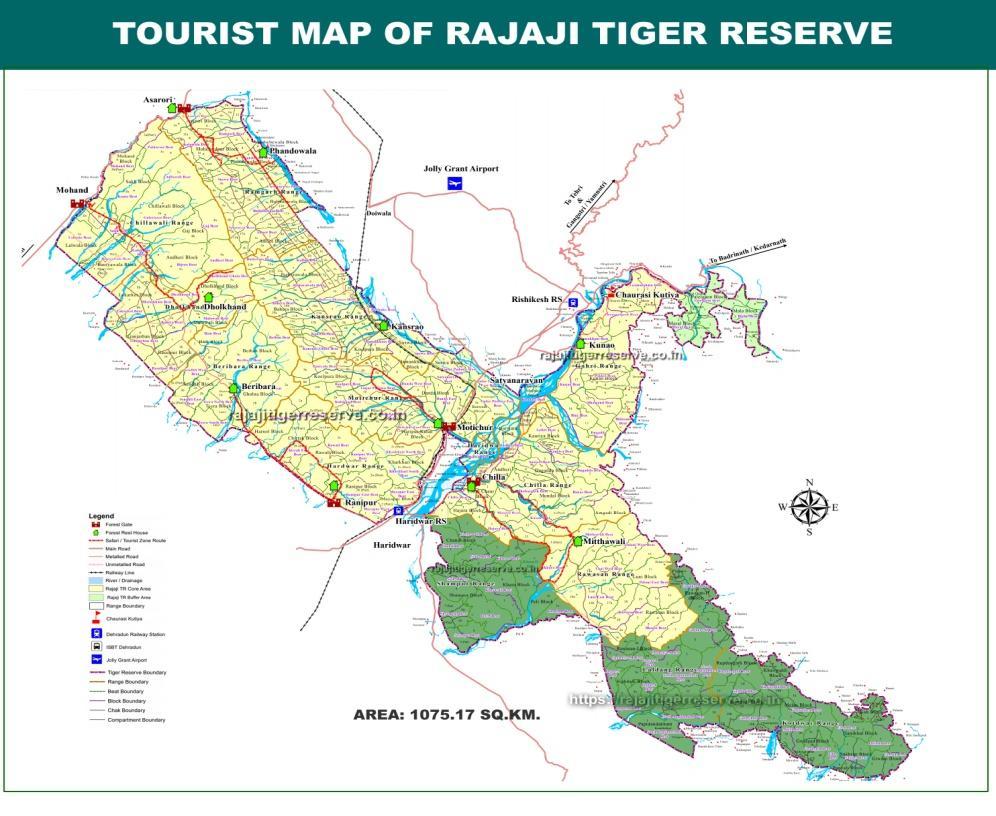

On 15 April, 2015, the Central government awarded Rajaji National Park the status of a Tiger Reserve—making it the 48th Tiger Reserve in the country and the second of its kind in Uttarakhand. The declaration of an area as a National Park or Tiger Reserve is representative of the State’s outlook on conservation in India, which follows a stringent centralised protected area governance structure.

But, as parts one and two of this three-part series on Rajaji National Park reveal, the State’s conservation practices are born out of convenience rather than concern for ecology.

Part one explored how over the years, consistent developmental interventions have fragmented Uttarakhand’s mountain and forest ecosystems to the detriment of both indigenous species residing in RNP and wildlife conservation. Shedding light on the blatant denial of statutory clearances for development projects, power conflicts within State apparatus, and the Uttarakhand government’s evident apathy for wildlife, the instalment pushes us to reinvestigate the role of the State as a ‘guardian of conservation’. Part two explored how the cost of such State-led conservation is borne by Van Gujjars, a Muslim nomadic pastoral community living and moving with their herds of gojri (buffaloes) in RNP’s areas for decades. Since the establishment of RNP, Van Gujjars have been subjugated to forceful uprootment, false charges, evictions, persistent harassment, and violence, all legitimised by the State in the name of conservation.

This is all happening despite the existence of progressive legislations in India. The Forest Rights Act, 2006 (FRA) recognizes the historical rights of forest-dependent and pastoral communities. Along with the Wildlife Protection Act (WLPA Act) and the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) guidelines, these powerful legal instruments provide legal rights and rules for the coexistence of wildlife and forest-dependent communities within protected areas like this one.

Yet, as this series shows, these laws remain unimplemented and not complied with by the State, which maintains an apathetic attitude towards the recognition of the forest rights of Van Gujjars. Far from practising a conservation of coexistence that centres forest-dependent communities, the State continues to exclude Van Gujjars from forest lands and pastures. As a result, Van Gujjars are awarded the labels of outsiders, encroachers, and threats to wildlife by the Uttarakhand government, bureaucracy, and even the judiciary.

This study reveals how the State’s understanding of conservation remains deeply buried in colonialism, casteism, and centralised governance—all of which are inherently exclusive in their perspective and practice. It is these exclusionary, rigid, Protected Area governance models that have historically failed to understand the Van Gujjars and their pastoralism.

In the final instalment of this series, we explore how the State’s exclusionary conservation models at Rajaji National Park play out. With deep-seated biases and prejudices governing institutes of power and knowledge, the forest rights of Van Gujjars and their critical role in conserving Himalayan ecology remains cornered.

State Perceptions of Moving Lives

“Our seasonal movement evolved alongside the concern of conserving forests,” explains Meer Hamza, President of the Van Gujjar Tribal Yuva Sangathan and from one of the few Van Gujjar families living in Rajaji National Park. “We move to give time to the forest and pastures to replenish. We Van Gujjars moved freely in rotation [with the seasons], and with flexibility across vast stretches of the Shivaliks.”

Being a mountain pastoral community, the Van Gujjars evolved interdependently with the surroundings and the seasonal variability in climatic conditions. Their lives are intertwined with an ecological rhythm here and are adapted to changes in seasons, ecological zones, altitudes, and mountain environments. They are one of the very few pastoral communities that still travel with their entire families in tow. In this way, Van Gujjar nomadism is an exercise in survival and climate resilience.

The Van Gujjars also hold a historically critical role in the region’s economy as providers of milk and dairy products. The community is essentially dependent upon its herds of buffaloes for sustenance, which is why they rely on the availability of and access to nutritious grasslands and pastures. Such transhumant grazing practices produce enriched manure that benefits both the settled agriculturalists and the forest ecosystem.

The Van Gujjars traditionally lived in houses called deras made out of sticks, dried leaves, thatched grass, mud, and other locally sourced materials provided by the forest. They also hold a deep knowledge of the indigenous flora, fauna, medicinal herbs, and forest products that they carry with them.

In short, the Van Gujjar way of living embodies in them gratitude to, responsibility for, and accountability to the local ecology.

Yet, accusations of overgrazing and environmental degradation by the community, are rooted in how both the colonial State and postcolonial democratic India—in their imaginations of landscapes shaped by physical boundaries, fences, and surveillance—have gazed at pastoralists as misfits. As Bhattacharya elaborates [1], the State thus labels the Van Gujjars as ‘old’, wild, and uncultured as compared to peasants and settled agriculturalists who are seen as settled, cultured, and ordered.

State policies there onwards have tried to control the pastoralists by settling them into a fixed portion of land, and shifting their communal management of forest resources to individualised understandings of access, grazing, settlement, permits, and property. In the pursuit of the fortress conservation model and making wildlife areas inviolate, or free of humans, the Van Gujjars across Uttarakhand continue to be labelled as encroachers. This results in their evictions and evident exclusion from accessing and managing forests.

As Dr. Nitin D Roy and scholars from ATREE elaborate, such a conservation model is rooted in the belief that “forests are pools of Capital: tourism, timber; it fails to see forests as living spaces of coexistence of species, including humans.”

For example, in 1996, the Van Gujjars of RNP, with support from a local NGO called Rural Litigation and Entitlement Kendra (RLEK), proposed a Community Forest Management Plan for Protected Areas to forest and RNP authorities. The plan proposed the active participation of Van Gujjars in the management and conservation of forests, by linking the survival and sustainability of forests with the sustainable lives of the Van Gujjars. The plan was ignored as it was too progressive for the time and the existing provisions of WLPA did not permit human activity in protected areas. So, the Forest Department continued practising its colonial conservation models and community forest management remained a dream in RNP.

The Van Gujjars saw new light with the enactment of the Forest Rights Act, 2006, a piece of legislation that recognized the historical rights of forest-dependent and pastoral communities. Yet, after more than 15 years of the enactment of the FRA, the forest rights of Van Gujjars and their critical role in conserving the environment continues to be denied any voice in the management of forest and conservation discussions.

The Destructive Faces of ‘Conservation’

The amendments to the Wildlife Protection Act of 2006 focused on the coexistence of communities and tigers in Tiger Reserves. The FRA too emphasises on the critical role of communities in conservation, providing legal rights for the same. Given these progressive legal instruments, it is tragic that the State still continues to practise colonial, top-down, centralised, and exclusionary conservation governance in Rajaji Tiger Reserve.

The spread of COVID-19 and the state-imposed lockdown measures that followed in March of 2020 marked a traumatic turn for the Van Gujjars living here.

The community was at the receiving end of violent discrimination in the light of growing (and partially) State-led religious polarisation post the Tablighi Jamaat controversy. From May of 2020 onwards, markets surrounding RNP refused to buy milk from Van Gujjars. When people did not refuse, they negotiated the purchase at cheaper rates.

Adding to these livelihood insecurities, the Van Gujjars faced further roadblocks with the Forest Department and Park authorities blocking their migration citing the potential risk of COVID-19 transmission from the Van Gujjars to the animals.

Then, on June 16 and 17 of 2020, forest officials along with police personnel arrived at the dera of Mustafa Chopra’s family without any show-cause notice and started destroying the deras, and harassing and assaulting women. The police later took some of the Van Gujjars into custody on false and frivolous cases. They also reportedly inflicted brutal assaults on women, especially on Noorjahan Chopra’s daughter.

Importantly, these deras are located at the Asharodi forest in the Ramgarh range of Rajaji National Park, about 500 metres from the Dehradun-Delhi highway—a major infrastructure project passing through the state. The summer of 2021 was no different.

In May, the Deputy Director of Uttarakhand’s Govind Pashu National Park prohibited 150 Van Gujjar families from entering their summer bugyals (or alpine pastures) located inside the park’s core and buffer zones—these summer homesteads are located at a higher altitude, and provide grass and some respite for the community and its cattle during the hotter months. The bureaucratic apathy—legitimised in the name of protecting animals in RNP—resulted in the death of 500 buffaloes, all of whom had been subjected to unbearable heat at lower altitudes. Later they were allowed entry when the Uttarakhand High Court slammed the authorities for making the community live in “conditions worse than animal existence”.

These stories of bureaucratic discrimination towards Van Gujjars feed into a larger irony of the State’s conservation perspectives, which are inherently exclusive: they also fail in securing and preserving the ecosystems at RNP in the short and long run.

“The Forest Department just wants to cultivate teak plantations in the RNP. But, plantations are lethal to the forest,” remarks Rajneesh, a member of the All India Union of Forest Working People (AIUFWP). “Teak and pine plantations have not only wiped out grass cover but also upscaled the forest fires here. There is [also] large-scale felling of trees for roads and other big [development] projects but nobody checks [how this will impact the conservation of the area].” The State’s push for monoculture teak and pine plantations continues in spite of their detrimental impacts on local ecology. Here too, the knowledge, experience, and relationships of locals and forest-dependent communities with the forests are discarded, with officials reducing them to daily wage labourers under plantation schemes with no expertise.

Part one of this series further describes how development projects in RNP have bypassed legal environmental clearances, often to the detriment of the tiger and elephant populations it seeks to protect. Recent actions by the Uttarakhand government strengthen this pattern of exclusionary conservation.

In November of 2020, during the 16th meeting of the State Wildlife Board headed by former Uttarakhand Chief Minister Trivendra Singh Rawat, the committee decided to de-notify the Shivalik Elephant Reserve to allow for the expansion of the Jolly Grant Airport [2]. In the same meeting, proposals of Laldhang-Chillarkhal road projects that affect wildlife in RNP were resubmitted to the National Board for Wildlife (NBWL) with limited protections for wildlife.

Legally, the state government has no power to de-notify a protected area. In its response to the move, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MOEFCC) clearly emphasised that the reserve area holds “High Conservation Value” and any diversion will result in “fragmentation of the riverside forests which is situated between the existing runway and the river.” The expansion of the airport in the reserve area will also result in the cutting of more than 10,000 trees.

A PIL on increasing elephant deaths raised this case in the Uttarakhand High Court—the Court later ordered an interim stay on the project on January 8, 2021. Yet the state government, bypassing the WLPA of 1972, the Forest Conservation Act of 1980, and court orders, de-notified the reserve on the same day. The Uttarakhand Forest Department, in September of 2021 also announced that it received a sum of ₹39 crore under CAMPA from the MoEFCC for the man-wildlife conflict mitigation project. The money is to be majorly used for building barriers—in the form of elephant-proof trenches and a 280-kilometre long fencing—to prevent wildlife from entering residential spaces.

In Whose Name is the State Practising Conservation?

In June of 2021, Uttarakhand’s Forest and Environment Minister Harak Singh Rawat announced that the Rajaji and Corbett Tiger Reserves would now be open round the year for tourists. They otherwise remained closed from 30 June to 15 November. Further reports indicate that in a letter dated 3 September, the Chief Wildlife Warden of Uttarakhand requested the director of Rajaji Tiger Reserve to open the areas between Satyanarayan to Kansro, a critical tiger habitat in Rajaji Tiger Reserve, to tourists for the whole year.

These four months are the prime mating seasons for wildlife, especially elephants. Taking this into account, the guidelines issued by the NTCA in 2016 ban the movement of tourists during monsoon, to maintain a favourable and peaceful environment for wild animals. The National Wildlife Action Plan of 2017 also clearly elaborates that in case of a conflict between tourism and conservation in the wildlife areas, conservation prevails.

In this light, opening the reserve for the State’s own profit shows a flagrant indifference towards wildlife. Such ‘conservation’ approaches are all the more alarming as already more than 170 elephants have died in Uttarakhand over the past five years, at the rate of two dozen deaths per year. On 10 February, 2018, the National Green Tribunal even directed the MOEFCC and NBWL to take cognisance of the deaths of wild animals due to the highway. An attached report from the Wildlife Institute of India highlighted how 222 wild animals of various taxa were killed in 2016-17 due to the buzzing traffic within the 30-kilometre patch of the National Highway 74 passing through the Haridwar forest division. The tigers, as described in part one of this series, continue to face issues of skewed population distribution as a result of ‘road development’ in the Park.

It is no wonder that in a letter dated to 6 October of 2021, the NTCA, acting upon legal notice from the Supreme Court, asked the Chief WildLife Warden to cease all kinds of tourist activities in RNP’s core and critical habitat zones with immediate effect. As reported in a letter dated 8 October from D.K. Singh, Director of RTR, “tourism activities in Chila [sic] range, Rawasan unit and Motichoor range have been suspended with immediate effect.” But, in light of the issues the Park is facing, such actions only scratch the surface.

आज शिवपुरी रेंज निवासरत गुज्जर परिवारों को पिछले कुछ दिन वन क्षेत्र से बेदखल करने के दिये गये वन विभाग के नोटिस का प्रतिउत्तर तत्समय दे दिया गया था आज राज्य व कैन्द्र सरकार के सम्बन्धित अधिकारियों माननीय मंत्रीयो आयोगों को पत्रचार किया गया pic.twitter.com/nVruaaVNNE

— Van Gujjar Tribal Yuva Sanghatan (@VanYuva) April 19, 2021

The story of Rajaji Tiger Reserve is one of unimplemented laws, the denial of rights, coercion, brutal displacement, and human rights violations. This is a case of multiple levels of exclusion, where the State and Forest Department have conveniently maintained their hot seats of power and oppression.

Here in the name of inviolateness Van Gujjars are excluded, and in the name of development, conservation is excluded. In this story, Van Gujjars are not citizens enough and buffaloes are not animals enough, and tigers are exclusively discussed in the context of safaris and sightseeing. Our forests are exclusively reserved to the wills and ways of various government departments.

In Rajaji Tiger Reserve, where the government abides by conservation of its own convenience, both the Van Gujjars and wildlife remain deprived of their free movement, surviving on the remnants of freedom thrown to them by the state.

The Reserve also embodies in it the global story of exclusionary conservation politics and centralised conservation practices—their unwillingness to decentralise and share power has perpetuated violence on local and indigenous communities. This is a framework that epistemically fails to understand the coexistence of species. A report by Rights and Resources estimates that “up to 136 million people have been displaced in the name of formally protecting half of the Earth’s currently protected area (8.5 million km2).”

For any change to happen, the Uttarakhand government must take cognizance of the Forest Rights Act and recognize the role and rights of the Van Gujjar community in conserving mountain and forest ecosystems. In the implementation of the FRA, the Uttarakhand Forest Department maintains a strong position of power, which needs to be accounted for as it has adversely affected the claims process. The Ministry of Tribal Affairs must also take responsibility for its roles and responsibilities and act in all its power.

Unless there is a paradigm shift from this colonial developmental conservation towards a collaborative, collective, community-led, and anti-caste approach, both wildlife and communities will remain endangered inside protected areas. But, this shift must refrain from romanticising the traditional community practices which, in the context of the Indian State, implies a caste and gender-based hierarchical access to ecology.

The other traditional forest dwellers in FRA must not remain othered and invisible. The Van Gujjars need to be the authors of conservation not the victims of it; they need to be recognized as epistemic sources of knowledge.

This article is based on a detailed case study compiled by the author for the Centre for Financial Accountability. The author pays gratitude and credits to Mr. Meer Hamza, President of the Van Gujjar Tribal Yuva Sangathan, a youth activist, and a resident of Rajaji National Park. The author thanks Meer for sharing their knowledge, perspectives, and critiques, and for being a great storyteller.

Featured image: Rajaji National Park, Uttarakhand; courtesy of Raj Dhiman on Unsplash.

[1] Bhattacharya, N. (1995). “Pastoralists in a colonial world”, in David Arnold and Ramchandra Guha (eds.) Nature, culture and imperialism, essays on the environmental history of South Asia. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

[2] Importantly, the reserve is located to the south of the airport. Expansion towards the north is not possible as this is where the settlements of displaced Tehri families lie. These are another group of Pahari people—or mountain dwellers—historically marginalised by the developmental state.

[…] reality, a community-versus-environment framing of forest conservation continues to operate in India. Following Hardin’s metaphor, State […]

[…] Also Read: A Conservation of Convenience: The Politics of Exclusionary Conservation Models in Rajaji National P… […]

[…] read part one on how this model impacts the wildlife the Park seeks to protect. Click here to read part three on the larger underpinnings of such conservation […]