This article is the second instalment of our three-part series on how exclusionary colonial conservation plays out in Uttarakhand’s Rajaji Tiger Reserve. Click here to read part one on how this model impacts the wildlife the Park seeks to protect. Click here to read part three on the larger underpinnings of such conservation models.

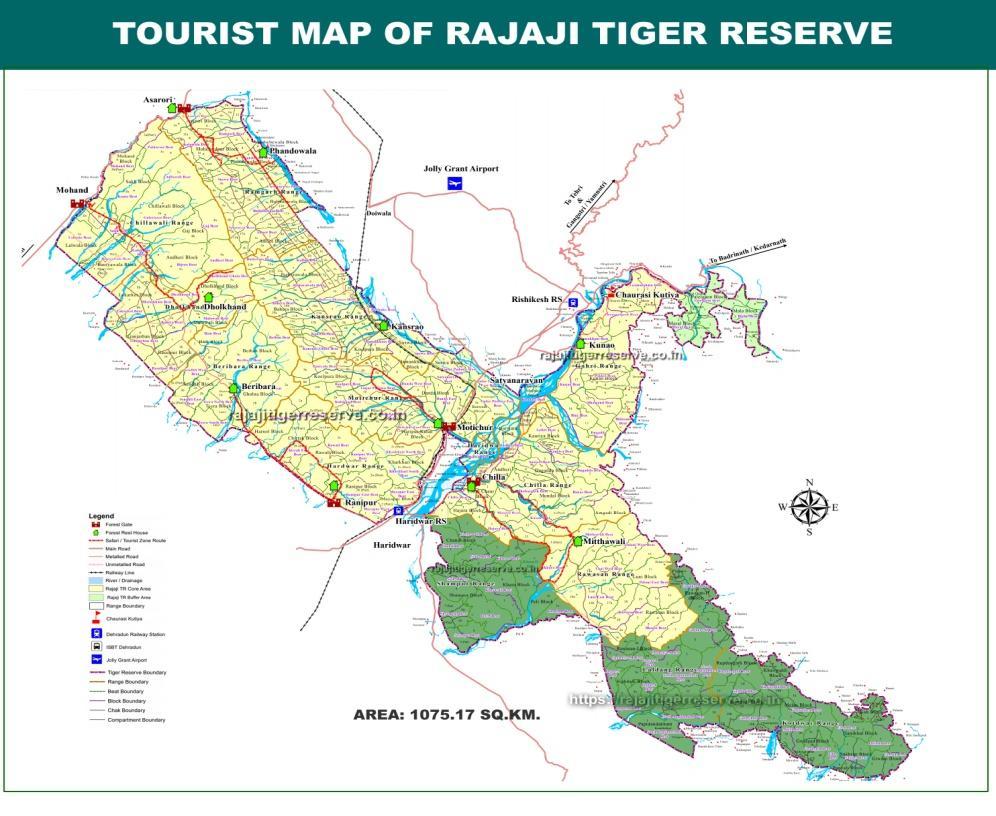

On 15 April of 2015, the Central government awarded Rajaji National Park (RNP) the status of a Tiger Reserve—making it the 48th Tiger Reserve in the country and the second of its kind in Uttarakhand. Yet, as part one of this series has noted, consistent developmental interventions in this Park hinder the conservation and protection of the hundreds of indigenous species living here. The Van Gujjars, a Muslim pastoral community living in this area for decades, and critical to conserving local ecology also find themselves at the receiving end of the State’s ‘conservation efforts’ in RNP.

The lives of the Van Gujjars are intrinsically woven with the forests and surrounding lands. They live with the herds of milk buffaloes they rear in the Western and Central Himalayas. Practitioners of transhumant pastoralism, their livelihood depends majorly on the production, exchange and sale of milk and milk products.

With the beginning of summer, the community along with their herds migrate to the bugyals—or grasslands—located in the upper Himalayas for grazing. At the end of the monsoon, they return to their hut settlements—or deras—at the foothills of the Shivalik range. The community shares a sustainable, sacred, flexible, and symbiotic relationship with forests and wildlife. Along with the Van Gujjars, the landscape here is shared by four Taungya villages and other Pahari communities also dependent upon forests [1].

The Forest Rights Act, 2006 (FRA), recognizes the rights and role of forest-dependent and pastoral communities in forest conservation, providing them with legal provisions and rights over forests. Along with the Wildlife Protection Act (WLPL Act) and the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) guidelines, the FRA is also decisive in defining the critical role of communities in conservation. It lays down rules for the coexistence of communities and wildlife and the residence of forest-dwelling communities within protected areas like this one.

The FRA—through Section 2(a)—recognizes the rights of pastoral communities such as the Van Gujjars over customary common forest land within the traditional or customary boundaries of a village. For pastoralists, this includes prescribing the seasonal use of landscapes like reserve forests, un-demarcated forests, unclassified forests, deemed forests, protected forests, sanctuaries, and national parks.

Yet, in practising exclusionary conservation models at RNP, State apparatuses continue to act in violation of both forest rights and environmental laws, to the detriment of the Van Gujjars. Amidst Uttarakhand’s lack of political will in recognizing the Van Gujjar’s FRA claims, the community faces regular and violent harassment and evictions from the Park, on the largely unproven basis that its members are ‘degrading’ its environment here.

This is despite the fact that the FRA provides security against evictions, clearly stating that no person should be evicted from their forest land until their forest rights have been settled. When it comes to wildlife conservation, the FRA also specifies that local communities should be relocated from critical wildlife habitats only if the state government has exhausted the coexistence of wildlife and community as an option, and if the activities of forest rights holders will cause irreversible damage to wildlife species and their habitats.

These conditions are hardly satisfied in the case of Rajaji National Park’s Van Gujjars. In part two of this series on what conservation looks like at Rajaji National Park, we explore the consequences of exclusionary colonial conservation on the pastoral communities living inside protected areas.

A History of Losing Homes for ‘Conservation’

Due to the community’s pastoral and nomadic lifestyle, the Forest Department (FD) initially lacked accurate data on the number of Van Gujjar families residing within RNP. This lack of data means that there should be little scope to judge the size of the community and thus the scale at which they are supposedly degrading the environment in RNP. Yet, since 1983, when this stretch of Uttarakhand was notified as a National Park, there have been multiple instances of the State-led targeting of the Van Gujjars as encroachers, poachers, and bulwarks to wildlife conservation. This has resulted in the massive eviction of Van Gujjars from their homelands.

In a Down To Earth report from 1992, Shamser Ali Bhadana, a Van Gujjar youth then working on a population and livestock census, was quoted as saying “as many as 3,000 [Van] Gujjar families have lived in the RNP park area for more than 50 years. Another 4,000 families live outside the park. About 170,000 [sic] non-Gujjar families who stay in the 216 villages in the Ghaad region outside the RNP have customary rights to the forest.” Members of the community told this author that the Department identified 881 new Van Gujjar families in its second survey in 1998—due to the community’s migratory nature, these families were not included in the 1983 survey.

In 2016, Neena Aggarwal, Director of RNP, commented on the disparities of the official figures: “it is so difficult to arrive at a certain figure and thereby a solution in terms of [Van] Gujjar counting since every time the census is done, some more names of the community people come up.” As per the reported count, in the 1998 census, the number of Van Gujjar families was 1,395, and by the 2009 census, the total was 1,510.

Yet, despite the lack of consistent data, the years following these reports saw the Van Gujjars both facing and resisting the Forest Department’s efforts at forceful evictions. These evictions did not follow any due process and no prior notice was offered to the community. Reports suggest they routinely include human rights violations, damaged belongings, and psychological harassment and manipulation by State authorities, on the basis that the Van Gujjars were justified by labelling these communities as encroachers on protected areas. In the meanwhile, the Department maintained stringent restrictions when it came to accessing the forest, while many Van Gujjars were charged with false timber cases.

By 1998, out of the 260 listed families in Chillawali range, 209 families were moved to Gaindikhata village. Post the 1998 survey, the Department began the relocation and resettlement of 1,393 families to the Gandighetta and Pathri ranges, promising them an acre of land and a house.

The Reality of ‘Relocation’ and the Perils of Staying Behind

For many families, the rehabilitation process was never completed, it was mere relocation—a devastating turn of events for them. “Many families moved under coercion because they were told there’s no alternative. Most of them found themselves in shanty shacks located at the periphery of the Rajaji National Park, on the banks of the Ganges, awaiting the ‘Promised Land’ pattas [documents],” recalls Tarun Joshi, convenor of the Van Panchayat Sangharsh Morcha, an Uttarakhand-based organisation working with forest-dwelling communities for the recognition of their forest rights and Van Panchayat governance.

आज वन गुज्जर ट्राईबल युवा संगठन द्वारा लालढांग रेंज उत्तराखंड के वन गुज्जर समुदाय की ग्राम वनाधिकार समिति का गठन किया गया pic.twitter.com/OZzdOgxrGd

— Van Gujjar Tribal Yuva Sanghatan (@VanYuva) April 1, 2021

Such accounts prompted the remaining families to resist the State’s forceful evictions. Some families came back too. Yet, with departmental harassment and evictions intensifying with time, the Van Gujjars—under the banner of the Ban Gujjar Kalyan Samiti—approached the Uttarakhand High Court in 2005. The community also joined the national movement against forceful evictions of forest-dwelling communities and the National Campaign for Forest Rights—which ultimately resulted in the enactment of the Forest Rights Act in 2006. With the passing of the FRA, the Uttarakhand High Court continuously ordered the then director of RNP to acknowledge the community’s rights under the law.

In 2008, in spite of all the legislative progress against forceful evictions, the same Court served the director of RNP with a contempt notice for violating previous orders by forcefully evicting and resettling the Van Gujjars outside the park. By October of the same year, the Van Gujjar Communities protested en masse against the Park authorities for forceful evictions and demanded recognition of their forest rights. Subsequently, the Court also directed the Uttarakhand government to form a committee to ensure that within two months both the forest rights of Van Gujjars are settled under the FRA and that the process for filing claims be monitored. These judgments brought temporary cheer and hope for the community, yet down the line, the future of forest rights remained unchanged.

In 2009, the Department completed its third survey of the Park and recorded a total of 1,610 Van Gujjar families. Over the years, most of the families have either been manipulated into relocating or forcefully uprooted.

Those who have protested and are left behind continue to be routinely harassed. On 28 June 2011, the Uttar Pradesh Police detained Noor Jamal, a Van Gujjar, from the Park at Biharigarh Police Station. Noor Jamal was a member of BGKS. The police acted on false charges filed by the Forest Department and Noor Jamal was released only after strong mass protests from the Van Gujjars.

On 26 November, 2013, then Uttarakhand Chief Minister Vijay Bhaguna approved the proposal to rehabilitate 228 Van Gujjar families living in Chillawali Range of RNP. They were to be relocated to Shahmansoor Reserve Forest in the Haridwar forest division.

Currently, only 129 families reside within the park; 120 live in the Gauri Range and the remaining 9 in Ramgarh Range. The FRA seems to have been able to do little to secure their rights to their homes, a malaise that affects the rest of the forest-dwelling communities here too.

Uttarakhand: A Case of State Apathy Towards Recognising Forest Rights

In Uttarakhand, where 71% of the geographical area is recorded as forest land and a majority of the population is forest-dependent, the implementation of the Forest Rights Act has been laggard. According to the Ministry of Tribal Affairs (MOTA)—the nodal agency responsible for implementing the FRA—out of the total of 6,665 forest rights claims filed from Uttarakhand up till the 31st of January, 2020, 6,510, or 99.85% of these claims, were disposed of.

This state of affairs is linked to how the Act has been implemented in Uttarakhand.

The Uttarakhand government notified the FRA in November of 2008. It issued an order for the establishment of sub-divisional and district-level forest rights committees, and fixed December 31, 2009, as the projected date for the title distribution of forest rights.

182 claims were filed between 2008 to 2009. But, they have either been under process or rejected citing the excuse of the model code of conduct (MCC) for elections being in force when the Act was notified. The MCC is a set of guidelines issued by the Election Commission that regulate governance during elections—this ensures no governmental activity that influences voters is allowed. It is interesting that while the State continued pursuing other governmental activities during these years, it only faced the issue of MCC in matters of forest rights recognition.

The data shows that 65% (46) of the total assembly constituencies in Uttarakhand have more than 20,000 potential FRA voters; and 27 % (19) have more than 50,000 potential voters who will benefit from implementation of FRA @ANI @INCSandesh @NewsArenaIndia @republic @timesofindia pic.twitter.com/XK0CkZ0570

— Forest Rights (@ForestRightsAct) January 25, 2022

The Uttarakhand government did not even revise the projected deadline for title distribution (2009), as is evident in the FRA status report released by the MOTA in 2017. In March 2017, with the issuing of an order by the National Tiger Conservation Authority that disallowed the recognition of rights under the FRA in Tiger Reserves, the forest rights process in Uttarakhand was violated once again. In 2017, Komal Singh, the Chief Wildlife Warden of Rajaji National Park, without complying with Section 61 of the Uttarakhand Forest Act, issued eviction notices to Van Gujjars residing in the Gohri, Chillawali, and Asarori forest ranges. However, in 2019 through Think Act Rise Foundation, the Van Gujjars challenged these illegal evictions of Van Gujjars from RNP and advocated for recognition of their Forest Rights.

Linguistic and regional politics also impact the identities of indigenous groups and forest-dependent communities. Unlike as in Himachal Pradesh, the Van Gujjars in Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh have not been awarded tribal status—instead, they are classified under Other Backward Class. This has resulted in the community being categorised as Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (OTFD) under the FRA in Uttarakhand. Under the FRA, OTFDs are required to provide two proofs of their occupation of the land for up to three generations (or 75 years). Since the Van Gujjars are a nomadic community, and migrate from location to location, producing such residence proofs is near impossible.

Additionally, in prescribing the roles of District-Level Committee, Rule 8(b) of the FRA carefully mentions, “the committee has to examine whether all the claims, especially those of Primitive Tribal Groups, pastoral and nomadic tribes have been addressed.” In this regard, rule 12(c) also ensures that the verification of claims registered by pastoral and nomadic communities for the determination of their rights must only happen when they are physically present. The bureaucratic apparatus willingly fails to prescribe and comply with the law. Although MOTA allows oral testimonies from community elders as an acceptable form of proof, as per this author’s interactions with the community, the bureaucracy refuses to accept them, ultimately resulting in rejected claims. The additional absence of any training and awareness campaigns means that the Van Gujjars have often struggled to become acquainted with the process and vocabulary of the FRA.

Despite this, the community has made significant strides in filing its FRA claims. Meer Hamza, President of the Van Gujjar Tribal Yuva Sangathan and from one of the few families that have not left RNP elaborates. “At present, 800 Individual Forest Rights [IFR] Claims of Van Gujjars from all over Uttarakhand and 17 Community Forest Rights [CFR] claims are under process at different levels,” he says. “For those living inside Rajaji National Park, we have filed 37 IFRs from Gauri Range and 9 from Ramgarh range since 2017. These are still pending at the Sub-Divisional Level Committee.”

As per a MOTA monthly progress report, the total number of forest rights claims received by the Uttarakhand government till 31 December of 2017, is 182. In January of 2018, the number of total received claims jumped to 6,665 implying 6,483 new claims filed under the FRA. The Uttarakhand government had still not processed any past claims. It was only in December of 2018 that 144 Individual Forest Rights claims and a single Community Forest Rights claim were distributed to communities living here. Even then, pattas, or certificates, were not provided to the right holders.

The impacts of this wilful non-implementation are directly felt by the Van Gujjars. On August 16, 2018, the Uttarakhand High Court passed an order for the removal of Van Gujjar families from the state’s Jim Corbett National Park, describing them as encroachers. Although an interim stay was obtained from the Supreme Court, the Uttarakhand High Court was precise in its judgement: “the Van Gujjars are a constant threat to the wildlife.” It went to the extent of questioning how the State government can contemplate any rehabilitation policy or package for those who are encroachers on land. Ironically, in July of 2018, while presiding over a PIL, the same High Court bench at Nainital, ordered “the entire animal kingdom” as legal persons and “the citizens in the State of Uttarakhand as “persons in loco parentis as the human face for the welfare/protection of animals.” The pastoralist thus fails in becoming a citizen while their grazing buffalo loses the race to the tiger for tourism.

Such instances indicate the deep-seated prejudices and bias against forest-dependent communities that inhabit the politics, the state institutions of power and even the judiciary. Yet, the transhumant lifestyle of the Van Gujjars symbolises their symbiotic and sustainable coexistence with the environment while also revealing the critical role they play in conserving Himalayan ecology. As a matter of fact, the Department’s working plans, dating back to 1952, show records of the grazing activities of the community.

“The Van Gujjars share a sacred relationship with the forest and wildlife. Deers can often be seen in large herds in and around our deras [settlements]. They come there to take shelter from predators,” explains Meer. “We need the forests as much as the forests need us Van Gujjars. We have been living together [for years].” Yet, as we see in the third and final piece of this series, such symbiosis means little to the post-colonial Indian State.

This article is based on a detailed case study compiled by the author for the Centre for Financial Accountability. The author pays gratitude and credits to Mr. Meer Hamza, President of the Van Gujjar Tribal Yuva Sangathan, a youth activist, and a resident of Rajaji National Park. The author thanks Meer for sharing their knowledge, perspectives, and critiques, and for being a great storyteller.

Featured image: a road passing through Rajaji National Park, Uttarakhand; courtesy of Kayvan126 (CC BY-SA 4.0).

[1] Taungya villages were settled here by the Forest Department to serve as labour forces for plantations and other departmental activities. The Taungya have also been dependent upon forests for cultivation. Although this piece does not cover their experiences, the Taungya have also been affected by the politics unfolding within Rajaji National Park.

[…] is a Muslim Van Gujjar from Uttarakhand. The Van Gujjars are nomadic buffalo-herders who live in the Himalayan foothills. […]

[…] colonial conservation plays out in Uttarakhand’s Rajaji National Park. Click here to read part two on how this model impacts the rights of the Van Gujjars living […]