The 2020 Union Budget has been released. With an aim to create a $5 trillion economy to push India out of its current economic crisis, it is an ambitious document. But consider this: a report by McKinsey and Co. suggested that unchecked climate change would cause a reduction of 2.5-4.5% of India’s GDP. Despite this being a scary revelation, the Finance Minister’s 2.5-hour long budget speech saw a miserly three minutes dedicated to Environment and Climate Change. When she did get around to it, she announced an allocation of ₹4,400 crores in 2020-21 to combat air pollution in cities across India.

So, when it comes to climate change finances, how exactly does India fight the big, bad phenomenon? A few encouraging developments have taken place in this context recently. In October of 2019, India joined the International Platform on Sustainable Finance, moving towards transitioning current economic investments into a green, low carbon, climate-resilient economy.

A significant development has also been the launch of the Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure in September 2019. This will promote the resilience of new and existing infrastructure systems to climate and disaster risks. It is a welcome step given that India has been ranked as the fifth-most vulnerable country to extreme weather events, according to Germanwatch, an environmental think tank.

Hon’ble PM @NarendraModi announced the Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure at #ClimateActionSummit,calling for a comprehensive approach to #ClimateChange. #CDRI will catalyse development of #ResilientInfra across the world. We invite member states to join the movement pic.twitter.com/hxNM6Ub3MM

— Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure (@ResilientInfra) September 23, 2019

In terms of tangible prospects, the Economic Survey 2019-20 boasts of approving 30 adaptation projects across vulnerable sectors like water, agriculture, forestry ecosystems, and biodiversity. In all, this cost the country roughly ₹1819 crores. But, where does this money come from? And more importantly, how well does this feature in the budget?

The Big, Fat, Green Climate Fund

Climate change financing is messy. Currently, this financing is a result of multiple processes fed by domestic funds (like the developments mentioned above) and foreign funds. An important foreign fund is the Green Climate Fund, which is the world’s largest fund created under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

You May Also Like: Shared Atmosphere, Equal Responsibility? Enter, Climate Debt

The motive behind creating the Green Climate Fund is simple. Since climate change has been fuelled by ‘developed’ countries, they should “pay”. One of the ways of doing so is by providing funds to middle-income and low-income nations for adapting to and mitigating climate change. Financing the UN’s SDGs worldwide is estimated to come at an enormous cost of $5-$7 trillion USD per year, as noted in the previous Economic Survey.

Now, in terms of the money flowing from developed countries, 2016 data reflects something surprising: of the $75 billion raised in climate funds, India received about $2.5 billion, making it the highest recipient over any other country. Then why aren’t as many mitigation and adaptation projects on the cards?

As it turns out, reports citing these estimates have been heavily criticised by many experts. In 2015, a discussion paper by Climate Change Finance Unit, a body created under the Economic Affairs Department, questioned the methodological credibility of one such report. One of the problems, it stated, was that pledges to climate funds have been a significant $32 billion USD, but actual funds deposited from those pledges to countries is almost half, at $17 billion USD.

The strong critique of inadequate funds flowing from developing countries extends in this Economic Survey too — it states that where new funds have started flowing for the years 2020-2023, only 28 countries pledged resources worth $9.7 billion USD to replenish the fund. This, it states, is quantitatively lower than 2014, but by how much, it doesn’t say.

So, if the foreign flow of money into India or any other developing country for that matter is debatable, then what does our domestic fundraising for climate change look like?

A Look into the 2020 Budget

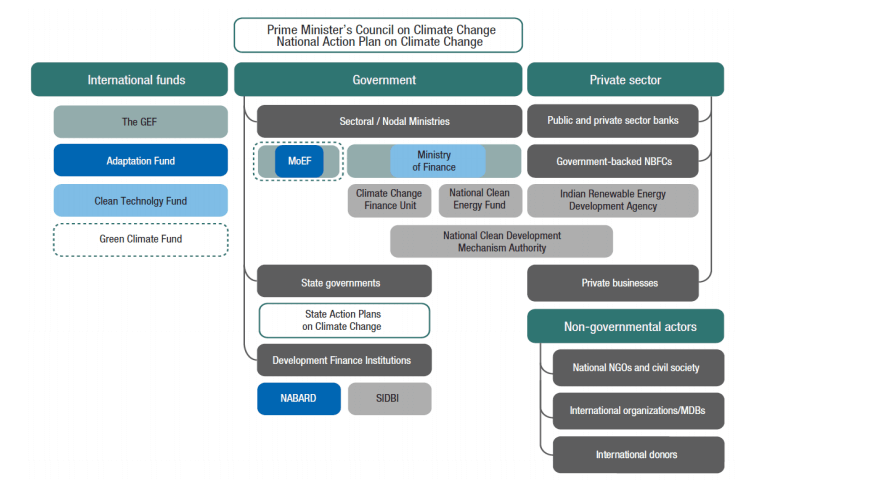

Currently, climate financing in India is a result of multiple processes and institutions, which include, ministries and departments within the government (like the Prime Minister’s Council of Climate Change), local and sub-national entities (state governments), development finance institutions (NABARD), public sector banks (SBI and Canara Bank), private sector banks (ICICI, HDFC), and civil society organisations or NGOs (TERI, CSE, although not through direct financing).

Sounds complex? That’s because it is.

Apart from these bodies, climate change fund-raising can be seen in fragmented ways through some schemes across departments. Let’s have a look at how they fare in this year’s budget.

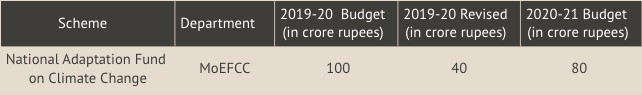

In 2015, India created a National Adaptation Fund on Climate Change to support concrete adaptation activities for states and UTs that are particularly vulnerable to adverse effects of climate change, and are not covered in the ongoing schemes. This was to end in 2020, but has been revised for 2020-21. Not only does this form a very small 3% of the total funds allocated to MoEFCC, but this budget also reveals something discouraging: not only did 60% of the budgetary allocation remain utilised, but the budgetary allocation for this year has fallen by ₹20 crores!

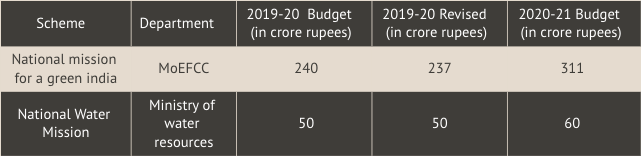

Some more schemes and budgets have been bought under the umbrella of fighting climate change. These were termed as the National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC). Launched in 2008, it enveloped 8 schemes within it. States and Union Territories were to follow suit and create state action plans on climate change in line with its mandate.

Of these 8 schemes, only two feature in the 2020 budget document, which could either mean that these schemes have been subsumed by other schemes, or that they have not been allocated any funds. As for the two that feature, namely the National Water Mission and Green India Mission, the picture looks more reasonable:

While all of the budget sanctioned for the National Water Mission was utilised, 3% of the budget allocated for the National Mission for a Green India remained unutilised.

As you must have got the sense by now, there are too many actors involved in India’s climate change finance infrastructure. This, of course, means that a coordinating mechanism is needed. The saviour of climate change finance then came in the form of Climate Change Finance Unit (CCFU).

The CCFU Way Forward

Formed under the Department of Economic Affairs of the Ministry of Finance, the CCFU was to be the nodal agency to integrate climate change into development frameworks and financial systems while supporting sustainable development and mitigation plans. But, over the decade, its role has been limited to representing India in international conferences. A press release by the Ministry of Finance in 2018 makes this clear:

As the nodal point for Climate Change Finance matters in the Ministry of Finance, CCFU has been representing the government of India in various international fora…

This means that we are staring at a climate change crisis without any strong institutional, coordinating mechanism in place.

The budget over the years has been disappointing in terms of financing mitigation and adaptation strategies, and 2020-21 is no different. There may be more schemes and policies that can be attributed to fighting climate change indirectly, but the real challenge lay in our fragmented approach. Climate change has been resigned to the margins through piecemeal policymaking and is far from the mainstream.

It has been suggested that a ‘Statement on Climate Change’ be released within the Union Budget, which could state all the climate-relevant budgetary allocations of multifarious departments. Denmark introduced something similar last year.

Big news on climate change in the EU, with France, Belgium, Denmark, Luxemburg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and Sweden drafting a proposal to spend 25% of EU budget on climate change, and net-zero greenhouse gases for the EU by 2050https://t.co/M8F0lNb2It

— Dominic Andersen-Strudwick (@AndersenDominic) May 8, 2019

If financing the fight against climate change through mitigation and adaptation is not taken seriously, the push towards creating a $5 trillion USD economy is going to come at a grave environmental cost. Maybe I need to put this in a way that would sound appetising to the shloka-chanting Hon’ble Minister of Finance:

क्लाइमेट चेंज इस रियल्| एलोकेट मोर बजेटम:!

Featured image courtesy Markus Spiske on Unsplash

[…] is seemingly one of the largest beneficiaries within Asia; the yearly average for climate finance flows in 2015 and 2016 was […]

[…] is seemingly one of the largest beneficiaries within Asia; the yearly average for climate finance flows in 2015 and 2016 was […]

[…] is seemingly one of the largest beneficiaries within Asia; the yearly average for climate finance flows in 2015 and 2016 […]

[…] You May Also Like: Budget 2020: How well is India financing its fight against climate change? […]

[…] change is real. And that calls for real, deserving funds to be diverted towards mitigation and adaptation projects. But, as a report of the Ministry of […]

[…] You May Also Like: Budget 2020: How well is India financing its fight against climate change? […]

Very informative, nicely written article, Congratulations, do share some information on financing of climate changes, My husband is working on solar and has installed many plants. The only problem is that companies, Housing societies get solar installed but DO NOT make the full payment. I feel government should take some initiatives in this regard. Even the government undertaking do not make payment in time, thats create a problem for solar companies.