Environmentally speaking, a lot of developments—and disasters—marked the months of 2021. The year began with fisher communities and ecological experts opposing a ‘Mega Ecotourism’ Project in Manipur’s famous Loktak Lake. In February, rocks and snow cascaded down the slopes of Uttarakhand’s Chamoli. Creating one of the worst flash floods in the state’s history, the event was caused by “heavy snowfall” after “unusually warm weather” in the region. Three months later, Goa and the rest of India’s western coast tackled the devastating cyclone Tauktae, and by the time the monsoon arrived, 24 districts of Uttar Pradesh (UP) were partially underwater due to heavy floods. Come October, the burning of agricultural stubble by farmers in Punjab—and its contributions to deadly air pollution across northern India—once again made headlines.

Starting in February 2022, these five states—Manipur, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, and Goa—will be heading to the polls for their respective legislative assemblies. Considering that the ecological impacts of climate change and other environmental conflicts need no introduction in these states, how have contesting parties been talking ‘green’, if at all? Why do rivers often become the centre of all things environment in the manifestos? How different are the promises being made from previous campaigns in the 2017 Assembly elections?

The Bastion analysed the election manifestos released in these five states in 2017 by the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), Indian National Congress (INC), Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), Samajwadi Party (SP), and Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD). Since the manifestos for the upcoming elections were not publicly available at the time of writing this article, we observed parties’ Instagram handles* from December of 2021 until the last week of January of 2022 to see how issues surrounding the environment feature in their political campaigning. The Bahujan Samaj Party—one of Uttar Pradesh’s biggest political parties—has been left out of this analysis as it did not release a manifesto in 2017, and its social media does not currently mention any promises for the 2022 Assembly elections.

Despite the environmental and climate issues plaguing these five states, policies and promises that even address these concerns seem few and far between. The Bastion found that in the selected manifestos, sections dedicated to the environment found little importance —appearing only after 70-100%** of the manifesto discussed employment, education, and corruption. The only exception was the BJP’s 2017 manifesto for Manipur, where ‘Sustainable Development’ arrived sooner in the discussion, some 37% into the manifesto.

“India’s political atmosphere is still not developed enough yet to make the environment a key poll agenda,” says Hrid Bijoy, a volunteer and researcher for the Aam Aadmi Party. “We know that environmental concerns are not yet issues that will bring us votes. So, we usually focus on environmental policies like replacing polluting fuels with Compressed Natural Gas and [popularising] electric vehicles, [both of] which are directly connected to people’s health.” Apart from health, in the Instagram campaigns and manifestos surveyed for the 2017 and 2022 Assembly elections, environmental concerns are also complemented by promises of heavy infrastructural development and revived cultural identities.

When the Environment and Infrastructure Go Hand-In-Hand

Across political parties, the environment finds a mention in a manifesto sub-heading here, or in an Instagram post there. But, whenever it does appear, the environment is almost always partnered with infrastructure projects. For example, in an Instagram post for the 2022 Assembly elections, the BJP’s Uttarakhand wing promises to launch a ₹1,200 crore tourism project on the popular Tehri lake—the Tehri Jheel Vikas Yojna—while its counterpart in UP promises drinking water for every house. The trend repeats itself with the Samajwadi Party’s commitment of free electricity for irrigation in Uttar Pradesh recently advertised on Instagram.

This trend of featuring the environment largely in the context of infrastructural development appears in the 2017 manifestos as well. In Uttar Pradesh, the BJP promised to build sewage treatment plants on the banks of the Yamuna and Ganga, as well as to set up a Chief Minister’s Irrigation Fund with separate funds allocated for the drought-hit Bundelkhand region. In Manipur, the revival of inland waterways also drew a mention in the BJP’s manifesto.

Looking at voter priorities can indeed explain why infrastructural development continues to find so much space in manifestos and campaigns. When the Association for Democratic Reforms surveyed over two lakh respondents for an all-India survey on voting behaviour in 2018, they found that better employment opportunities, hospitals, drinking water, roads, and public transport systems were the top five governance issues that voters prioritised. Further down the list was the availability of water for agriculture and agricultural loans. These priorities mirror the poll agendas that the BJP and other large political parties tend to focus on.

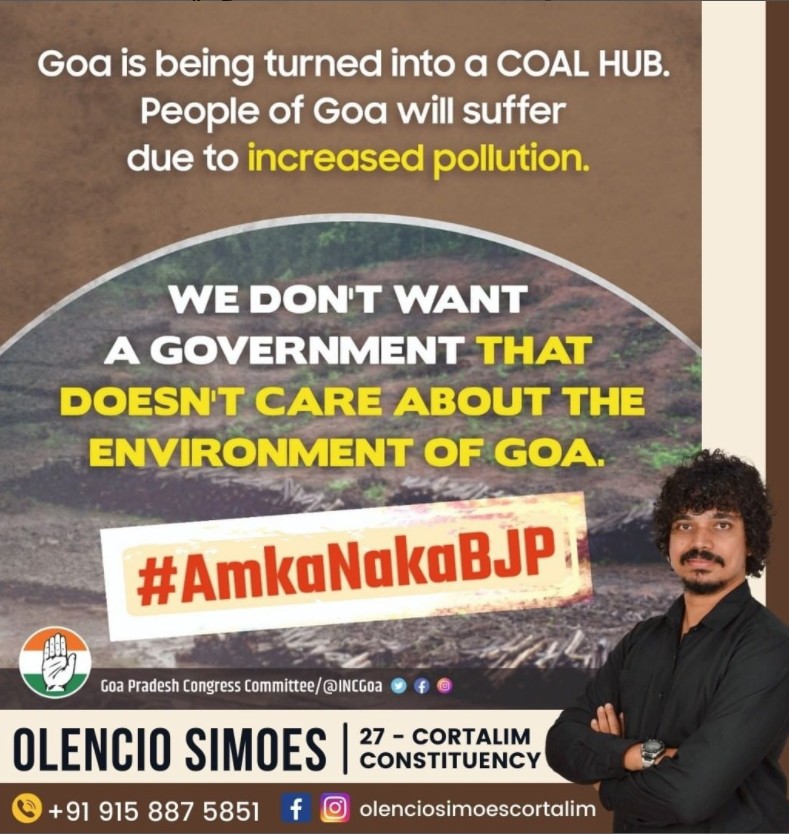

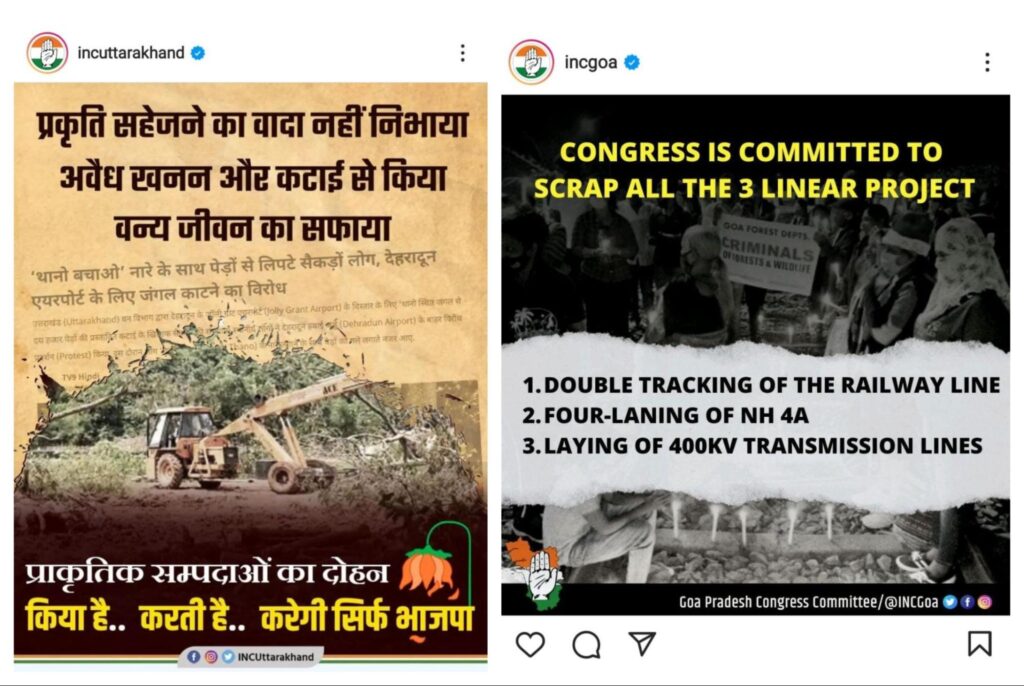

Interestingly, for the 2022 Assembly elections in Goa, the Indian National Congress stands at the other end of this infrastructure-heavy spectrum, highlighting the environmental damages due to massive development projects. The INC’s manifesto promises to scrap the three linear development projects issued by the Centre cutting through Goa’s Mollem forests—which include a railway line, a highway, and power transmission lines. Protests against these projects became the heart of the people-led Save Mollem movement in 2020.

“Olencio Simoes, who belongs to the fishing community, is contesting from south Goa’s Cortalim for the INC. He has been very vocal about issues like [development projects in] Mollem and the Coastal Regulation Zone amendments, and has played a huge role in mainstreaming them in the INC’s campaigns in Goa,” says Sarita Fernandes, a coastal policy researcher. “We saw that the INC was interested in environmental concerns of the state this time, which is why Ruhi, Radhika [both from different climate and environmental movements], and I submitted a youth manifesto to Priyanka Gandhi [a senior Congress leader] in January.” The manifesto was submitted during the INC’s consultation with NGOs in the state.

In Uttarakhand too, many of the INC’s Instagram posts for the upcoming Assembly elections are dedicated to illegal sand mining and forest fires in the state, while also commenting broadly on its environmental degradation. For example, on Instagram, a post decries the “exploitation of natural resources…BJP is doing, has done, and will continue doing”. The background of the post is a newspaper clipping about “Save Thano”, a youth-led protest in Uttarakhand agitating against the cutting of trees for Dehradun’s airport expansion.

Beyond a Natural Resource: Rivers, Religion, and Identity in Uttar Pradesh and Punjab

On Instagram last week, the BJP posted a video from Uttar Pradesh, where the rivers Ganga and Yamuna emerge widely, flowing along the banks of temples, into canals between highways, and under dams. A deep-voiced narrator binds the video together, saying “vachan diya hai humne Maa Ganga ko…vachan diya hai humne poore UP ko [we have promised Mother Ganga, we have promised the entire state of UP”]. The promise in question: that the ruling BJP will return to power once more in the state, ostensibly off the back of the strong cultural ties surrounding the river. In other videos and reels on its Instagram page, viewers catch a glance of the Ganga and Yamuna, on whose waters boatmen proudly hold the BJP’s flag.

Although these images are not direct electoral promises to develop river-related projects, they play an important role in evoking a sense of a collective identity for Hindu voters in Uttar Pradesh who associate with the Ganga and Yamuna’s religious connotations.

Political Scientist Mukul Sharma has written about how certain environmental features—including rivers—can become metaphors of specific religious practises and mythical beliefs, which are then mirrored in Hindu nationalist rhetoric. While writing on the popular struggle against the Tehri Dam in Uttarakhand’s Garhwal in the 1970s and 80s, Sharma mentions the significant role that metaphors played in the rhetoric espoused by “environmentalists and socio-cultural leaders”. The Ganga was a holy river, with a “glorious past” recorded in the Vedas and Mahabharata—all of which would be compromised by the project’s plans to dam the Ganga and interrupt its flow.

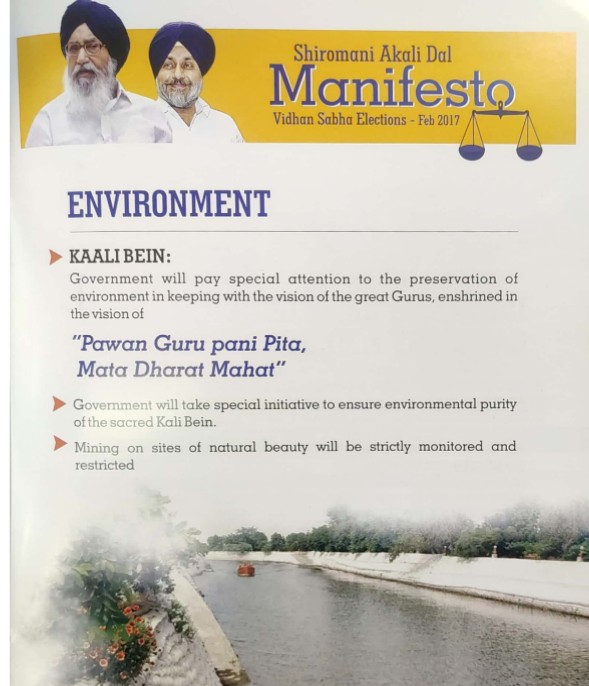

In the 2017 Assembly elections, the BJP’s UP manifesto seems to evoke similar sentiments, since Namami Gange—its flagship project to manage the Ganga’s pollution—has a separate section of its own apart from the other broad section titled “environment”. In Punjab, the SAD-BJP alliance’s 2017 manifesto also combines spirituality with the environment, stating that the government will focus on the environment “keeping with the vision of the great Gurus [of Sikhism]”, and “will take special initiative to ensure environmental purity of the sacred Kali Bein,” a river in the state.

In Punjab however, rivers became a point of discussion for political parties for distinct reasons. In 2017, both the Indian National Congress and the SAD-BJP alliance in Punjab strongly focussed on “Punjab Da Paani, Punjab Vaaste” [Punjab’s water is for its people only]. The slogan demands that Punjab’s rivers are protected under the riparian principle—which is when “the right to the use of water resides in the ownership of riparian lands (..) [or] property that borders the water body.” With this, both the INC and SAD-BJP took a strong stance on the long-contested Satluj-Yamuna canal dispute between Haryana and Punjab, assuring the electorate that they would not allow its construction to go ahead, or for the sharing of water between the two states.

By using terms like “Punjab da paani”, and demanding the recognition of the riparian principle, political parties evoke questions of territoriality, building upon Punjab’s identity of being intrinsically linked with the state’s rivers. This sentiment perhaps resonates with voters from a state whose name is derived from the five rivers that flow through it—the Beas, Satluj, Jhelum, Ravi, and Chenab (“Panch” means five and “ab” means water). Such sloganeering resonates with development scholar Jeremy Allouche’s theory of “water nationalism”, where water resources “can take on symbolic and imagined aspects of a nation state’s collective territorial sovereignty and geographic identity.”

Whether rivers will become talking points in the much-awaited 2022 manifestos is yet to be seen, but so far, at least on Instagram, rivers are not being described beyond their symbolic cultural and religious roles. Another term that seems largely—and obviously—missing is climate change.

Talking About “Climate Change” Without Actually Saying It

Despite being a longstanding and critical environmental issue in all five states, the term climate change does not appear in any of the 2017 manifestos, or in any party’s social media posts in 2022. But, the impacts of climate change have not been completely lost on political parties. For instance, in the 2017 Assembly elections in Uttarakhand, the INC raised the issue of out-migration from the state, which studies now show is connected to climate change.

“In Uttarakhand, climate change is manifesting in different forms of precarity [for people and the environment], [ranging] from changing precipitation, to shifting land use, to out-migration. Questions of employment and livelihood are very entangled with climate change, but as a term itself, it has unfortunately not become popular [in election campaigns],” says Rahul Ranjan, a postdoctoral researcher with Oslo Metropolitan University studying riverine rights in India. “Moreover, since the majority of Uttarakhand’s voters live in the plains, politicians often slump plain and hill identities together by assuming that the [environmental] demands of plains would be the same for hill populations. It’s not surprising then that not enough representation of concerns from the hills make mention in [the state’s] manifestos.”

In 2017, both the BJP and INC mentioned better disaster management in their Uttarakhand manifestos. Some more instances of climate change impacts also showed up that year—be it in the BJP’s promise of desilting canals in UP to prevent floods, its plans to map flood areas along river valleys and landslide zones in Manipur, or the AAP’s commitment to compensate crop losses due to droughts, floods, pest attacks, and unseasonal rain in Punjab, all of which are influenced by a changing climate. But, similar pledges are not very visible in 2022 on their social media pages, except in Goa, where only the INC so far has spoken about providing support during floods.

“We [the AAP] are slowly working to ensure transparency and accountability [regarding environmental degradation]. This is seen in the Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal tweeting Delhi’s poor AQI measures throughout the winter season. While we believe that we focus more on the environment than the other parties, we do not deny that all of us [political parties] have to work harder to bring ‘environment’ onto the political radar,” adds AAP’s Bijoy.

So far, political parties have incorporated the environment into their campaigns and manifestos riding on to the sentiments that voters associate with—religion, territoriality, and infrastructural development. Yet, while the impacts of climate change are also slowly finding ways into poll agendas, they seem to be far from prioritised for both voters and political parties, an unfortunate case for Goa’s mangroves, Uttarakhand’s forests, Punjab’s riverine ecology, Manipur’s floating islands and fishers in Loktak, and Uttar Pradesh’s rivers.

Featured image: an Aam Aadmi Party rally held in Punjab in December of 2021 in the run up to the state’s legislative assembly elections; via Arvind Kejriwal on Twitter.

* Instagram was analysed because other popular social media platforms like Twitter and Facebook respectively allow for retweets and sharing on individual accounts. This made it difficult to tease out when the parties themselves were posting, or when they were sharing someone else’s post—something that did not happen on Instagram.

** The author calculated this on the basis of what section the “environment” subheading appeared in across all sections. For example, if the environment was the 40th section in a manifesto with a total of 49 sections, that means the environment-specific section appears in the manifesto after 81% of it has been read.