Much of my refuge during last year’s winter was spent in the pages of Amitav Ghosh’s latest book, Gun Island. A character who stands out in it is the quirky, opportunistic teenager Tipu from the Sunderbans in West Bengal. Armed with the internet and a phone, he is a part of the circuit that helps people migrate from Bangladesh to Europe, in the hope of a better life. Through the course of the novel, he himself becomes a refugee, and reveals harrowing accounts of the mental and physical turmoil that accompany his migration across the territories of Pakistan, Iran, and Turkey.

Tipu, in a conversation, also reveals the reason for this accelerating exodus: “Now the fish catch is down, the land is turning salty, and you can’t go to the jungle without bribing the forest guards. On top of that every other year you get hit by a storm that blows everything to pieces. So what are you supposed to do? What would anyone do…even the animals are moving.”

The novel sounds scary, doesn’t it? But here is the scarier part—these experiences today do not belong only to fiction: climate change migrants, whether domestic or international, are a reality of our times.

In fact, the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre has calculated that worldwide, climate-related disasters have triggered 17.2 million displacements in 2018. Of this, 60% of all new displacements were accounted for by the Philippines, China, and India, mostly in the form of evacuations.

Extreme Weather Events

Much of this kind of migration is being triggered by extreme weather events. While the world witnessed 286 and 228 extreme weather events in 2018 and 2019 respectively, India alone recorded 23 in 2018 and nine in 2019, as the State of India’s Environment 2020, a report by the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) reveals. These events have ranged from a 44% deficit in rainfall, to an extreme cold and dry winter, to unseasonal heatwaves.

More unprecedented events followed—between October and December, eight cyclones, like Hikaa, Kyarr, Maha, Bulbul, and Pawan, occurred making this the highest number in a single year since 1976.

What is even more astonishing is that in the 148 countries where 28 million people were internally displaced, a large proportion of them, around 61%, were displaced due to disasters. This weighs much heavier than the 39% who were displaced due to conflicts and violence, as the State of India’s Environment reports.

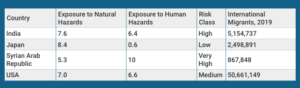

Additionally, the World Migration Report 2020 released in November last year ranked countries on a scale of 0 to 10, based on the likelihood of their being affected by either natural or human hazards. For natural hazards, India was ranked 7.6, while for human hazards, it bagged a rank of 6.4. Overall, with over 5 million international migrants recorded, India was labelled under the ‘High Risk Class’. The indice, based on the vulnerability of the country, also acknowledges countries’ capacities to respond to climate change, on the grounds of quality of the infrastructure and accessibility to healthcare.

But, where is the Data?

Undeniably, increasing extreme weather events have changed the reasons behind migration; but even now, finding data on this relationship is a difficult task. In India, no such efforts have been made yet to pit migration data against the disasters occurring, as well as the poverty levels of the state. But, looking closely at the changing weather conditions in migration hotspots of the country shows that natural disasters too, could be a key factor of this push.

Take, for instance, the Bundelkhand region shared between Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh. Here, the migration rate-or the number of migrants out of the total population-is as high as 28% in some parts. The Census usually cites employment, business, education, and marriage as reasons for the increase in this migration. But consider this: around 60% of the region’s main workers-those who work for 6 months or more in a year- are engaged as cultivators or labourers. More importantly, agriculture here is mostly rain-fed.

Now, the trends of extreme droughts have shown an increase. From one every 16 years during the 18th and 19th centuries, they increased by up to three times between 1968 and 1992. It has also been reported that in the last 13 years, there has been a reduction in the annual average rainfall in the region by as much as 40%, with a 60% reduction measured in the last five years. However, trying to establish a link between migration from Bundelkhand because of a changing climate is still an exercise yet to be carried out by the government.

Many villages in Bundelkhand have emptied out as lengthening drought becomes a new normal. The Govt has been ineffective in providing remedial measures to the aggrieved farmers. pic.twitter.com/KFd6edSOLN

— Congress (@INCIndia) July 9, 2018

Another complication is obtaining reliable numbers on migration when it is not forced. As the World Migration Report 2020 states, it is difficult to compute reliable estimates for the numbers of people moving in anticipation of or in response to slow-onset processes like desertification or rising sea levels.

Umi Daniel, the Director of Migration and Education at Aide et Action International told The Bastion, “There is a high need for better collection of data. In fact, sometimes, people are moving from one storm hit state to other highly vulnerable states like Tamil Nadu and Kerala. These migrations also need to be recorded.”

So, what are the impacts of not having recorded data? Binod Khadaria, the co-editor of the World Migration Report 2020 explains, “Data on this type of migration is coming from the countries who are receiving the migrants, not from those where the migrants come from. The data is not very helpful when trying to forecast migration prone populations.” In other words, it becomes difficult for those living in disaster-prone areas to plan preventive measures against disasters that follow a repetitive pattern. This hinders preparedness.

Are We Prepared for the Worst?

“There is a need for a long-term strategy to deal with climate change resilience,” says Daniel. “A risk-informed approach to development programs is something that I have suggested. This would ensure that development decisions are taken based upon climate risks, resulting in more sustainable and resilient projects.”

You May Also Like: Budget 2020: How well is India financing its fight against climate change?

There is also a lack of investment and funds for building resilience. Daniel has also been studying the budgets sanctioned to Odisha. Despite the number of storms that Odisha has faced, the state still does not receive enough money to deal with it.

One way to use existing funds is to utilise schemes like the National Rural Employment Guarantee Program (MGNREGA) to create climate change resilient assets in high-risk areas. Since MGNREGA permits the construction of structures for water harvesting, drought proofing, and flood control amongst others, these can help mitigate and adapt to climate change.

An administrative establishment would help to make these migrations smoother. For instance, in the case of inter-state migrants moving for employment, the State Labour Departments of the Governments of Odisha and Andhra Pradesh have signed MoUs with the Government of India. This has helped both states formulate a time-bound and result-oriented action plan to benefit migrant workers. “Moving from one state to another is, after all, a fundamental right,” continues Daniel. “It needs to be made flexible and smooth for the migrants. Similar government agreements like the MoU between states can offer convenience to even climate change migrants.”

People have always migrated, but now they are migrating because of climate change. Without studying this phenomenon, collecting data and proactively creating resilience, India might be heading for a future where we are neither hoping for the best, nor preparing for the worst.

Featured image courtesy of John Englart (CC BY-SA 2.0).

[…] You May Also Like: Leaving Homes Due To A Climate Crisis […]