It was 1979 and the monsoon was in full swing in Gujarat. The continuous rain, an overflowing Machhu river in the western parts of the state, and crucial decisions by the operators of Machhu II Dam were about to create India’s worst dam disaster. The dam was functioning close to its full capacity of 200,000 cubic feet per second, and all its gates were opened to keep the water collecting in the reservoir from overflowing.

Yet, with the incessant rain, water did overflow. It violently cascaded into the villages of Lilapur and Morbi, consuming everything in its way—lives, properties, and fields. The exact number of deaths caused by the Machhu II Dam remains murky till date—before records were taken, mass burials were held to prevent the spread of diseases. Estimates range from 1,800 to a colossal 25,000 lost lives. And yet, who was responsible for the disaster—whether it was the poor design of the dam that underestimated the monsoon’s flow or the dam’s operators— still remains contested.

42 years after the Machhu Dam II disaster as well as other similar events in Kerala and Himachal Pradesh, the Dam Safety Bill, 2019 was passed in the Rajya Sabha on December 2, 2021. The Bill’s aim: to enforce safety and accountability measures, and to ensure the maintenance of dams. To do so, it draws out a two-tier organisational structure and set of functions for the “surveillance, inspection, operation and maintenance of dams for prevention of dam failure related disasters.” A game changer clause within the Bill has been the introduction of penalties and offences in cases of non-compliance to dam safety.

“When a dam breaks, it’s not just humans that get impacted, but also the entire riverine ecology,” Gajendra Singh Shekhawat, Minister of Jal Shakti said while presenting the Bill in the Parliament, adding that accountability for such disasters could now be better identified. But, not all present in the upper house of the parliament agreed with the Bill. Opposition parties ranging from Tamil Nadu’s All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam, to the Indian National Congress in Gujarat, to West Bengal’s All India Trinamool Congress debated against it, calling it an “infringement of [a] state’s autonomy” since the Centre was deliberating on rivers, a subject primarily listed on the ‘state’ list, while also alerting towards the Bill’s other drawbacks.

More #Dam or Damage? Despite the collapse in Laos, 3,500 more #hydropower dams are being built around the world, @BBCWorld reports. India & Nepal, the source of Bangladesh #rivers, are in top 10.@riverine_people @Indian_Rivers @intlrivers @fishmigration https://t.co/vlda1JoZm6 pic.twitter.com/8BsWa7ZnrH

— Sheikh Rokon (@skrokon) August 6, 2018

Yet, India is home to 5,700 large dams, 80% of which are already over 25 years old, while 227 dams are over 100 years old and are still functional. Since independence, 42 dams in India have collapsed. This indicates the urgent need for a mechanism to oversee the functioning of dams and prevent damages to them that can turn into disasters. So, how far does the new Dam Safety Bill do this?

A Central Decision For A State Subject

This Bill spent 34 years in the mill before it was passed in the Rajya Sabha this December. Post the Machhu II Dam disaster, a Standing Committee was constituted in 1982. In 1986, their report suggested institutional arrangements for dam safety. Following this recommendation, a draft Bill was prepared by the Central Water Commission (CWC) the next year. The Bill was first introduced in the Lok Sabha in 2010 by the Indian National Congress, after which it was referred to a Standing Committee on Water Resources, which recommended a few changes to it.

Through the years of India’s independence, a major point of contention for states has been that of the Centre making decisions on state subjects. Legally speaking, to allow the Centre to legislate on a state matter, the Bill brought the legislation under Article 246, to be read with Entry 56 and Entry 97 of the Constitution’s Union List. Together, these allow the parliament to create laws on any matter under List I, make laws on inter-state rivers and river valleys in the public interest, and legislate on any other matter not present in either List II (the State List) or III (the Concurrent List), respectively.

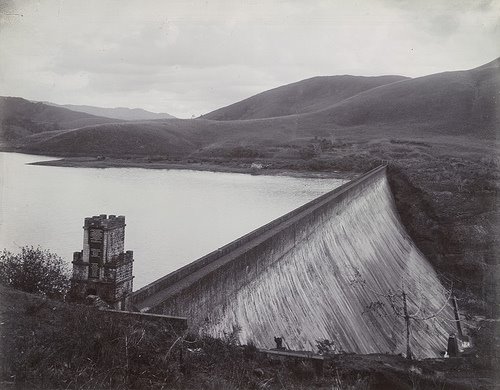

Responding to the states’ concerns, Jal Shakti Ministry’s Shekhawat addressed the Rajya Sabha, saying, “92% of the dams in India are on inter-state rivers, and it is only in these cases, the centre [sic] would intervene.” One such contested dam is the 126-year-old Mullaperiyar dam, which is situated in Kerala but operated by Tamil Nadu. The dam has produced years of legal disputes between the two states on questions of who controls it. Additionally, the dam has far outlived its intended 50 years of life, has structural flaws, and continues to operate in a seismically active geography, which could impact lives of 50 lakhs residents downstream in Idukki in case of the dam breaking.

“For decades, no decision was taken [by states] on contentious issues like the Mullaperiyar Dam because it involved lengthy court cases whose verdicts also ended up exacerbating the issue rather than solving it,” Dean Kuriakose, a Member of Parliament from Idukki, tells The Bastion over email. “Even when Kerala has reiterated its commitment to give water to Tamil Nadu, a solution that guarantees safety to Kerala was never found. Now [with the Bill], the Centre would be in a position to take a call in situations like this. If the Centre takes a good decision, these issues can be solved instantly,” reiterated the Indian National Congress Member.

Also Read: The Risky Business of Large Hydropower Dams

However, Himanshu Thakkar, co-ordinator at SANDRP, believes that the guarantee of states’ autonomy could have been made explicit in the legislation. “While it is necessary to have a national-level body to deal with issues of dam safety, the Bill could have been more carefully drafted to ensure states’ autonomy will be maintained, except in cases of inter-state dams,” he explained over a telephonic interview with The Bastion. These finer points are currently missing from the Bill.

In a bid to secure accountability in the case of dam disasters like that of Machhu II Dam, the Bill introduces a set of punitive actions for non-compliance with dam safety. What are the hits and misses of such a justice system?

Penalties, But No Compensation

The addition of punitive action is owed to the Standing Committee’s report of 2011, which was submitted after the Dam Safety Bill was first tabled in the Lok Sabha back in 2010. In it’s 2010 avatar, the Committee found no mention of penalties imposed on dam owners or anyone else responsible for dam failures that cause disasters upstream and downstream of the dam. Incorporating this suggestion, the Bill now makes obstructing the work of the National Committee on Dam Safety and other national and state level dam safety authorities refusing to comply with their directions a punishable offence, tantamount to imprisonment for up to two years and a fine. Moreover, the Bill also holds neglected dam safety by government departments and companies as a punishable offence, the penalties for which will be decided “accordingly”.

But, the new legislation misses out on a crucial aspect. “The Bill does not talk about compensation for the people who might get impacted by dam-related accidents,” Thakkar says. The only mention of compensation is under the functions of the National Committee on Dam Safety who aim to “explore compensations, by means of insurance coverage for the people affected by dam failures.”

Dozens of villages in #Kerala are grappling with catastrophic floods after heavy monsoon rains and dam releases in August. https://t.co/cu9xSZhVer #India #Sentinel2 #Landsat #KeralaFloods pic.twitter.com/fbS3UTBDxN

— NASA Earth (@NASAEarth) August 25, 2018

The absence of legal provisions for compensation leaves impacted people with the only option of approaching courts, which does not always lead to desired results. In a 1997 dam disaster in Gujarat’s Aravalli district, water released by dam operators of Mazum Dam damaged berry trees spread over 8 bighas of land, destroying the livelihood of the families that owned them. The families took the matter to the Court in 1998, seeking a compensation of around ₹21 lakh. The final judgement came 23 years later, where the Supreme Court awarded a much lesser compensation of ₹5 lakh to the petitioners. “The mention of compensation should have been legally mandated in the Bill,” Thakkar argues.

The Bill also seeks to establish a new organisational architecture to ensure that standards of dam safety are maintained and dam disasters are prevented. But a deeper analysis suggests drawbacks to this structure.

Is This Two-tier Structure Old Wine In A New Bottle?

The Bill mandates the formation of a think tank of sorts with the “National Committee on Dam Safety”. This organisation would act as a space to exchange techniques and approaches to safety evaluation, and to set standards for operation and maintenance practices, amongst other functions. Its implementing agency would be the National Dam Safety Authority, who would work in coordination with state Dam Safety Authorities.

But, these structures evoke a sense of déjà vu. In 1979, the same year of the Machhu II Dam disaster, the Central Water Commission (CWC) had already put in place a similar institution—the Central Dam Safety Organisation. Through its guidelines, it encouraged states to create state-level and project-level Dam Safety Cells and work along the dam safety inspection guidelines and literature created by the CWC.

But, Shekhawat spoke about what would be new in this structure when the Bill was passed earlier this month. “This Bill reiterates the two-tier system that already existed in India for dam safety,” Shekhawat had said in the Upper House. “But, [earlier] these organisations worked only as an advisory role…now, they will also have the power of imposing penalties and being accountable for their functions.”

Kuriakose agrees. “In the last week, we witnessed a faulty operation of the Mullaperiyar Dam when the shutters were opened repeatedly in the middle of the night. This caused flooding downstream and caught people by surprise. This shows that not all is well with the current management [of dam safety]. It is also now well known that the Kerala floods of 2018 was exacerbated by the mismanagement of dams, proving that if we have Dam Safety Cells, either they don’t operate, and if they do, they don’t operate in a scientific manner,” he states.

Also Read: The Dibang Debacle: Hydropower and Altered Flow Regimes in the Dibang Basin

Evidence from a dam accident in Himachal Pradesh’s Kinnaur in 2018 reflects the same operational woes, when water from Kashang Stage 1 Hydropower projects was released without warning. Upon inquiries viaRight to Information applications, Himdhara Environment Collective found that no state or project-level Dam Safety Cell existed. Instead, after the disaster, the operator of the dam formed an ad-hoc team to investigate the disaster. This team, Himdhara had found, consisted of engineers from Shongtong Karcham Hydro Project, which is another dam functioning under the same operator, indicating that the company became the “investigator of its own crime.” It turns out that the 2019 Bill too leaves space for such a nexus.

Many Conflicting Interests

In 2011, a similar conflict of interest caught the Standing Committee’s eye while going over the 2010 draft of the Bill. The Committee noted that the Bill provided for “comprehensive dam safety evaluation” of each dam through either the owner of the dam, or through their own engineers, or by an independent panel of experts. “Any member who is in any way directly or indirectly connected with the maintenance or ownership of the dam at any stage should not be associated with the evaluation of the dam safety,” the Committee had rightly recommended. Heeding this suggestion, the 2019 Bill now allows only an “independent panel of experts” to evaluate dam safety.

Unfortunately, some space for overlapping interests still exists in the newly passed Bill, something that did not go unnoticed in the 2021 Parliamentary debate. “There is something known as ‘check and balance’,” Shakti Sinh Gohil, from Gujarat’s Indian National Congress, argued in the Rajya Sabha. He pointed towards the fact that according to the Bill, the ex officio Chairperson of the National Committee on Dam Safety would be the Chairman of CWC. “How is it possible that the authority responsible for approving dams’ design is also the one handling its safety? There is an idiom,” he continued, “mei hi chor, mei hi kotwal, mei hi nyaydhish [I am the thief, the police, and the court]. That is not correct.” Gohil is suggesting that the CWC would be responsible for approving dams’ design, and also analysing causes of dam failure—which could have been due to the designs they approved.

“There is also a lack of independent voices of NGOs, and there is no representation of those people whose lives are unsafe because of such dams. Dam safety is not just about technicalities alone, it is also about the public’s interest,” Thakkar added. A look at the Bill confirms this. Both the state- and national-level committees and organisations are composed of a range of engineers, hydrological experts, and representatives from the CWC, and Central Electricity Authority amongst others. People living in proximity to dams are yet to make the cut.

“We have mechanisms like Gram Sabhas which will be in a better position to convey the anxieties of people who live downstream. My request is to make sure that high-tech instrumentation along with local consultation and responsive governance is given top priority,” Kuriakose adds.

The Dam Safety Bill, 2019 is a legislation that for the first time incorporates accountability for dam disasters, while putting in place a mechanism to prevent such accidents due to negligence or shoddy construction. However, its efficiency—as is the case with all policy making—will be tested in the ability of responsible authorities to implement its provisions both in letter and spirit. The more difficult task would be to address the limitations that exist in the text of the Bill—such as the lack of people’s representation and space for overlapping interests. These are matters that perhaps states can pay more attention to as the legislation begins implementation.

Featured image: Mullaperiyar Dam in the 1900s; courtesy of Horatio Kitchener.