On 23 April 2020, the Forest Advisory Committee (FAC)—the panel under the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change that approves forest clearance for projects—had listed 12 agendas for the day’s discussion. Third of this list was the 3097 MW Etalin HydroElectric Project in Dibang Valley, Arunachal Pradesh. Since the Project coincides with a mega-biodiversity region, much of the discussion during the meeting was around its environmental feasibility.

Then, just before closing the agenda, the FAC sought input from the Ministry of Power: what is the project’s financial feasibility, it asked, considering that India’s current demand for power might have changed since the project’s initial proposal in 2014. The Ministry is yet to respond.

₹25,296.95 crores. This is how much the Etalin project will cost the exchequer. “This is about Rs 8 crores per MW,” says Shripad Dharmadhikary from Manthan Adhyayan Kendra. “Now, if the scheduled commercial operation date gets delayed to 2027, the [total] cost would increase up to ₹33,000 crores.” These estimates were made by Dharmadhikary and researcher Ashwini Chitnis recently as a part of their submission to the Ministry of Power regarding the project’s economic non-viability.

Bharat Rohra, CEO of Jindal Power, which is developing Etalin project in Jt Venture with Arunachal Pradesh govt, agreed that project is unviable: “In the current situation, the project doesn’t look like an attractive investment in view of huge investment.”https://t.co/oIz9n3CMd2

— SANDRP (@Indian_Rivers) May 8, 2020

Such economic impracticality is not a one-off incident. The 400 MW Maheshwar Hydro Project in Madhya Pradesh, first cleared in 1994, was terminated this April. The termination order states the cost of power to be abnormally high, above ₹18 per unit. As of last August, in Arunachal Pradesh alone, 103 private hydropower projects failed to take off because private sector companies could not set up operations.

Despite this, a contrary trend is visible. The government is encouraging private and state developers to meet India’s Hydropower potential of 1,45,000 MW. This is evident through major interventions, the latest being the categorisation of Hydropower projects over 25 MW as “renewable energy”, thereby making large hydro projects eligible for financial incentives and cheaper credit. As of 2019, the Central Electricity Authority (CEA) listed 36 new hydropower projects to be commissioned in the coming years — and these are just the “large projects”.

But, is there really a demand for hydropower projects? And why are they becoming unviable?

What’s With the Demand for Hydropower?

Hydropower is often seen as one of the ways to meet the increasing demands of power in the country. But what if this justification is based upon an inaccurately projected figure of demand?

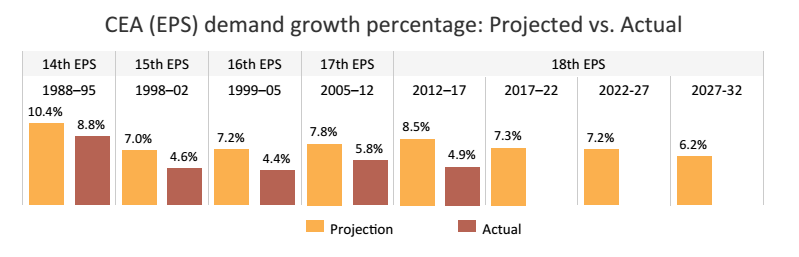

For decades, the CEA’s power projections are infamous for overestimating demand. While the demand growth has been moderate in recent years, “the variation between projected demand and actual demand is significant,” states the Price of Plenty report by Prayas Energy Group.

These over-estimations are one of the reasons that India is in a power surplus situation. Even for 2019-20, the CEA had projected a surplus of 5.8% and a peak surplus of 8.4%.

If this is the case, then what is the need for new hydropower projects? South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers and People (SANDRP) conducted an analysis on the performance of India’s existing dams. Upon comparing the power generation figures over 29 years, SANDRP found that 89% of hydro projects have been under-performing in terms of the power they should be generating.

Despite an over-estimated demand projection and underperforming dams, the push for expensive large hydro projects continues. But why have the proponents of these projects been unable to break-even in the hydropower business?

Untenable Plans, Unviable Business

Apart from the high capital expenditure initially, the delays caused during the construction of hydro projects also lead to cost overruns. The reasons for these were analysed and illustrated in a report by PwC in 2017; one of these are delays owing to improper public consultations.

Many times, “public consultations” —an integral section of the prescribed processes of Environmental Clearances under the EIA by the MoEFCC — are not followed. Public agitation is soon to follow after which local communities often drag the project proponent to court. Note that by this point, major capital expenditure has already been incurred by the said company.

This was the case in the fight against the 243 MW Kashang Project in ecologically fragile Kinnaur, Himachal Pradesh. Stage 1 is currently operational in this four-stage hydro project. For the last decade, the locals fighting a case in the Himachal High Court and the National Green Tribunal challenged how forest and environmental clearances could be given to the Project without the Gram Sabha’s No-Objection Certificate. The loss of their endemic chilgoza pine forests was one major cause of opposition.

A Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) performance audit of the Kashang Project from 2018 found that even after spending ₹1,169.75 crore up to March 2017, the project was still incomplete. The initial cost proposed was ₹708.16 crore, and the project was supposed to be completed by 2015.

Closely related to the costs overrun is the ecology of the area designated for hydro projects. Since many hydropower projects are being proposed and constructed in the Himalayan regions, access to these areas is an additional cost. But, companies experience major set-backs when they face “geological surprises” in the form of a geological obstruction to the construction work. Take landslides due to poor geology, unusually high geothermal heat, for instance.

“If time and money is spent on proper environmental Impact assessments, such accidents would not be a surprise at all,” says Shripad.

Shripad makes a good point. A report by Himdhara Environmental Group shows that in Himachal Pradesh, where 153 hydropower projects have been commissioned, 67 hydropower stations are vulnerable to landslides. 97% of the state is prone to landslides; yet, hydropower projects continue to be proposed in full throttle.

These ‘geological surprises’ have huge costs. The same CAG report illustrates this in the context of the Kashang Hydro Project, stating that “a survey carried out in November 2013 further showed that the area was covered with a thick layer of overburden/glacial fluvial deposit, and was not fit for construction of the buildings.” That the ecological and economic costs are closely connected is stated by the report when it says, “had this been done earlier, it could have avoided an expenditure of ₹2.80 crores…”

As of 2020, such delays in hydropower projects had resulted in cost overruns of approximately ₹53,739 crores, with some of the dam projects extending to as much as 148% of its initial costs.

This begs the question: if the government is well aware of these cost overruns and non-viability, why are they still promoting this sector for power generation?

Flowing Ahead

“We are also unable to understand if there is a need to continue with hydropower,” shares Shripad. “One reason [for continuing it] is that in Himalayan states where such projects are coming up, there are only limited ways that the government can show that they are putting money into large investments.”

Hydropower is also being pushed in the name of “clean” and “green” energy. But, environmentalists have countered that they are anything but that.

Even if we consider the increasing demand for power in India, hydropower may still not be viable because of their cost overruns and underperformance. Instead, solar provides a better alternative.

Also Read: Why Aren’t We Making Hay as the Sun Shines? Moving to Solar Rooftops

Solar projects can be installed at low or high capacities, as per demand. Consequently, they are easier to finance and plan for, besides being more flexible to balance demand and supply. Moreover, solar projects take less time to become operational, as opposed to the many years (read: decades) that hydro projects can take. Having said that, the environmental costs of solar — the vast land acquisition, the disposal of batteries, etc. — also need to be accounted for, while considering this shift.

Featured image of the Tungabhadra Dam courtesy Bishnu Sarangi/Pixabay

[…] Also Read: The Risky Business of Large Hydropower Dams […]

[…] impacts, especially when it comes to large infrastructure. In Himachal Pradesh, for instance, 97% of the state is estimated to be under serious threat of landslide hazard risks, and yet, more dams […]

[…] impacts, especially when it comes to large infrastructure. In Himachal Pradesh, for instance, 97% of the state is estimated to be under serious threat of landslide hazard risks, and yet, more dams […]

[…] The risky business of large hydropower dams […]