Written by Ishani Pant

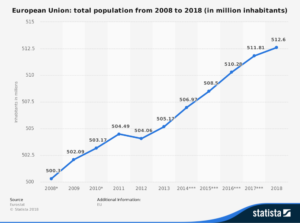

Mutagenesis is the process by which the genetic makeup of an organism is altered either due to natural circumstances or laboratory procedures. This year, on July 25th, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) delivered a judgement stating that organisms created through mutagenesis and other new gene-editing techniques would be subject to existing EU GMO regulations.

“Releasing these new GMOs into the environment without proper safety measures is illegal and irresponsible”, emphasised Greenpeace EU food policy director Franziska Achterberg, “particularly given that gene editing can lead to unintended side effects. The European Commission and European governments must now ensure that all new GMOs are fully tested and labelled and that any field trials are brought under GMO rules.”

In other words, GMOs will continue to be strictly regulated within EU boundaries. This has sparked dissent among those who consider the verdict a step backwards for the agricultural sector. But the verdict has also garnered plaudits from those who believe the decision will encourage safe food production.

The issue, however, has been reduced to a debate between these two opposing factions that prioritise their agenda over the others’ interests. While this is a part of the problem, this back and forth can be better comprehended as a web of differing understandings and misunderstandings harboured by each faction with regards to their own ideas and those of opposing parties. The matter is further complicated by the lack of substantive scientific data on the different aspects of the impact of GMOs.

A Persuasive Pitch

For a preliminary understanding of the issue, let us consider the GMO v/s pesticide debate. Many believe that GMOs provide the ultimate solution to rid agriculture of the harmful chemicals that make up industrially produced pesticides. They assert that the ECJ judgement has compromised any efforts to end the increased usage of pesticides, thus denying Europe “greener crops”. Moreover, they posit that the restrictions will drive out GMO research projects from Europe to the United States.

There exists evidence to support these claims. For example, an American company called Calyxt used genome-editing techniques to manufacture a wheat that required less fungicide because it was resistant to powdery mildew. While the U.S. government has not initiated any special regulations, the EU has declared that for Calyxt’s wheat to be approved for sale, the company must present the government with more research to substantiate their product’s alleged benefits.

This would require additional time, funding, and resources. The result is that American consumers have access to this variety, while EU citizens do not. This situation is clearly not in tandem with the desired development of European agriculture.

The Cogent Opposition

Why then is the EU continuing to impose restrictions on GMOs? There is no singular answer, and the supporters of the ECJ ruling have made many compelling arguments.

One argument is that the increased use of GMOs is not proportional to the decrease in the use of pesticides. Examples have been recorded of reduced as well as increased use of pesticides after the introduction of GMOs. Thus, science cannot conclusively determine how the introduction of GMOs affects pesticide usage, much less whether it can completely eradicate the consumption of such harmful chemicals.

Further, GM crops are designed to be resilient towards pests and diseases. As a consequence, they release their own form of pesticides. These self-produced chemicals, while effective, leave residues that have not yet been proven as entirely non-harmful to humans. Hence, the extent to which GM crop normalisation will reduce the chemical levels in our food is uncertain.

The bottom line of this argument is that pesticide use is already regulated by EU governments; in addition, the EPA and WHO continually facilitate research in search of alternatives to pesticides. Therefore, deregulating GMOs for the purpose of reducing pesticide use is unjustified.

Besides, the available evidence on the health risks of GMOs has been found through either theoretical studies or experimentation. Therefore, the circumstantial side effects of these products cannot be determined as yet, making the normalisation of GMOs a dangerous bet.

This argument concludes that introducing GMOs to the market with fewer regulations may lead to unpredictable results, which is a risk that outweighs any alleged benefits

GMOs and the EU

The EU has always upheld a precautionary principle with respect to GMO food/feed production. Policy-makers have prioritized human economic interests, animal health, as well as environmental concerns when deciding regulations. The European Food and Safety Authority (EFSA) is an agency under the European Union which generates independent scientific reports and assesses the risks involved with each food product. This ensures the EU is equipped with the data required to substantiate decisions and decide regulations.

These particular regulations on the cultivation of GMOs, unlike the laws on marketing and importation, are decided individually by the governments of EU members. They may allow or prohibit the growth of GMOs depending on factors such as land availability, socio-economic priorities, and human health. Hence, the outlook towards GMOs within the EU is neither unanimous nor temporally consistent.

In order to assess the response to the regulation of GMOs, the European Commission had requested a comprehensive report based on questionnaires, interviews, and surveys administered to stakeholders and concerned authorities. It was found that 50% of the respondents believed the EU GMO legislation was not in tandem with their vision for growth in agricultural biotechnology because it ignored the proven benefits of GMOs with the blanket privileging of environmental protection and human health. The study also brought to light that public acceptance of GMOs cannot be easily documented because GM-labeled products are not widespread in EU markets; however, a generally negative public attitude was noted.

The report suggested that there should be a greater awareness of the scientific facts vis-a-vis the risks of GMOs amongst the general public, along with an understanding of the authorization procedures that precede governments giving GM products a thumbs up. Only then can an informed opinion be more confidently put forth.

Finding the Sweet Spot

While GMOs come with several tangible and some theoretical benefits for the agricultural sector in Europe, other concerns cannot be ignored. It is true that higher quality research, better crop varieties, higher yields, and lower prices are all potential advantages of greater GMO usage.

Having said that, there is a potential for producers of such crops to genetically modify them so as to make the yield infertile. This way, farmers are forced into buying new seeds to sow after every harvest. By making non-GMO crops extinct, the agriculture sector could irreversibly become dependent on GMO-seed producers. The result would be a hazardous oligarchy of corporations controlling the world food supply. Hence, the risks of relaxing regulations can pave way for dangerous repercussions on public health and our environment.

All in all, given the ambiguity and contradictions in GMO research, the most justifiable stand on the issue is the middle path. GMOs and pesticides cannot be judged in a binary against one another. Bearing in mind that pesticides are harmful in large quantities, GMOs are not the faultless solution. The ECJ ruling may have caused stagnation in the GMO market, but it still cannot be dismissed as regressive or unjustified.