Co-authored by Sunalika Singh and Charith Reddy

As the third largest consumer of energy in the world, India is far from energy independence; with the country importing $125 billion of crude oil, a rise of about 40% from 2017-18, it’s time to search for answers in other domestic resources. Shale oil and gas have been touted as a potential solution.

Recent amendments made by the Indian Government regarding the extraction and utilization of shale as a major energy source have opened avenues for a potential reduction in the dependence on coal and crude oil. However, this comes with significant costs that the subcontinent may not be ready to deal with.

An Economic Gold Mine

The US’s tryst with shale is largely hailed as an economic success; energy prices have dropped, thus making it a lot more affordable.

Estimates suggest that in the period between 2007 and 2013, gas bills fell by more than $10 billion annually. Further, In addition to an increase in all-round economic activity, incomes have increased and more people have jobs; National Geographic projects that the shale revolution can potentially add over $113 billion to federal and state revenues by the year 2020.

Economically, it seems to be a gift that keeps on giving.

An Environmental Hazard

One can say that the economic benefits of shale do not outweigh the environmental costs.

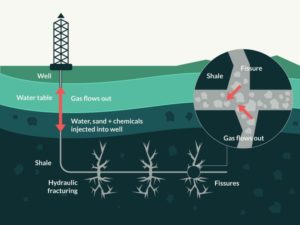

At the most fundamental level, the method of extraction for shale oil and gas is itself contentious. Known as fracking, it may be defined as the technique of drilling, vertical or horizontal, into the earth after which a highly pressurized mixture of water, sand and a thickening agent is injected into shale rock in order to fracture the formation and release the gas inside. The gas is then directed out to the head of a well, from where it is extracted.

As a result of this, numerous fissures are created deep below the surface which act as channels for gases, chemicals and potentially radioactive substances. The underground water, now infused with chemicals such as methane, iron and manganese among others, is polluted and possibly carcinogenic. This can easily seep into and contaminate wells and aquifers. This is a serious health concern, as exposure to such toxic water can result in severe neurological, gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, urinary and respiratory disorders.

Fracking also requires a lot more water than that used in drilling a conventional well, to the extent that is almost wasteful. Statistics suggest that in the US, approximately 70-140 billion gallons of water are required to fracture over 35,000 wells annually. This exact amount could alternatively have been employed in fulfilling the annual water needs of 40-80 cities with a population of around 50,000. Further, the amount of water consumed for these operations increases year after year. Mr Shashikant Yadav, an Energy Law Research Scholar with TERI, suggests that the consumption of water to produce the same amount of shale oil increases by 400% every five years.

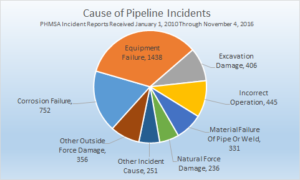

Accidents are also fairly common with shale projects. The North Dakota pipeline accident of 2017 is a grave example of the same, wherein a broken pipeline caused a spillage of over 2.9m gallons. What’s scary about these accidents is that a majority could have been avoided, pointing to the need for a rather specialized oversight and workforce.

So where does India stand on this spectrum?

The Indian Narrative

While we are in desperate need of the benefits of shale, the costs that we will have to bear are amplified — because of our thus-far careless attitude to our resources and ineffective legislation.

In 2018, the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas (MoPNG) amended the Petroleum and Natural Gas Rules (1959) to include shale in the definition of petroleum. Subsequently, researchers and operators under exploration contracts, or leased license holders got the green light from the administration to begin explorations for unconventional hydrocarbons.

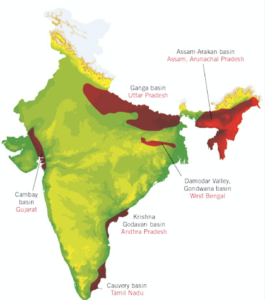

It has been speculated that Indian shale gas reserves are greater than the remaining traditional gas resources. The reserves are estimated to be around 100-200 tcf (trillion cubic ft.) located in six sedimentary basins; Cambay, Krishna-Godavari, Kaveri, Assam-Araken, and the Indo-Gangetic plain.

However, the environmental costs, especially the water costs, of such initiatives are something that India must carefully assess before moving ahead.

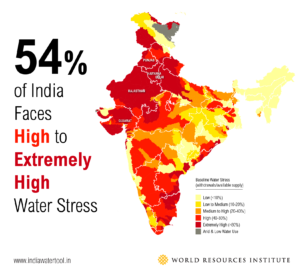

Exemplifying serious ‘water-stress’, the Composite Water Management Index report published by NITI-Aayog says that India is currently facing its worst water crisis ever. Our groundwater resources are being depleted at a dangerously rapid rate; it is estimated that at the current pace and without viable water management techniques, the national demand will far exceed the supply of freshwater by 2030. Introducing fracking into this already dire situation is, therefore, problematic. Where will the government fulfil this ever-increasing demand for water from?

Water-stressed regions within the country, or regions where supply is unsustainable, are bound to suffer the most, especially if they are near the marked areas for exploration. The water used in shale oil and gas extraction will mean the loss of water use elsewhere; likely be diverted from the limited supply for irrigation practices, crop production, hydro-power generation, and other basic demands, creating day-to-day economic obstacles for households.

Add to this the fact that the rural poor will be the most affected due to the pollution produced; it has been found that the concentration of methane in household water supplies in the vicinity of fracturing sites is about 17 times higher as compared to wells for conventional oil/gas, all of which can lead to significant cardiovascular, respiratory and neurological diseases.

While the unavailability of water and the significant pollution risk is one face of the issue, the other has to do with a rather undefined set of policies to govern such projects.

Confused Policies

India has drawn serious criticism for its weak, rather unenthusiastic implementation and reinforcement of environmental laws and regulations. Citizens of India do not have the right to mineral resources underground the land they own. While the respective states have constitutional rights over water, ‘hydrocarbons’ as resources are governed by the Center. In 2013, there was a Supreme Court judgement stating that people may have mineral rights; however, no real follow-ups have been conducted to clarify the matter. Further, an Indian law or environmental regulatory is yet to specifically define the term ‘aquifer.’

With fracking in particular, 50 blocks have already been given out with no proper pilot project in place. Although a draft Policy for the Exploration of Shale Oil and Gas in India was released in 2012, the guidelines for Environmental Management during Shale Gas/Oil Exploration and Production are riddled with loopholes. They do not comprehensively address any water-specific concern or provide any regulatory blueprint for decisive action and operation.

Mr Yadav proposes that a large part of the problem will be solved if policymakers recognize this difference and separate the legislative frameworks and environmental clearances for conventional hydrocarbons from the unconventional. He remarks, “this would be like opening up an entirely new sector dedicated to unconventional sources like Shale. Employment will be created, universities and research institutes will be set up.” To get these projects up and running, it is absolutely necessary to create a resolute legislative backbone, which is something that India seems to be missing at the moment.

High Hopes

In an effort to increase domestic production and move towards self-sufficiency, this landmark policy is expected to serve as both an enabler of and encouragement for future investment in energy exploration and production. While there is a desperate need to move away from traditional resources and reduce our oil import bill, it’s even more important to not rush this move.

The process must begin with smaller steps to judge the feasibility of the program. Shale should remain a heavily-supervised pilot project, till policies are ironed out and contingencies are taken care of. We must be well-informed of consequences and proceed with the utmost caution; reckless action will get us nowhere and leave us with empty pockets.

Featured image courtesy Nandu Chitnis|CC BY 2.0