“Elections”. It is a phenomenon that evokes manifold emotions in the Indian mind. One may romantically perceive the process to embody the celebration of a vibrant and functioning democracy; others, as a philosophical periodic renewal of the social contract; many may associate futility with the shenanigans associated with them. Be it an optimistic or concerned point of view, it is undeniable that elections play a central role in Indian democracy.

What adds vibrance to any election is the richness of the politics around it, and the varied public discourse and public participation it elicits. Yet, not all elections are the same in a democracy, and there is a difference in the ways in which citizens approach elections at different levels. Albeit unsurprising to a certain extent, the degree of imbalance in terms of voter engagement across different electoral levels, especially in today’s urban settings, is a serious cause for concern and introspection amongst Indian citizens and political parties.

Local elections affect us more than we like to believe

The next time you find yourself in a conversation about “good governance” in India, ask yourself if there is a mismatch between the level at which the service is being delivered, and the level of electoral politics. Central legislation or internal security may unite voters at a national level, and rightly so. However, the fact remains that several aspects of governance — such as sanitation, waste management, road maintenance, local transportation facilities, street lights, and so on — which affect urban voters’ daily standards of living are not handled by Modi-Shah or the Union Cabinet, but rather by the third tier of democracy, embodied by your local urban corporator.

The 73rd and the 74th Amendments to the Constitution brought about the Panchayat Raj system in the early 1990s, giving agency to local representatives, who are accountable for solving local problems. Although the level of devolution varies across states and cities, in urban areas, corporators have the agency and opportunity to attend to, if not solve, the most immediate and proximate woes of a citizen.

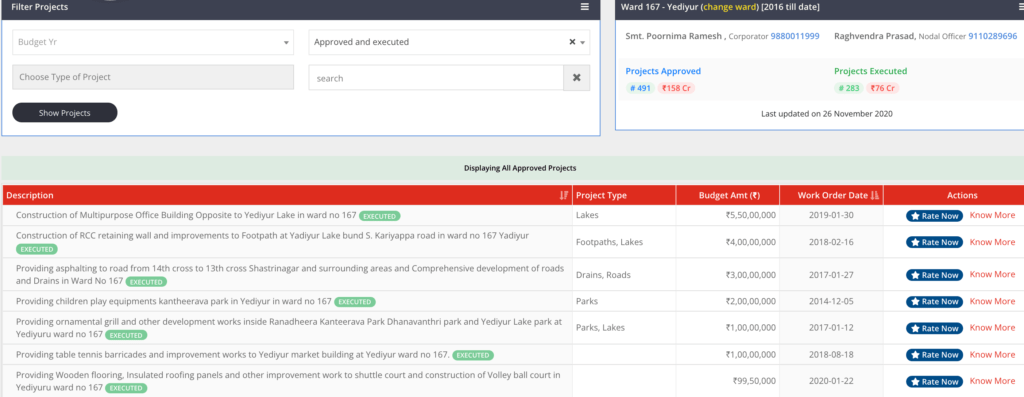

Yet, this remains to be one of the most ignored aspects of Indian democracy, with local politics (and its relevant elections) playing subordinate to state and national politics. While citizens may be aware of their local MP or MLA, there is generalizable anonymity around the identity of their corporator, or the elected representative meant to keep their streets clean, roads tarred and street lights on. Such invisibility is especially hard to accept, especially in India’s metropolitans where thousands of crores are spent by the municipality every year. For instance, irrespective of the ward in Bengaluru from the list, around ₹100 crores will be spent in that ward in one term. In total, Bengaluru’s municipal corporation, the BBMP, budgeted ₹9,287 crores to be spent in 2021.

Despite these high budgets, the invisibility around municipal governance remains, translating thereafter into abysmally lower turnouts at local urban elections. For example, the average voter turnout in the 2015 BBMP elections in Bengaluru stood at just 44 percent, at least 10 percentage points lower than the turnout for the General elections conducted just a year earlier, irrespective of the constituency. A 2020 report by CVoter and Polstrat studied the reasons behind low voter turnouts at municipal elections in Bengaluru to find that the most common reason cited by citizens was the lack of awareness regarding the 2015 polls, with women especially claiming to have just not heard about the BBMP elections in the first place. A lack of trust in existing political parties and a paucity of good candidates were other restraining factors highlighted by the report.

Why municipal elections are seen differently

One major reason that alienates voters from local politics is the unpredictability at this level of political representation. Elections are not conducted regularly, corporations continue to be suspended, and state governments regularly dictate changes in the organisational machinery.

Take the case of Chennai Municipal Corporation, the oldest municipal body of the Commonwealth of Nations outside Great Britain, which has remained suspended since 2016 because elections haven’t taken place. This could possibly be credited to the difference in the autonomy of the Central Election Commission, which conducts elections to State and Central legislature, and the various State Election Commissions, whose primary responsibility is to conduct elections at the Urban Local or Panchayat level.

Whatever the reason may be, such inconsistency and unpredictability seriously impact the legitimacy of local electoral representation, not only in the minds of voters but also the representatives. It dilutes the vigour around these elections, resulting in poorly incentivized candidates, which then affects the delivery of services at this level of governance.

Local Politics: An Unviable Political Career

The passive language around conducting municipal elections not only damages how voters perceive them, but also interested candidates. The instability experienced by local political representatives leads to their subordination to prevalent state politics. So, for municipal democracy to flourish, municipal politics must be a fulfilling and rewarding career option in itself, instead of it being a stepping stone to larger roles within state or national-level politics. This inherently disadvantages independent community leaders with a strong local understanding, who do not have ambitions to fight the Lok Sabha or State Legislature elections from being given a ticket to contest.

Municipal governance is a challenge in itself, with its own nuances, requiring people with narrow specialisation and keen interest to take them up. The subordination of municipal politics does a disservice to citizens and the larger ethos of a public-spirited democracy.

Introducing a Hyper-Local Party

To tackle local urban challenges head-on, and to prioritise the non-glamorous aspects of public service, one proposed solution could be that of a hyper-local political party. What does this mean? It would be a political entity that spends all of its energy, time, and resources addressing local concerns and solving local issues, without the ambition of upscaling its political ambitions. Such a political party would only fight municipal elections of one particular city, and not those of centre and state legislatures. The idea behind this kind of political organisation would be to provide a dedicated space for individuals who wish to commit their time exclusively towards tackling local challenges faced by the electorate. It would be an opportunity for leaders to represent their community without having to subordinate their local interests over state or national.

This idea would possibly invite major scepticism and criticism from various sections of voters and political actors, but even such engagement would amount to an increased discussion and engagement with local concerns of the citizen, creating a net positive spillover for municipal governance. Bengaluru NavaNirmana Party (BNP) is currently the first and only political party of its kind, with a singular focus on just one city’s local governance. In the past two years of its existence, while it has managed to build civic credibility through its work, and a volunteer base of over ten thousand people, its electoral abilities are yet to be put to test.

Most political experts would not give the BNP any chances of displacing the mainstream national parties, but the opportunity to find out is just around the corner. Elections to Bengaluru’s Municipal Corporation, the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike is expected to be held in 2022. India’s fourth-largest municipal corporation has been run by government-appointed officials since the last council’s term ended on 10 September 2020, with no polls taking place since.

What’s in it for a voter?

With a hyper-local party, voters would get dedicated workers, who see solving local problems and contesting municipal elections as an end in itself, and not only as a means to achieving their political party’s larger ambitions at the state or central level. This shift towards perceiving local politics as a meaningful opportunity to represent, govern, and offer solutions to citizens can rejuvenate India’s municipalities.

It is also well established that voters’ priorities and expectations may differ depending on the level of governance in question. Odisha in 2019, wherein the electorate voted in two different political parties (the BJD and BJP) at the state and the central legislatures, or Delhi in 2019-2020 (between AAP and BJP) are recent cases in point. This tendency of the electorate is encouraging for local parties and representatives who dedicate themselves to contesting municipal elections.

The Youth Appeal

One of the most exciting aspects of local politics is the ability to absorb youth into it. Unlike the Lok Sabha or the state legislature, candidates need not be 25 years old to contest an election at the municipal level, with the bar being set at just 21 years of age. Moreover, the size of wards is significantly smaller than the Lok Sabha and state legislature Constituencies, making it more feasible for young individuals to put up and manage a political campaign. For example, the Bengaluru South Lok Sabha Constituency has 8 State Legislative Assembly constituencies and 90 BBMP wards. This decentralised and localised structure of municipal wards could be a great canvas for young individuals to create a meaningful and visible impact on the lives of the people. Local elections are a great way to channelise the youth’s energy towards creating a meaningful impact in their immediate societies.

This domain is not without precedence, with many young politicians having charted their own success via council elections. Arya Rajendran who currently serves as the mayor of the Thiruvananthapuram Corporation is just 22 years old, the same age at which Devendra Fadnavis became a councillor, who later went on to become the Mayor of Nagpur and then the Chief Minister of Maharashtra. As a sign of further encouragement in this aspect, almost 50 per cent of the candidates for the recently conducted municipal elections in Chandigarh were below the age of 40.

Picking the Low-Hanging Fruit

Political representation can concern itself with legislation around national security, industry, trade, livelihoods, and employment, among various other aspects. But what one must not forget is that political representation must also concern itself with clean streets, proper waste management practices, effective sanitation, quality local transport, and several local aspects which directly impact citizens’ everyday lives. Municipal elections and local politics are much more significant than the importance it is given by voters, political parties, and state election commissions. A spectacle and celebration in itself, they deserve a special cadre of young and committed politicians from across parties and ideologies to contest, who see local governance as an end in itself and not as a means to fulfilling their higher political ambitions. Uniform, predictable, and efficiently managed municipal elections will go a long way in evoking positive perceptions around local governance in every Indian voter’s mind.

Featured image of BNP members attending a ward committee meeting with officials to get local issues resolved. So far, the party has a presence in around 130 out of 198 wards in Bengaluru, while teams are still being formed in the others.