Written by Ahan Bezbaroa

With rousing revelations, such as the IPCC’s recent Special Report that identified 1.5 degrees Celsius as the limit to which the rising average global temperature must be contained by 2100, it seems as though environmental conservation is finally being recognized as an important concern in policymaking. Responding to pressures exerted by an increasingly impassioned and active civil society, governments across the world are slowly and clumsily, tottering towards a truer sustainable development.

Undoubtedly, the claim made above is overarching and incognizant of the complexities of the actual situation. Even then, well thought out and progressive policy approaches are emerging — like the Solid Waste Management (SWM) Rules of 2016, the Climate Resilient Zero-Budget Natural Farming initiative by the Govt. of Andhra Pradesh — have their shortcomings; poor implementation will impede even the most benign of ambitions.

Implementation is Key

Due to the massive size and population density of Indian States, it becomes a mammoth task for a single agency, such as a state government, to ensure compliance by all urban and rural settlements to a set of policies. Consequently, the importance of civilian responsibility becomes more pronounced. It is to redress this difficulty that in 1992, the 73rd and 74th Amendments to the Constitution –the Panchayati Raj and Nagarpalika Acts respectively- were enacted.

These landmark legislations were a serious attempt at devolving of State power to smaller units of government, namely the Panchayats and urban local bodies. The three-tier Panchayati Raj system has been instituted pretty uniformly across the country; Gram Sabhas, Gram Panchayats and Zilla Panchayats have been created and are effective units of local governance.

The urban parallel to the smallest unit of the Panchayat governance system (the Gram Panchayat) is the Ward Committee (WC). If implemented competently, the act would allow the urban citizenry to directly engage with governance by providing a space in which they could raise concerns, as well as to oppose initiatives that would be detrimental to the constituency — the creation of a landfill or a power plant or even a flyover!

The Case of Bangalore: Wards and Waste

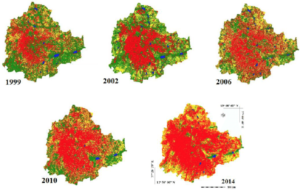

In the last few years, Bangalore has made several efforts towards making WCs functional. Concerned citizens and NGOs mobilized against, and filed petitions in court to arrest rapid environmental deterioration. In the last several decades, rapid, unplanned development has led to foaming, toxic lakes, loss of tree cover — from 68% in 1973 to 25% in 2012 — and toxic landfills that have poisoned entire villages.

Common to all these issues is that administrators and those in power took decisions without consulting local residents. Lacking a local governing body to represent them, citizens took recourse to physical mobilization and moving of the judiciary. While these are valid and effective methods of contesting governmental decisions, it is certain that an effective WC would be a less disruptive as well as more constitutional and democratic, method of dissenting with an administrative operation. Considering that the 73rd and 74th amendments to the Constitution were brought in almost 30 years ago, the failure to have adequately implemented them speaks, to a certain extent, to the ineffectiveness of our democracy.

From this, let us consider the SWM Rules, 2016. It is an example of fairly progressive and comprehensive legislation that for instance — in a rare display of backbone — directs the powerful industrial bloc to adopt Extended Producer Responsibility by ensuring that a system exists for the collection and processing of the waste their products generate. Other directions within the document, such as, the identification of waste generators as the parties responsible for ensuring proper (segregated and appropriately collected) disposal of waste, the acceptance that landfills need to be regulated better and the directive to institutionalize waste-to-energy initiatives, are all heartening, commendable developments in the positions adopted by policymakers that reflect a change in their very understanding of waste.

These rules also direct the creation of a Central Monitoring Committee to monitor implementation. At the state level, the rules mandate that State Pollution Control Boards and district level authorities(Magistrates, Deputy Commissioners or District Collectors) carry out regular status reviews. The Central Monitoring Committee is chaired by the Secretary of the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MOEF&CC) and is comprised of stakeholders from central and state governments as well as urban local bodies and census towns. The multilevel review system and the inclusion of varied stakeholders is refreshingly inclusive. And yet the question remains, is all this enough to ensure effective implementation?

To answer this, one needs only to look at the ground reality; litter still lines our streets, mounds of gathered garbage are ubiquitous in our cities, and our landfills continue to grow. In most of the country, any effort to segregate the garbage produced in one’s home is entirely undone by garbage collection in a single truck; without divisions for different categories of garbage, and eventual dumping in a single dump site.

Since last 2-3 hours, KCDC (BBMP) is releasing highly toxic stench from its Kudlu plant. Residents of Kudlu, Hosapallya, Somsunderpallya, HSR & Parangipallya are severely affected by the poisonous gases, & they need immediate help @BBMPCOMM @CMofKarnataka @KHHSPRWA @DeccanHerald

— Dr Ravindra, Ph.D, FRSC (@Dr_RVS) December 17, 2018

If, for instance, WCs were uniformly empowered and given the responsibility of organizing the collection of solid waste from each ward as per the SWM 2016 (article 15), the efficacy of waste management systems would improve drastically. Citizens could hold committee members directly accountable for failing to require garbage collectors to collect different categories of waste separately and disposing of it adequately. The rules themselves direct State Pollution Control Boards (SPCB’s) to “enforce these rules in their state through local bodies”.

Unfortunately, so far it has been city councils and corporations that have acted as the local bodies being coordinated with. In Bangalore, it has been the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagar Palike (BBMP) that has been exclusively in control of solid waste management in the city. BBMP’s solution was to contract out garbage disposal to private organisations with disastrous consequences.

In the cases argued before the Karnataka High Court, challenging such violations of peoples’ right to life, where their ancestral areas of residence were turned into toxic hells, a division of the Court agreed that waste must be managed at a ward level (case W.P. 46523/2012). The rationale behind this decision was communicated to the MOEF&CC while the case was being decided and eventually incorporated in the SWM, 2016.

It’s Time to Begin

Although it took more than a year since the High Court order was delivered, it has only just begun to be implemented. On the 27th of November 2018, the BBMP issued a directive to all WCs to mandatorily hold public meetings in the first week of each month to build citizens engagement. Such a move makes members of WCs more accountable to the residents of their wards and hopefully, will eventually lead to effective waste management, and an overall improvement in governance. While it has only been a little over two months since this directive was issued and it will take a lot longer for tangible change to be discernible, it is, hearteningly, a step in the right direction.

If citizens across the country learn from this example and organize into an alert and motivated civil society, the true power of local governance can be harnessed. If every city is able to institutionalize local governance, the principle of democracy that motivated the 73rd and 74th amendments will begin to be realized. If every locality is thereby enabled to hold their local governing bodies accountable, it will become immeasurably more difficult to carry out the wanton mismanagement, not just of waste, but of everyday governance.

Featured image courtesy Mike Prince|CC BY 2.0