Written & Photographed by Ipsita Mishra

Libraries have always overwhelmed us with the extensive information preserved in the form of books, and have been a reader’s paradise taking her to a different world of imagination and knowledge.

Delhi has always been a vibrant hub of education and literacy, and one of the most important aspects of its literary culture is its libraries. However, the current state of libraries in the city is deeply troubling. These learning institutions, once the delight of researchers, academics and general readers, are losing their importance in an almost entirely digital world.

A Tragic Tale

“We have not bought a single book from last ten years. We don’t receive any funds and last year the library did not have electricity for ten days due to non payment of bills”, said an official on the condition of Hardayal Municipal Public Library. This is the oldest library in Delhi, having been set up close to 150 years ago, and is struggling to survive. It lacks basic amenities like Air Conditioning, water supply, clean toilets, chairs and the basic prerequisite for any library — books.

A lack of funds, resources and staff in libraries like the Hardayal Library have proved to be the biggest reasons for these knowledge banks to turn into mere buildings. The local libraries are usually funded by civic bodies, which in turn get funds from the Delhi Government. Actually receiving these funds is usually the biggest challenge.

In countries like the United States, public library systems receive a fair share of attention — $35.96 per capita is spent annually on them. The same figure for India is around 7 paise.

Further, there is no real source that covers the state of these libraries; these could be anything from a room with a few books to larger privately funded libraries.

The 3rd edition of India Public Libraries Conference, hosted by the Nasscom Foundation and held in Delhi, brought to light the apathetic attitude towards public libraries in the country and highlighted the need to tap their potential. “The main objective was to bring all key stakeholders in the public library space on one platform to deliberate how these libraries can best reach the unreached,” says Shrikant Sinha, CEO of the Nasscom Foundation.

However, while the overall structure of public libraries seems weak, there are a few examples that shed light on how to move in the right direction.

Standing Tall: Delhi Public Library

While libraries are trying to stay relevant in today’s world, the management strategies of some public libraries are an assertion of their efficacy and enduring charm. The Delhi Public Library (DPL) is one such institution.

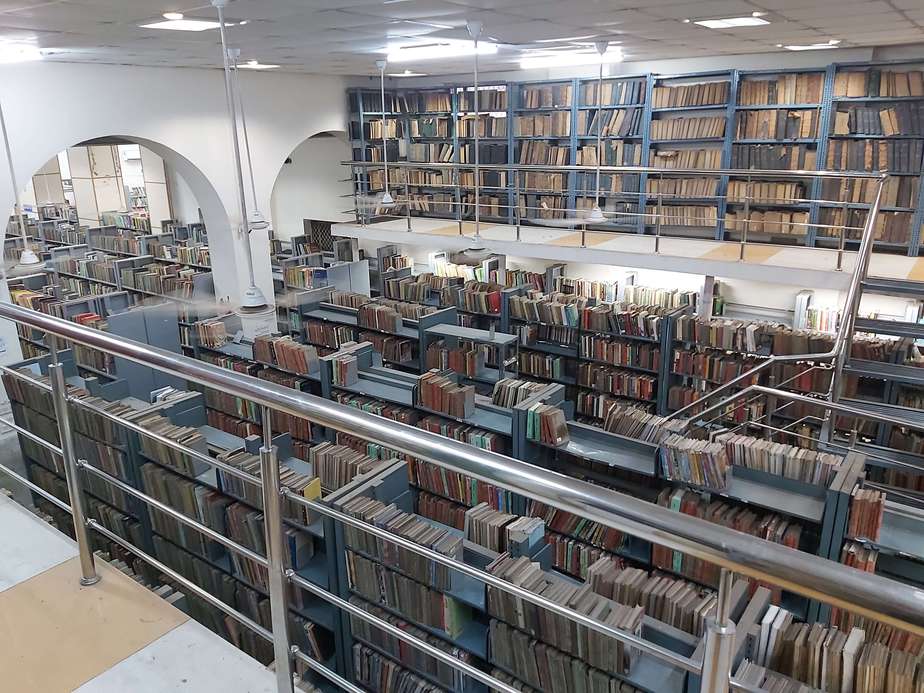

The DPL, which started as the first UNESCO pilot project in India in 1951, is one of Asia’s biggest public libraries with 37 branches in Delhi. It provides library services to 1.58 lakh members of all age groups with a collection of 17 lakh books in English, Hindi, Punjabi and Urdu.

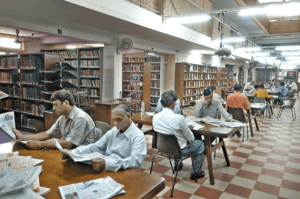

Located at Delhi’s Chandni Chowk, the main branch is a treasure trove for readers. Besides the quiet environment, other factors like ready access to newspaper archives, internet, e-books, and a gym and yoga centre attract many. Shubham, a member of the library who is preparing for NEET, said, “I like to come to this library because I can’t study at home and like the quiet environment here. They also have many facilities at this library which others don’t have.”

The reach of the library goes beyond its walls; its ‘Ghar Ghar Pustak, Ghar Ghar Dastak’ project aims to provide books to the residents of resettlement colonies, slums and rural areas, through 5 mobile libraries and 11 buses travelling throughout the city.

Recently, the Ministry sanctioned Rs 2.2 crore for modernisation and upgradation of the DPL branches — unlike most public libraries that are usually funded by state governments, this library receives funding from the Union Ministry of Culture. However, the number of books issued per year has come down to 7 lakh from 8.4 lakh in 2015. The reason according to the Library Information Officer (LIO) at the Chandni Chowk branch, Sudha Mukherjee, is the increase in the number of students who come to the library with their own books.

“The library conducts membership drives in colleges and organises events, exhibition, summer camps on a regular basis in an attempt to spread awareness about the importance of reading books and to increase membership,” said Babita Gaur, the senior LIO at the same branch. She further added that there has been a remarkable increase in membership; the library now sees more than 250 visitors per day, which used to be 100-150, three years ago.

The Path Ahead:

Public libraries in Delhi, many of which have been through tough times over the last decade, can find a future for themselves by catering to the youth. For starters, several libraries are sprucing up their reading rooms with better lighting and furniture, increasing seating capacity and are simply attempting to provide more comfort.

The library workforce should also be constantly exposed to new ideas and opportunities to constantly evolve; programs like International Network of Emerging Library Innovators (INELI), an initiative by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation that aims to transform library workers into innovators and leaders, should be readily offered. INELI provides emerging library leaders with opportunities to explore new ideas, to experiment with new services, and to learn from one another with an interactive online platform that includes social forums, skill building modules and face-to-face convenings.

The biggest challenge in this battle to make libraries relevant again is to tackle the age-old perceptions attached to them; old, boring places that are only useful if by some act of god, Google cannot give you an answer. An option worth exploring is to draw inspiration from the bookshop-cafe models; these places serve as great spot for casual entertainment and attract a decent crowd. With an inviting atmosphere, the implementation of a model like this might prove to be successful in attracting the youth.

Stakeholders outside the immediate political circles have also been working towards reviving these institutions. The NASSCOM Foundation has launched the Indian Public Library Movement (IPLM), a multi-stakeholder effort to revitalise and transform public libraries into inclusive knowledge and information centres catering to the needs of communities across India. Even corporates like Whirlpool, Nvidia and more have been actively involved in transforming libraries as part of their CSR projects.

While there are success stories like the DPL, on average, public libraries across the countries are struggling to survive. It’s time to turn over a new page and bring back the lost charm of our libraries. We must save our future generations from the irony of knowing about these revered institutions only through the pages of history books.

nice library older people are also sit there.

nice library with more capacity of seats and older people also sit there.