Co-authored by Aarathi Ganesan and Aditya Vikram

By virtue of her burgeoning population and proactive Right to Education policy, India is home to around 310 million school-going children, which is the largest figure in the world. This primary education is being supplemented by an increasingly expansive private and public higher education sector which provides a wide range of skills and specialisations necessary for national growth. According to government estimates, the country is home to over 700 universities and 35,000 colleges. Even so, don’t let the magnitude of these numbers mislead you.

India’s critical higher education sector, in particular, is plagued by various contingencies. For few, this hiccup is understandable given the country’s population and generally insufficient funding for educating it. Nevertheless, the impact of a debilitated higher education sector on the population’s standards of living, social equity, global competitiveness and economic progress are obvious and tangible.

Lack of physical infrastructure has left 20 million students unable to gain access to the education sector. Most education hubs in India are located in urban or semi-urban areas, thereby adding large transport costs to overhead expenses for students from rural areas. This barrier often coerces migration to urban centres; in most cases, it prevents students from enrolling in educational institutes. Building physical infrastructure, therefore, is the call of the hour. On top of this, quality instructors are few and far between, often because of low pay-scales offered.

Many of these physical hurdles have been answered by distance learning programs which provide discrete students with the opportunity to pursue specific degrees. Still, these programs rely on old pedagogical methods which may not resolve concerns of greater educational penetration across the country.

The 21st century’s answer to concerns surrounding distance learning is Massive Online Open Courses (MOOCs). Popularised by platforms such as Coursera, edX, and Udemy since the early 2010s. Endorsed by premier global institutions like Stanford, Harvard, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), these courses mark an important step towards the democratisation and distribution of education across countries. Given the country’s growing internet usage, they could tangibly aide educational spread en masse, revitalizing India’s human resources and industries.

Demystifying the MOOC

MOOCs are open-access online courses which are available to anyone with a smartphone and internet connectivity for a small fee. It differs from a physical classroom integrated with digital infrastructure like smart boards and computers which are expensive for any institution. Instead, MOOCs take the entire classroom experience online by hosting courses taken by professors and instructors from across universities.

Just like any brick and mortar classroom, MOOCs offer readings, homework sets and instructional videos for the student. Additionally, keeping in mind the benefits of collaborative learning, they usually host user chat rooms to discuss concepts and resolve doubts.

An in absentia classroom encourages self-study, implicitly accounting for different learning capabilities and paces

Indigenous Innovation

Available to anyone with an internet connection, the scalability of online features to students across the country could partially resolve problems of equity and access to education.

India has latched on to the opportunity offered by MOOCs by developing several indigenous platforms in conjunction with universities and faculty across the country. The Indira Gandhi National Open University is the largest player in the market currently, hosting numerous certified courses for nominal fees. This is closely followed by Sikkim Manipal University and Symbiosis Centre for Distance Learning which have also gained considerable ground in the sector thereby boosting distance and executive education.

Other private sector platforms, such as Educomp, Everyone and Intellipaat offer similar services to a wide range of age brackets ranging from young students to corporate professionals in need of skill building. LearnSocial is a niche platform which offers MOOCs whose functionality remains unaffected by poor internet speeds. This extends their services to rural areas where connectivity issues may hinder the course’s efficacy. Decentralised online coaching centres and examination preparation platforms have ensured that facility and faculty are redirecting their attention from urban centres to regular households across the country.

Digital India?

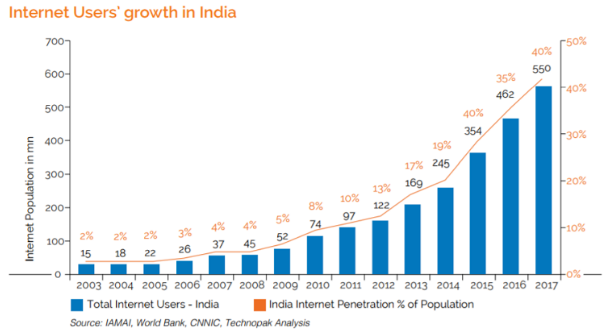

A major concern surrounding the success of such initiatives is India’s relatively low internet penetration, which currently caters to only 35% of the current population. However, recent figures have suggested that this figure will rise to 40% by 2020, accounting for a mammoth 550 million people. India’s market for smartphones has increased substantially due to cheaper models; the recently launched highly subsidised 3G and 4G services have furthered this cause.

Recently, the Central push to shift services to digital platforms have been met with some resistance, but it actually eases the procurement and engagement with technology amongst semi-urban and rural populations. This, in turn, is supported by the Union Budget for FY 2017-18, which allocated specific funds for the development and delivery of MOOCs in tandem with government schemes to improve digital literacy. Therefore, should internet penetration figures rise in the long run, sunny days may be on the forecast for MOOCs in India: their scope, potential and demand would flourish.

Preparing for the Long-term

There lie ample benefits in utilising MOOCs beyond the most obvious expansion of access to education. For starters, recent developments have shown that the government has steadily stepped back from over-regulating institutions within the country by providing them with greater autonomy and dexterity. This also requires less government funding which can be financially supplemented by designing MOOCs to be hosted by aggregator platforms.

For years, universities have been rated and regulated based on their allocated spending on libraries, technology, and infrastructure. Unfortunately, the actual outcomes of these investments are rarely considered. Regulatory patterns have now shifted their focus to the product delivered instead. For all purposes, educational institutions have no choice but to invest in high-quality in-demand MOOCs to balance the focus between quantity and quality. Therefore, online courses have the potential to strengthen national reputation and sustainability of universities.

The Indian MOOC sector has been particularly enterprising, what with the government stepping in with its own platform, SWAYAM, or ‘Study Webs of Active- Learning for Young Aspiring Minds’. More than a clever acronym, SWAYAM hosts hundreds of UGC/AICTE approved MOOCs across varied disciplines in regional languages apart from English. This is a particularly encouraging feature of Indian platforms simply because knowledge retention will improve significantly when taught in the vernacular as opposed to English. With future partnerships alongside Microsoft and edX (founded by Harvard and MIT) to couple with existing collaborations with IIT-Bombay, SWAYAM, along with other indigenous platforms are providing world-class education at student’s fingertips.

Other MOOC initiatives such as the National Programme on Technology Enhanced Learning (NPTEL), which aims to provide technical courses required by industry professionals have also been set up. Approved by national regulatory authorities, such specific content also revitalizes the skill sets of the Indian workforce to make them more competitive. Apart from skill development, they also reduce employee-training costs for corporates and industries, paving the way for better pay scales for their better-skilled hires. A wider range of MOOC subjects can decentralise entrepreneurship from urban centres.

Expanding Access

According to a 2015 higher education report released by Oxford University, there has been a global downturn in the demand for MOOCs. Reasons cited include low completion rates of online courses apart from knowledge retention.

The wide usage of MOOCs could exculpate the government of its responsibility to ensure the development of physical infrastructure, still considered irreplaceable in socially collaborative education pedagogies. At the same time, MOOCs also offer a window of hope for previously marginalized populations who were restricted from participating in the system due to different socioeconomic constraints. Women, the differently abled and senior citizens can all improve their individual destinies beyond what was previously enabled by the state.

While it is true that implementation and efficacy of digital pedagogies are yet to be determined, it is unfair to write off the potential MOOCs possess. After all, the definition of democratized education in India is centred not just around vacuous access, but around its diversities as well.