Competition law has been in the news recently. After over a year-long investigation, the US Justice Department finally filed a much-anticipated lawsuit against Google in October of this year. “Google is a monopolist,” the agency said, “in the general search services, search advertising, and general search text advertising markets. Google aggressively uses its monopoly positions, and the money that flows from them, to continuously foreclose rivals and protect its monopolies.”

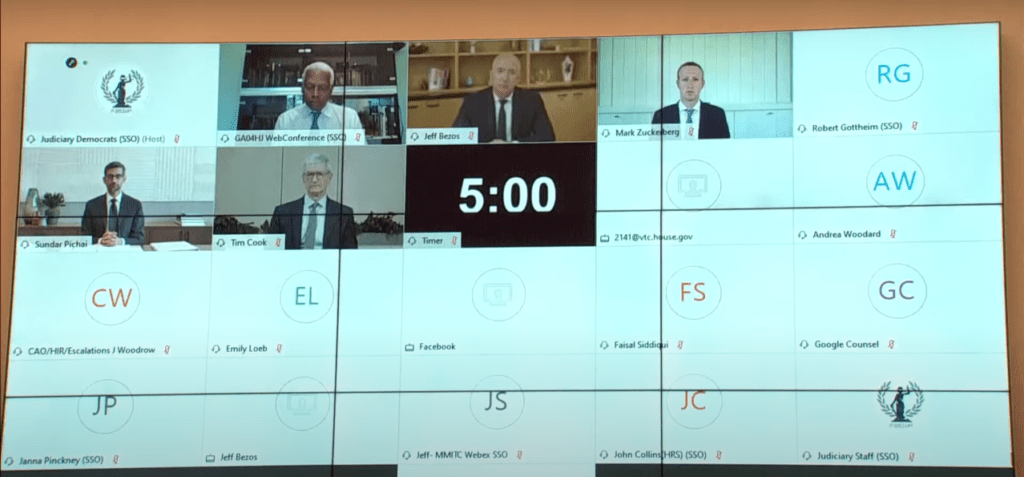

This lawsuit comes on the heels of the US House Judiciary Committee’s antitrust report which recommended significant changes to the operations of four so-called ‘Big Tech’ companies—that is, Amazon, Facebook, Google, and Apple, who are also facing similar allegations.

What is competition law in the first place though? Simply put, competition laws are meant to promote competition between companies in markets by preventing anti-competitive behaviours—which also eventually protects consumer interests.

This is one of the reasons Big Tech companies are being penalised—Google, for example, controls a majority of the search market, and all online shopping services need to be listed on it to stay in business. If Google decides to launch its own shopping service, it could display results for it at the top of the search results, or place its competitor’s results lower down in the search results. This can effectively kill off those competitors—this isn’t just theoretical, after all, when was the last time any of us clicked even the third page of search results when browsing online? This reduces the amount of choice we consumers have, as we might not actually see the best deals for the product we were looking to buy.

Now, what exactly counts as anti-competitive behaviour depends on the specifics of the laws in different jurisdictions, but similar collusive practices, harms linked to monopolies, and mergers and acquisitions are usually prohibited or regulated. This regulation of economic activity to prevent monopolies is referred to as antitrust in the US—and lies at the heart of the actions of the United States’ government, and the larger trend of competition regulators scrutinising Big Tech across the world. Take the European Union (EU), which has instituted a range of suits against Google, Facebook, Apple, and Amazon over the past decade. In 2017, similar to the Justice Department’s case, the European Commission even fined Google €2.42 billion for abusing its dominance as a search engine.

In India, regulators seem to be hard at work to check the dominance of Big Tech too. The Competition Commission of India (CCI) has instituted multiple cases against Google (including one earlier this month) and is also investigating Amazon and Flipkart over their discounting practices. Facebook isn’t far behind, with the CCI reviewing its investments in Reliance Jio and allegations that the company is abusing its dominant position by offering its payment services on WhatsApp.

All of these state-led lawsuits are generally aimed at offsetting a wide array of harms linked to the dominance of these digital giants through traditional antitrust frameworks. However, traditional antitrust frameworks are also products of a specific time and place in history—one that far predates the information age. As a result, these recent lawsuits have also sparked discussions about how effective they might be in addressing the harms linked to Big Tech platforms in India, and ultimately, consumer interests as well.

Why might we need new competition law frameworks for regulating technology platforms?

Different countries have different competition frameworks in place. The Competition Act, 2002 in India, for example, prohibits anti-competitive agreements, the abuse of a firm’s dominant position, and regulates ‘combinations’ of companies (that is, the mergers, acquisitions, and amalgamations of different entities). Competition regulators—in the Indian case, this role is fulfilled by the Competition Commission of India—are required to assess when to intervene in cases of anti-competitive practices, and to craft remedies or penalise violations.

However, one reason why existing competition law frameworks may not be equipped to deal with Big Tech platforms is because of the current thresholds for regulatory intervention. For instance, in the US, the predominant yardstick used to measure whether behaviour is anti-competitive or not is the consumer welfare standard. This means that usually, antitrust regulators do not intervene unless consumers are harmed. Over the years, this standard has unfortunately been interpreted to focus on price as the key measure of harm.

Simply put: company practices that reduce prices for consumers have generally been permitted by competition regulators in the US.

Reading: @ellerybiddle in @nytimes about digital inequality and Facebook’s Free Basics program https://t.co/dOXWwPVvax pic.twitter.com/pfzL7l98Zm

— Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society (@BKCHarvard) September 27, 2017

In the context of Big Tech companies though—whose services are often ‘free’ for consumers to use—scholars have argued that this interpretation does not cover the anticompetitive effects of the platforms themselves. Why? It doesn’t account for other impacts, such as the company’s overall effect on the economy or the number of competitors it has. This is partly why companies like Google and Facebook faced minimal scrutiny for many years—although their services are free, they hold virtual monopolies in their markets and are able to set the terms for their competitors and with their partners, making it even harder for firms to compete with them.

It’s because these penalties have been ineffective that there are increased calls for more drastic measures to be taken. Some scholars and lawmakers in the US have especially suggested breaking up companies or undoing some of the most problematic mergers, while other methods include taking steps to introduce meaningful changes to how these platforms operate. The EU is also considering amendments to its Digital Services Act that would require platforms to share some data with smaller rivals in some contexts. The logic here seems to be that Big Tech companies’ access to vast amounts of user data—which smaller competitors lack access to—explains their rapidly gaining market share.

You May Also Like: The Non-Personal Data Report: Do We Really Need Another Data Regulator?

In the UK, on the other hand, the competition regulator is pushing for a new regulatory regime for online platforms. The proposed system would have the power to require limited data sharing and interoperability and to undertake other actions such as breaking up some of these platforms.

How have these issues been considered in India?

In India, the Competition Law Review Committee (CLRC) undertook a comprehensive review of competition law in 2018. While it recommended many changes to the broader framework, it found that the law was largely adequate to deal with concerns attributed to digital platforms. One key change that the CLRC has recommended, however—in line with measures being taken in some other jurisdictions—is to consider the deal value of mergers and acquisitions as a threshold for anti-competitive behaviour, rather than just the value of the assets and the turnover of the company (as currently the case).

This is meant to address transactions that are primarily undertaken to acquire data—such as Facebook’s acquisition of WhatsApp or Instagram, for example. In such cases, the company being acquired may not have a high turnover or many other traditional assets, but the transaction can nevertheless have significant implications for market competition.

Now, while a proposed amendment to the Competition Act based on these recommendations is underway, their underlying issues raise another important consideration—that in spite of the CLRC review, the harms of Big Tech companies can’t be currently regulated by the CCI alone. The nature of digital platforms means that the CCI will have to work with other regulators on related issues related to the services offered by Big Tech companies.

For instance, although data privacy concerns in India will fall under the purview of the proposed Data Protection Authority under the proposed Personal Data Protection Bill, anti-competitive behaviours may also lead to significant privacy harms, highlighting intersecting interests. Similarly, the CCI’s actions will also overlap other sectoral regulators—such as the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) when framing regulatory frameworks for ‘over-the-top’ (OTT) platforms (and now the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, which brought digital media content under its purview earlier this week), or the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology, for amendments to the Information Technology Act that impact the structure of digital platforms.

The National Payment Corporation of India’s (NPCI) recent decision to limit the volume of third-party applications on the Unified Payments Interface (UPI) platform—that is, the platform that lies at the core of apps like Google Pay and PhonePe—has implications for competition as well. The NPCI has said that this is to reduce the risk of overburdening the payment infrastructure, and more importantly, to prevent monopolies in the digital payments sector.

India internet companies + startups vs Google has reached CCI as it starts an investigation

Google’s Android Store favouring its own app Google Pay for UPI payments as against other apps (which will be Paytm, Phonepe and now even WhatsApp Pay) is main bone of contention ? pic.twitter.com/UhMFRJRmyh

— Madhav Chanchani (@madhavchanchani) November 9, 2020

The CCI has previously had trouble with jurisdictional overlaps, too. It was engaged in a multi-year tussle with TRAI over jurisdiction when Jio, in 2016, alleged anti-competitive collusion between Airtel, Vodafone, and Idea, leading to significant failures in Jio’s call rates. This issue took years to adjudicate, and was finally settled by the Supreme Court in 2018, although the decision to give TRAI the first instance to investigate has since been criticised.

This is an example of a basic but significant issue—where there are overlaps, how do regulators collaborate with each other? While part of the answer might be to define regulatory boundaries as precisely as possible, that may only be possible to a limited extent in the context of digital platforms given the ease with which their services and reach can often extend to different sectors and markets.

One way to address this is through mandatory consultation processes which require regulators to consult with each other, such as in the UK, where binding memoranda of understanding are in place between relevant regulators. UK regulators for information rights, competition, and communications also launched a joint endeavour to promote collaboration and pool expertise earlier this year, so that they could effectively regulate digital platforms. The country is also considering creating a Digital Authority to provide oversight over the ‘digital environment’, formulate recommendations, and help other regulators coordinate with each other.

Ultimately, some of the most problematic issues with digital platforms are intrinsically linked to their size and market dominance, and competition law is an important tool in addressing part of the problem. Formulating a tailored plan for the CCI to effectively implement the law is essential for effectively regulating digital platforms—and protecting consumer’s interests to boot.

The Bastion is happy to announce a new Technology vertical, where we’ll be covering how the future intersections of tech, policy, and society will affect India’s development journey. To read more of our technology coverage, click here. Interested in writing for us? Click here to read our submissions guidelines.

Featured image: Google’s Poland office, courtesy of Paweł Czerwiński on Unsplash.

[…] https://thebastion.co.in/politics-and/building-antitrust-can-competition-law-protect-us-from-big-tec… […]

[…] https://thebastion.co.in/politics-and/building-antitrust-can-competition-law-protect-us-from-big-tec… […]