This article is the first instalment of our three-part series on how exclusionary colonial conservation plays out in Uttarakhand’s Rajaji National Park. Click here to read part two on how this model impacts the rights of the Van Gujjars living here. Click here to read part three on the larger underpinnings of such conservation models.

On 15 April 2015, the Central government awarded Rajaji National Park the status of a Tiger Reserve—making it the 48th Tiger Reserve in the country and the second of its kind in Uttarakhand.

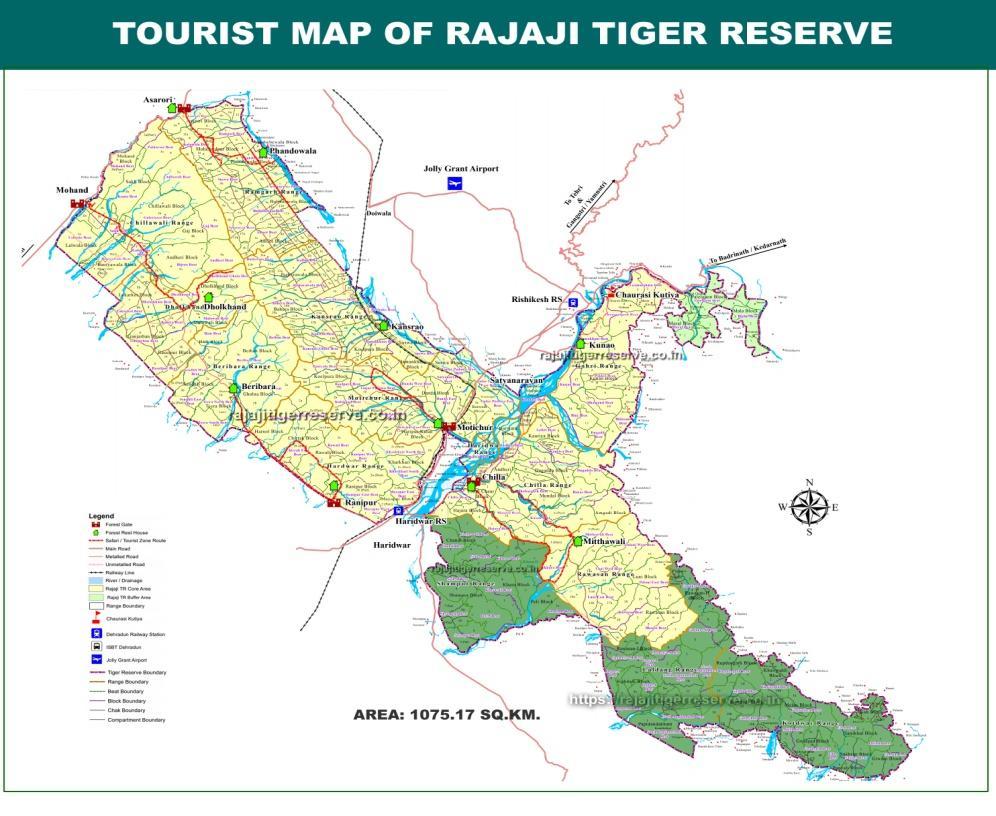

The Park was formed by merging Rajaji National Park’s (RNP) existing core area of 820 square kilometres (sq km) with 255.63 sq km of the Laldhang, Kotdwar, and Shyampur forest ranges. Spread over Uttarakhand’s Dehradun, Haridwar, and Pauri Garhwal districts, the Park now stretches across 1,075.17 sq km. Situated between the Shivalik hills and Rawayan river, with the river Ganga running through its heart, at present, the Park is home to 37 tigers which includes two tigresses.

Over the years, the Park has emerged as the battleground where the State’s colonial developmental conservation practices threaten both wildlife and forest-dependent communities. On the one hand, the Uttarakhand government has uprooted thousands of Van Gujjars living within Rajaji National Park in the name of ‘conservation’. On the other, it has permitted the building of roads and other developmental interventions within the Park, both of which are inimical to conserving the wildlife that lives here.

The Forest Rights Act, 2006 (FRA), recognizes the role of forest-dependent communities in forest conservation, providing them with legal rights over forests and their resources. Yet, in practicing such exclusionary conservation politics, the State apparatus continues to act in violation of these communities’ rights.

In the first instalment of this three-part series, this case study explores how the Laldhang-Chillarkhal road and other development projects have emerged as a battleground between the State’s developmental aspirations and the conservation of one of India’s most critical ecological habitats. Against the backdrop of rights-deprived communities integral to local conservation—like the Van Gujjars described in part two—the complexities and oddities of the power hierarchies dominating protected area governance in India are thrown into sharp relief. The blatant denial of statutory clearances for development projects, and the Uttarakhand government’s apparent apathy for wildlife, pushes us to reinvestigate the role of the State as a ‘guardian of conservation’.

How Forests Became A National Park

The first notification to establish Rajaji National Park was issued in 1983 under the Wild Life Protection Act (WLPA), 1972. The final notification for it was issued only in 2013. The long delay was largely due to the non-settlement of rights of the forest-dwelling communities historically inhabiting the area—and also because the proposal for a tiger reserve here was submitted only in 2010.

Now, the RNP nestles two prestigious wildlife conservation projects: Project Elephant (the Shivalik Elephant Reserve was notified in 2002) and Project Tiger (the Rajaji Tiger Reserve was notified in 2015).

Working directly under the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC), the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) is the statutory authority that overlooks the implementation of Project Tiger across the country [1]. A state-level governing body was formed as per the 2007 NTCA guidelines to oversee tiger conservation. It works closely with the Forest Department and under the Chief WildLife Warden (CWLW) of Uttarakhand.

An additional area of up to 10 kilometres around the boundaries of the Park was notified as the Eco-sensitive Zone on 21 May, 2018 by the MoEFCC. For FY 2021-22, the Uttarakhand government received ₹7.355 crore from the MoEFCC through NTCA for Rajaji Tiger Reserve’s upkeep. These fund allocations are made to arguably support the conservation of this biodiversity hotspot.

Owing to the diverse altitudinal ranges and presence of the Ganga, the area holds critical ecological importance. It houses the highly endangered Asian Elephant and Tiger, over 300 species of both migrant and resident birds, 50 species of mammals, 49 species of reptiles, 10 species of frogs and toads, and 49 species of fish. The Park’s extended areas also house Uttarakhand’s last remaining primordial Terai marshland—Jhilmil Jheel. These 3,783.5 hectares are home to the State’s last surviving herd of Swamp Deer, locally called Barasingha, and were declared a conservation reserve in 2005.

Along with being one of the most diverse wildlife habitats, the area also hosts a diverse forest ecosystem, comprising tropical moist and dry deciduous mixed forests, Khair-Sissoo forests, and alluvial savannah woodlands.

Yet, the preservation of these habitats stands regularly compromised by the wide array of ‘development’ projects underway in RNP—none of which support the conservation of wildlife or flora here.

The Laldhang-Chillarkhal Route: A Road to Destruction or Development?

The Uttarakhand government has been pushing for the construction of an 11.5 kilometre (km) road between Garhwal and Kumaon to shorten travel times. But, this road cuts through the reserve forest area of Rajaji Tiger Reserve (RTR). 4.5 kilometres of this stretch extend from Chamaria Bend to Siggadi Sot, which is the only ecological corridor between Corbett National Park and Rajaji Tiger Reserve. Although this stretch has existed as a kaccha pathway since 1980, the proposal to improve the road by blacktopping was submitted only in 2018. Early petitioners claimed that approvals for the project were bypassed [2].

In June 2019, the Supreme Court taking note of the violation of environmental norms here, put the project on hold and appointed a Central Empowered Committee (CEC) [3] to study the situation. The Court also directed the Uttarakhand government to stop requesting piecemeal permissions to construct the road, and to acquire fresh forest clearances for the entire 11.5 kilometre stretch from the MoEFCC, NTCA, and NBWL.

In July 2019, after inspecting the area, the CEC eventually reported that the construction of the road was in violation of the environmental law. Thereafter, the NTCA requested the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) to study the project in-depth; experts strongly recommended that the “status quo should be maintained on the stretch between Chamaria Bend and Sigaddi Sot.” As per wildlife experts, blacktopping must be avoided in this ecologically-sensitive route, as it would invite heavy and speeding traffic, obstructing the free movement of wildlife.

Yet, in spite of these warnings, in June of 2020, the state received the green light for the elevated road along this stretch from NBWL and the NTCA [4]. The approval was based on three riders laid down by the NTCA: the Uttarakhand government must acquire forest clearances from the MoEFCC, the length of the underpass should be 705 metres, and the height of the underpass 8 metres. These measures are based on the “Eco Friendly Measures to Mitigate Impacts from Linear Infrastructures on Wildlife” issued by the WII that provide comprehensive measures to facilitate the habitat connectivity and smooth movement of wildlife.

Disregarding even these provisions, in July of 2020, the Uttarakhand government presented a modified proposal denying the need for any forest clearances, reducing the length of the underpass to 470 metres, and its height to a mere 5 metres due to geological conditions. The National Wildlife Board rejected the proposal in October citing “high wildlife population density.”

#Uttarakhand govt is likely to de-notify Shivalik Elephant Reserve in #Dehradun to “give way to development work” said state forest minister Harak Singh Rawat @htTweets pic.twitter.com/ogfYjielj2

— Suparna Roy (@suparna_r) November 24, 2020

Yet, by November of 2020, the State Wildlife Board, headed by State Forest Minister Harak Singh Rawat, sanctioned the project. As reported by Times of India, on 25 November of 2020, the Minister had spoken of “feasibility”—further commenting that the Centre needs to review the state government’s amendments to see if they will cause any actual damage. Rawat also spoke of financial concerns—the state government’s proposal suggests constructing the road will cost the exchequer ₹11 crore, while the Centre’s would cost it ₹80 crore. On March 31, 2021, the Uttarakhand government released a fund of ₹2 crore for the road project without the approval of either the NBWL or the NTCA.

On May 28 of the same year, the MoEFCC wrote to the Uttarakhand government asking the state’s Forest Department to acquire forest clearances for the project. On May 31, even the NTCA asked the state government to provide a factual report on the project. Sidestepping the legal necessities of obtaining clearances, on June 11 of 2021 in a meeting of the NBWL Standing Committee (SC-NBWL), Prakash Javadekar (then Union Minister of Forest, Environment and Climate Change) sanctioned the approval for Laldhang-Chillarkhal road. Uttarakhand’s Forest Minister Harak Singh Rawat confirmed that the final length of the elevated animal passage would be 470 metres, with a height of only 6 metres.

All of these developments took place despite the recommendations of the Dhananjay Mohan Committee in 2014, which suggested that a 7.5 kilometre flyover be constructed in a phase-wise manner instead of the Laldhang-Chillarkhal route to facilitate the unrestricted movement of animals.

Although the SC-NBWL had reduced the height of the underpass, in this case, the same SC-NBWL meeting had mandated a minimum height of 8 to 10 metres for the elephant underpass in the 30-kilometre Haridwar-Nagina section of the National Highway 74. As reported by The Indian Express, on July 7, CEC member-secretary Amarnatha Shetty questioned the Environment Secretary, “since the same population of elephants share the habitat involved in both these projects, there can not be different height prescriptions in the mitigation measure (..) [these] can not be decided taking into consideration the cost of [construction].”

On September 16 of last year, the CEC requested the Central and Uttarakhand governments for details on the forest clearances obtained for the Laldhang-Chillarkhal route and the total cost of road construction. The CEC had also enquired about the Uttarakhand government’s reasons for not complying with the recommendations of NBWL, NTCA-WII, or the Dhananjay Mohan Committee. The committee’s question: “what was the scientific rationale behind changing the location of the [Laldhang-Chillarkhal] road? The NBWL had approved the road from Chamaria bend to Siggadi Soth as against the Site Visit Report from March 30, 2021 which mentions an elevated road from Jaspur to Kotwali.”

Such questioning may be too little too late. As per ground testimonies collected by this author and Times of India reports, the blacktopping work for the Laldhang-Chillarkhal route has already started. Such negligence severely questions the role and responsibilities of the CEC and other statutory bodies presiding over the park, highlighting how developmental projects are often built in violation of legal procedures.

How Developmental Projects Impact ‘Conservation’

The emergence of such roads and developmental projects in the area has also put immense pressure on the landscape and conservation efforts. Despite being declared a ‘protected area’ in 1983, the Park has consistently witnessed state-led developmental interventions. National Highway 58 (NH 58), National Highway 72 (NH 72), and the Haridwar-Dehradun railway line are major projects that cut through the Park, bifurcating it into its eastern and western parts.

The widening of the national NH 58 to four lanes has severely choked wildlife movement across the Motichur–Chilla, Motichur–Gohri, and Motichur–Kansrao–Barkot wildlife corridors. This impacts the free movement and population distribution of tigers and elephants—the very species the Park aims to protect.

Known Elephant crossover hotspot, rumble strips to slow vehicle speed, Yellow signboards shout in bold letters to let wildlife have right of way & wildlife rich area- but who cares? Imagine the stress this elephant suffers. NH74, Haridwar. @moefcc @CentralIfs @dodo @wef @PMOIndia pic.twitter.com/DrwI3EyJOv

— Akash K. Verma, IFS. (@verma_akash) July 3, 2020

For example, the Park has only two tigresses, both of whom are isolated and bound to its western flanks because of NH 58. The skewed distribution of tiger population and concentration of male tigers in the eastern parts of RNP has damaged free genetic exchanges, impacting the long term survival of tigers and other coexisting species in the area. As Bishav Pandey, a scientist at WII, reports for Third Pole, “we have photographed about 70 tigers over the past 15 years in eastern Rajaji and none of them moved to western Rajaji.”

In September of last year, a male tiger from Jim Corbett National Park was translocated to the Park’s western regions to produce future generations of tigers here. Initial efforts to translocate tigers failed with either the tigress running away, or the Forest Department unable to monitor and track them once relocated. These ineffective and desperate measures indicate that the natural tiger landscape and its free movement stand fragmented and compromised inside the Rajaji Tiger Reserve.

Over the years, the Chilla hydroelectric power station in the Park’s eastern realms has restricted the access of elephants to the river, ultimately reducing elephant congregations. Near Jhilmil Jheel sits a Bisleri mineral water bottling plant—unregulated extraction of water from the marshland here has resulted in a receding groundwater table, consequently endangering the wetland habitat. The electric fencing of the lake—and the construction of check dams at the exit point of its drainage into the Ganga—has impacted both the water regime and the movement of Swamp Deer.

The state is also overseeing the expansion and transformation of Jolly Grant Airport (located in the same districts as the reserves), for which land acquisition is ongoing. And so, the same park holds many dumping sites for construction debris.

In order to facilitate better wildlife movement, the Supreme Court directed the National Highway Authority of India (NHAI) in 2009 to build an elephant flyover across Chila and Motichur. The construction of four flyovers (each ~0.5 kilometres long) at different animal crossing sites in the Motichur–Kansrao and Motichur–Chilla corridors still remain incomplete. This leaves the western part of the reserve unapproachable for the animals living here.

In January 2019, the National Green Tribunal (NGT), while hearing a petition filed by the Centre for Wildlife and Environment Litigation (CWEL), clearly stated that the tiger population is undergoing local extinction due to the negligence of both the NHAI and MoEFCC in completing this work.

The New Face of Tourism in Developing Uttarakhand

Uttarakhand’s developmental outlook not only crushes the wildlife under road projects and industries, but also exploits them into revenue-generating tourism services. A thorough glance at the government website for the Rajaji Tiger Reserve speaks less of ecology or conservation but more of tourism, elaborating on the luxurious lodging options, safaris, and camping and adventure activities.

By inviting people for a “comfortable stay in the wilderness,” both forests and wildlife are converted into objects of attraction and consumption under the State’s narrative of ecotourism. As a result, the tiger and elephant emerge as the face of the state’s tourism industry, rather than as species in need of conservation. With tourism comes parallel developmental interventions such as the construction of roads and airports.

The desperate push for development at all costs becomes clear with Prime Minister Narendra Modi inaugurating 11 development projects in Uttarakhand on December 4, 2021. These projects, aimed at improving road infrastructure for improved travel and tourism, include the ₹8,300 crore Delhi-Dehradun Economic Corridor comprising Asia’s largest elevated wildlife corridor. The corridor and the tunnelling taking place for it near Dat Kali Temple are in close proximity to Rajaji Tiger Reserve, adding to the adverse impacts wildlife here are already facing.

Why do they want to fragment the western side of the Rajaji too? Where will the jumbos, the leopards and the tigers go?:TOI

Over 104 bird species have been found in this area and is frequented by Elephants from Rajaji National Park.#SaveMohund pic.twitter.com/fCq8wkXb99

— fridaysforfuture.almora (@RAJESHG42923792) September 30, 2021

Such growing stress on wildlife-branded tourism—and the up-scaling of developmental projects in and around Rajaji National Park—raise questions on political and bureaucratic understandings of ‘conservation’. Van Gujjars, whose lives are intertwined with the ecology here, have a keener sense of conservation. However, as part two of this series shows, they too face the receiving end of the State’s model of exclusionary conservation.

This article is based on a detailed case study compiled by the author for the Centre for Financial Accountability.

Featured image: a road passing through Rajaji National Park; courtesy of Prateek Srivastava on Unsplash.

[1] The NTCA was formed on 4 September, 2006, by enabling provisions in the Wild Life (Protection) Act, 1972 through an amendment laid down in the Wild Life (Protection) Amendment Act, 2006.

[2] Responding to contentious approvals being readily granted for the road, in 2019, Bhanu Bansal of the Centre for Wildlife and Environmental Litigation raised the matter in the National Green Tribunal and in the Supreme Court. The petition highlighted how Uttarakhand’s Chief Wildlife Warden continues to seek exemption from forest clearances for development projects and remains in non-agreement to the mitigation measures suggested by NTCA and NBWL.

[3] The CEC report was filed in response to a petition filed by wildlife activist Rohit Chaudhry. The plea demands holding responsible those officials who, without requisite approvals and clearances, allowed illegal construction works and dismantling of roads, bridges, and culverts to take place. It also pled the courts to issue directions to the Uttarakhand government to pay exemplary ecological fines for damaging the critical ecological corridor connecting Rajaji Tiger Reserve with Corbett Tiger Reserve.

[4] The NTCA sidestepped WII’s recommendations and forwarded the project, stating that a 100-metre-long underpass (after every one kilometre of the road) will be built on the stretch. Extending the length of the underpass to 150 metres, the NBWL also approved the project making the total length of the underpasses on the Laldhang-Chillarkhal road 705 metres and at a height of 8 metres.

[…] colonial conservation plays out in Uttarakhand’s Rajaji Tiger Reserve. Click here to read part one on how this model impacts the wildlife the Park seeks to protect. Click here to read part two on […]

[…] colonial conservation plays out in Uttarakhand’s Rajaji Tiger Reserve. Click here to read part one on how this model impacts the wildlife the Park seeks to […]