India’s vast coastline is home to diverse coastal landscapes and ecosystems. These ecosystems also form the backbone of the fisheries sector, which not only contributes to a major share of the national economy, but also sustains the livelihoods of millions of fishers across the country.

However, in spite of the latter, there is only a minimal representation of coastal communities in the debate surrounding the conservation of the marine and coastal commons traditionally used by them. In the face of rampant development and amendments to environmental legislation, this is not only detrimental to fishing as a profession, but to coastal ecologies, environmental democracy, and peoples’ rights too.

But, first, what are the coastal commons and why are they significant to India’s fishers?

“Commons” refers to spaces that are collectively and customarily used or owned by a group of people. These include spaces like community-owned grazing lands, forests, beaches, rivers, and playgrounds, among others. They can be used and accessed by any group of people, yet are often of particular use to homogenous groups-like fishers-in local village communities.

Naturally, fishers largely depend on coastal commons, which include beach spaces, mangroves, inter-tidal zones, mudflats, and sand dunes. Given their centrality to the fishing process, these spaces hold economic, ecological and socio-cultural significance for fishing communities. Coastal commons are not only used to store boats, mend nets, and dry fish, but are also used for religious festivities and leisure. Aside from this, marine fishers naturally require unrestricted access to both waterscapes and landscapes, as the visibility of the sea and the seashore-which are necessary to study daily coastal weather patterns-are vital pieces of information when deciding when to go fishing.

You May Also Like: The Shore Scene: PM-MSY’s Fisheries Development Promises Anything But Sabka Vikas

Unfortunately, India’s vibrant and diverse coastal commons are facing multiple threats. Industrial expansion, commercial fishing, coastal expansion projects, and encroachments have altered the spaces accessed and used by traditional fishing communities. The lack of formal recognition of the customary rights of fishing communities over coastal commons also contributes to their continued marginalisation, and exacerbates conflicts between conservation and development.

Taking into account the existing uses of coastal commons by communities-which are often missed in governmental environmental assessments-could mitigate such conflicts and lead to more democratic and less destructive coastal management practices.

Yet, while there is knowledge of the coastal commons, beyond the surface level, little information on their management exists. While scholars continue to recognise the value of coastal commons, in the everyday context of coastal planning, less is known about the governance of commons by localised community-governed institutions, the local ecological knowledge associated with their use, or the traditional fishing practices deployed.

This lack of tangible information makes it difficult for coastal communities to support their claims to the coastal commons with evidence. Documenting this relatively undocumented domain then is a key first step in the conservation of the commons-and the realisation of coastal communities’ historical community rights over their commons under Coastal Regulation Zones (CRZs).

Encroachment, Evasion, and Erupting Protests in Purnabandha, Odisha

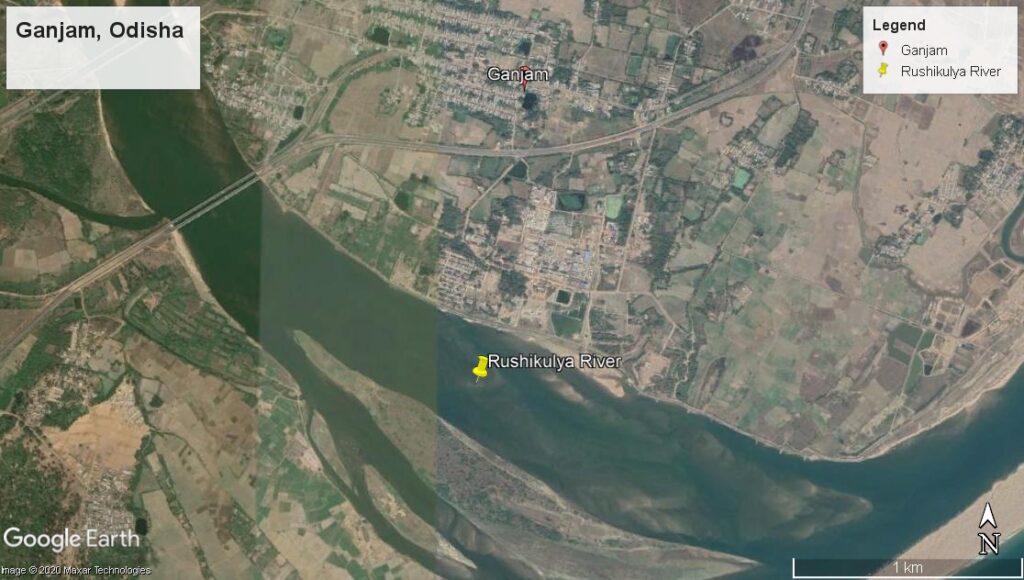

My colleagues and I at Dakshin Foundation recently attempted to carry out such a study in Odisha’s Ganjam district. Based on the study, we identified several threats to coastal commons in Purnabandha, a riverine fishing hamlet, off the Rushikulya river in Ganjam These included degradation due to coastal erosion, pollution, and poor waste management within the community.

However, the encroachment of coastal commons by non-fishing communities, not to mention the regularisation of this practice by the state, remains one of the major threats to the coastal commons of Purnabandha and its adjacent villages.

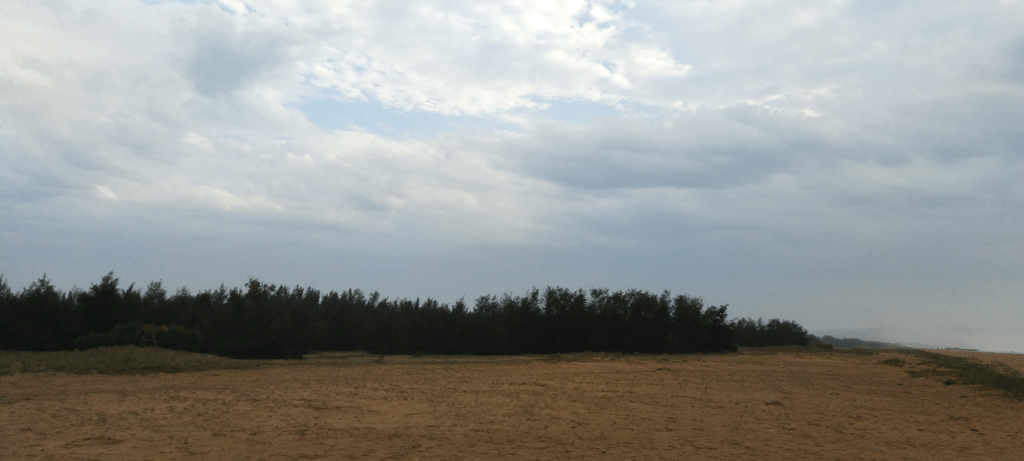

To mark their individual ownership over land, villagers, regardless of whether they’re fishers or not, plant casuarina trees, forming green boundaries [1]. Now, many locals from neighbouring non-fishing communities deliberately plant these saplings progressively closer to the seaside each year, thus claiming more of the shrinking beach commons. To make matters worse, some of these encroachments have also been granted legal ownership rights, in spite of their transgressions. This, coupled with regular sea erosion, has further shrunk the coastal commons available to traditional fishing communities of Purnabandha.

Yet, while these spaces can be considered as the fishing community’s historical commons, from a legal perspective, these lands are formally owned by different private individuals and state entities, including the revenue and forest departments. This non-recognition of the customary rights of fishers over their commons has led to the marginalisation of these communities in tangible ways.

For example, in 2013, the Odisha Forest Department built a turtle interpretation centre in Purnabandha to ostensibly promote turtle conservation in the area. The villagers gave a portion of their common lands-which they earlier used to collect firewood-for the centre’s development, hoping for longer-term benefits such as employment in the turtle conservation teams and better infrastructure for the village in exchange. A few years later, in a rich irony, they were instead denied entry to the lands near the interpretation centre by the department, even to collect firewood, which they had a historical and customary right to do.

In a similar incident, the Executive Officer of the Ganjam Notified Area Council (NAC), the nearby municipal semi-urban body, proposed to construct a tank for the disposal of the town’s waste in 2019. The dumping site was identified near a fish landing site in Purnabandha, a part of the coastal commons where women dry fish for sale throughout the year. The new dumping site had also previously served as an auctioning centre for the fishers, a commons crucial to their livelihood. The decision to dump the waste here was taken without any consultation or knowledge of the local community.

Community leaders suspected this was a deliberate move to preempt any opposition from the villagers. Mangaraj Panda, former member of the Odisha State Coastal Zone Management Authorities (OSCZMA) and Secretary of the United Artists Association (UAA), an NGO working with coastal communities in Ganjam expressed his surprise at the move. “The local community was kept in the dark regarding the dumping of the waste. Why did the authorities hide it? This means it was done deliberately.”

Community opposition unfolded nevertheless, given the gravity of the decision.

The villagers believed that the municipality’s acts would not only hamper their use of the commons, but that the disposal of waste would also lead to the percolation of toxins into the mouth of Rushikulya river, thus affecting the fish catch. Concerns were also raised over health issues among the community if disposal went ahead as planned.

Yet, the municipality started dumping waste overnight. The next morning community leaders called for protests, engaging in a complete standoff against the municipal authorities. “We have formed a ten-member action committee in the village and have written to the authorities against this dumping. Each one of us is even ready to go to jail if the situation arises, but we won’t let the waste be dumped here,” quietly declared Magata Behera, President of the traditional village committee of Purnabandha.

However, where one agency of the government threatened the destruction of Purnabandha’s commons, another came to its unexpected rescue. The latest Coastal Zone Management Plan (CZMP) maps of the Odisha State Coastal Zone Management Authorities (OSCZMA) identify the Coastal Regulation Zones that the waste dump, or commons, would fall under. What they found was telling.

How the Coastal Zone Management Plan Protects the Commons

When the CZMP maps were overlaid with satellite maps using Google Earth, it was determined that the sites where the Purnabandha municipal authorities had started dumping waste fell under the ‘No Development Zone’ (NDZ) of both the 2011 and 2019 CRZ notifications.

NDZs are ecologically sensitive coastal areas where no development projects are allowed. Since the sites fell under the NDZ, even if the authorities wanted to build a waste disposal plant, they would have to do so with the prior approval of the Pollution Control Board, according to clause 5.3 (ii) d of the CRZ 2019 notification. This approval had not been granted to the Purnabandha authorities.

And so, the CRZ’s rather explicit prohibition of the dumping of waste in coastal regions helped in the locals’ fight against the misappropriation of the commons. In a meeting that followed between Purnabandha’s community leaders and the district collectorate, citing the CRZ notification, the community leaders were able to stop the ongoing dumping of the waste.

Drawing on their successes with preventing the waste site, Magata, the President of Purnabandha’s traditional village committee, notes that “Many encroachment disputes could have been avoided if we had a map of our commons authorised by the panchayat. Every coastal village in Odisha should come up with their own maps demarcating their commons. Fishers should also be made aware of their rights and regulations like the CRZ-many of us are unaware of them.”

Using the CRZ for good: Fishing Communities in Action

Clearly in the case of Odisha then, raising awareness on laws and other mechanisms to defend one’s rights is the call of the hour. Lessons can be drawn from other enterprising fishing communities across the country.

For example, while fishers in Odisha remain somewhat unaware of the CRZ and its implications on their lives and livelihoods, fishers in Tamil Nadu have been leading the way by wielding the law to the benefit of both communities and the environment. Fishers in Tamil Nadu have carefully documented coastal commons, their uses, and how they access them using a combination of tools ranging from hand-drawn maps, to satellite and revenue maps.

These maps have been successfully incorporated into Tamil Nadu’s CZMP maps as well. This has proven to be invaluable in coastal Chennai, where multiple coastal projects threaten the region’s unique coastal commons and the communities dependent on them.

Coastal community institutions clearly have a major role to play in protecting the commons. They can be strengthened if they are helped to actively engage with various environmental laws. Beyond that though, increased representation of fishing communities in the various state coastal management bodies can also ensure that the concerns of fishers regarding the alienation of commons are better addressed.

For example, while there are provisions in the CRZ for the representation of leaders of traditional coastal communities, these often remain paper promises. Mangaraj Panda believes that the leaders of coastal communities who are represented in the DLCs (District Level Committees) of the CRZ, should be elected by the community themselves. “Often the authorities pick someone with a vested interest from the community for the meetings,” says Mr. Panda who is himself a part of the DLC in Ganjam. He added that the DLC should ensure that the community is made aware of various coastal rules and regulations.

The community resistance against waste dumping in Purnabandha shows that increased local participation from communities is indispensable in strengthening their claims over the use and conservation of commons. The state should also ensure the inclusion of coastal communities in decision-making processes for better management and conservation of coastal areas.

The Future of the CRZ and the Commons

Given these tangible benefits, the recent dilution of the CRZ notification in 2019 (CRZ 2019), and the controversial draft Environmental Impact Assessment 2020 (EIA 2020) pose grave threats to the commons.

For instance, in CRZ 2019, various zones such as CRZ 1, CRZ 2 and CRZ 3 have been recategorised so as to allow activities such as eco-tourism in ecologically sensitive areas, land reclamation, and the development of hotels, housing, and tourism facilities near the shore. This would mean an increased threat to not only the coastal commons, but to the very existence of the communities themselves.

You May Also Like: Shrinking Negotiations: How the Draft EIA 2020 Is Affecting Public Consultations on Development

In the case of the EIA 2020, as various civil society submissions point out, there is an increased push to industrialize coastal areas by including Coastal Economic Zones (CEZs) under Notified Industrial Estates (NIE), which face minimum public scrutiny. The draft has also allowed activities such as fencing, shed construction, land levelling, and geotechnical investigations to take place prior to their receiving an Environmental Clearance. This can lead to the appropriation of commons without the consent of the communities dependent on them, and could also have severe ecological impacts in the case of wetlands and mangroves. The drastically reduced scope of public consultation in the EIA, coupled with the fact that most of the information regarding the projects are not available in local languages, only add insult to public injury.

Evidently, the new draft EIA coupled with the recent amendments in the latest CRZ notification push for rapid industrialisation at the expense of local voices. There is a need to strengthen vulnerable natural resource-dependent communities, like those of Purnabandha, by making them more aware of laws concerning resource governance. Only then will the coastal commons continue to thrive with the support of the communities that understand them best.

With inputs from Vineetha Venugopal and Aarthi Sridhar. | Views expressed are personal | Featured image courtesy of Vineetha Venugopal.

[1] Casuarina equisetifolia is an exotic species that was widely planted by the forest department along the Odisha coast, ostensibly to prevent damage to lives and properties from cyclones and storms.

Forget all costal zone CRZ etc, The Goverment the Fisherman including NGO’S Won’t raise their Voice against the Poluting affluent water being discharged into the sea without filtering that’s more dangerious than anything at the moment an needs to be addresed on top prority at present. Fisherman cry for no fish they don’t address this major issue , water polution from industrial zone, residential zone all is dumped in open Sea without treating

How can all keep a blind Eye on this detremental issue.

The fishermen are facing many problems. CRZ Rules are always being violated by vested interests in connivance with politicians. They are only interested for their personal benefits, least bothered about environment and poor fishermen.