Co-authored by Kaushalya Misra & Avantika Bunga

“What is the problem with saying Vande Mataram? We are saying thank you to mother earth? What is wrong with that? I would have understood if we were praying to some God or Goddess. But nothing is wrong with this. It is very secular. Only ‘these people’ will have a problem.”

— Ashvin*, a parent from the Eastern suburbs of Mumbai

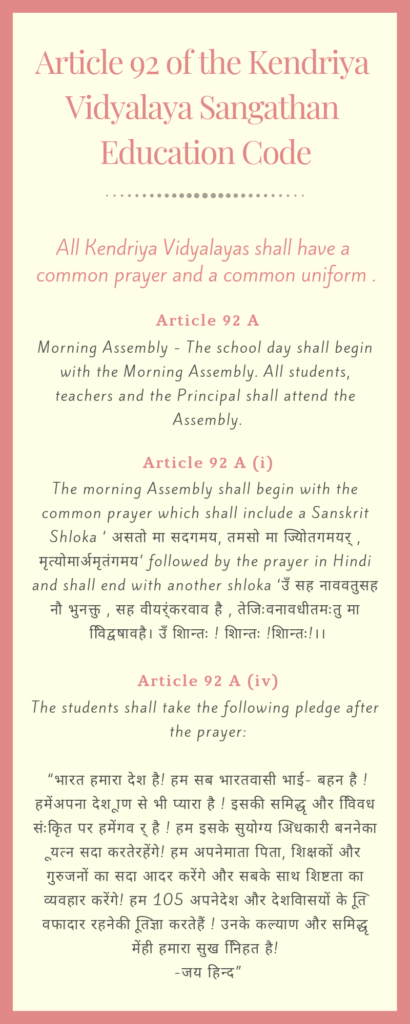

Students of all age groups stand in neat files, with their hands respectfully folded and eyes closed while reciting their morning prayers. Despite belonging to diverse ethnicities, this is a familiar occurrence for students across India every morning, during their school assemblies. This exact routine of reciting Sanskrit (and sometimes Hindi) prayers is being questioned in an ongoing Public Interest Litigation. A five-judge bench of the Supreme Court of India is set to determine the constitutionality of such practices in state-recognised or state-funded educational institutions, like the Kendriya Vidyalaya (KV) schools.

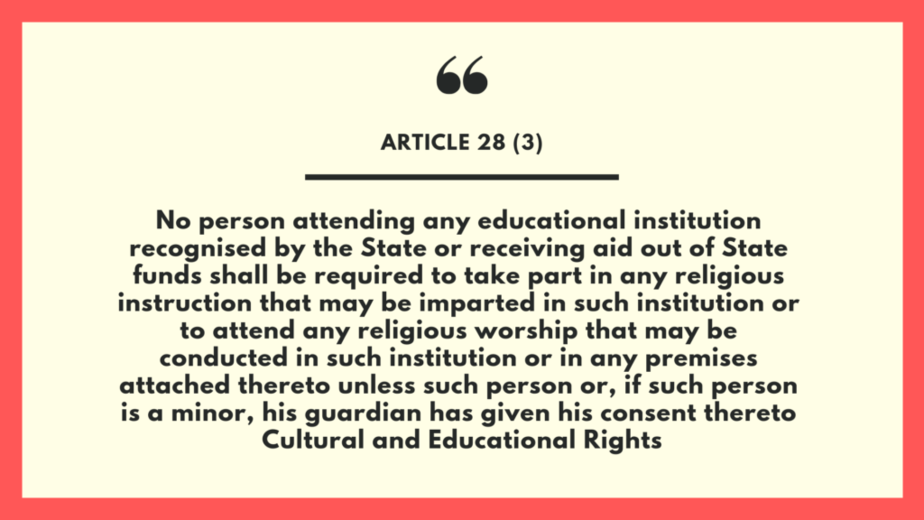

The SC has previously sought to clarify that the interpretation of Article 28 (3) is limited to protecting the individual freedom of conscience of any person attending a state-affiliated educational institution by ensuring that they are not compelled to partake in ‘religious instruction’ or ‘religious worship’.

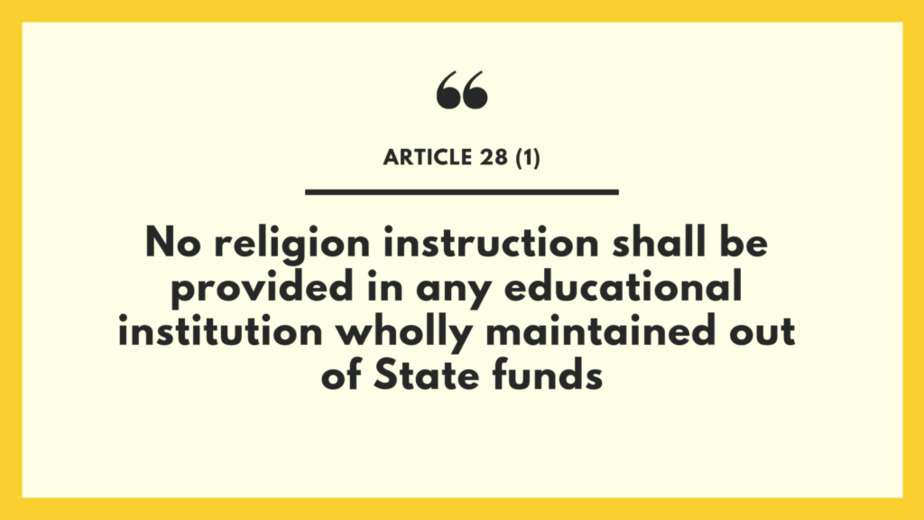

This is not the case in Article 28 (1), which categorically prohibits ‘religious instruction’ in the case of institutions wholly maintained out of state funds. The petitioner in the KV case claims that the practice of chanting Sanskrit and Hindi prayers constitutes ‘religious instruction’ under Article 28; therefore, it ought to be prohibited. No submissions have been made in relation to ‘religious worship’ that is separately covered under Article 28 (3).

Vice President M Venkaiah Naidu in Delhi: Other countries are doing research on Sanskrit, Vedas and Upanishads. We’re feeling shy to even touch them, in the name of secularism. How is secularism connected with these things? pic.twitter.com/mbyWyihPrf

— ANI (@ANI) January 21, 2019

In fact, the courts are yet to interpret what “religious worship” even comprises of. So, in the KV case, the bench’s interpretation of ‘religious instruction’ and ‘religious worship’ will be pivotal in deciding whether the recital of Sanskrit shlokas or Hindi prayers qualifies as either. Even if students are free to forego these prayers, it is conceivably difficult for a child to oppose their peer and school administration during assembly events. Clearly, even beyond state-funded educational institutions, there may be compelling ramifications of these routinized ‘neutral’ prayers on students and their parents, with equally disruptive opinions on either side of the commotion.

Much Ado About Nothing?

Counsels representing the Union of India in the KV matter have focused on the ‘universality’ of the prayers sung in KV schools, going so far as to highlight that certain verses of the Mahabharata also appear in the Supreme Court emblem without detracting from its secularity.

Some educators also echo this line of reasoning, emphasising the all-encompassing nature of Sanskrit shlokas and their religious neutrality. A member-in-charge of the Gurukula project led by Mumbai-based charitable trust Bharatiya Shikshan Mandal, Acharya Ramchandra Bhat believes that reciting Sanskrit prayers could generate academic interest in the language. Citing the continued linguistic and historical relevance of Sanskrit in academic institutions around the world, Bhat dismisses the matter of reading of Sanskrit prayers and shlokas in government schools as a non–issue, lamenting that “this political context did not exist” until recently.

This conflation becomes interesting when the Supreme Court while recognising the protections under Article 28(1) and 28(3) with regards to imparting “religious instruction” in state-funded educational institutions, sought to distinguish instruction from “religious education” or the “Study of Religions”. The ruling stated that only the latter was both permissible and important in order to educate and create awareness regarding the different religions of the country.

The Court’s call for a constant vigil to avert the “potent danger of religious education being perverted by educational authorities whosoever may be in power by imparting in the name of ‘religious education’, ‘religious instructions’ in which they have faith and belief”, may be particularly relevant in this context.

#KVPrayerDebate Is reciting ‘Asato Ma Sad Gamaya’ in Kendriya Vidyalaya’s prayer peddling Hinduism? Is Prayer in Sanskrit = Promoting Hinduism? 2 judge SC bench refers matter to Constitution Bench. How is reciting secular prayer in the most scientific language unconstitutional?

— Anand Narasimhan (@AnchorAnandN) January 28, 2019

While there exists a strong inclination to separate the system of Sanskrit prayers from any religious connotations, Dr Sthabir Khora, Professor at the School of Education at TISS Mumbai, tells us that the study of Sanskrit “is of immense importance to those who study and analyse scriptures,” but implementing Sanskrit prayers and shlokas at school could imply a form of cultural hegemony. He maintains that “it is imperative to make a distinction between Sanskrit as a language and Sanskritization. Sanskritization is the glorification of Brahmanical values.”

Professor Khora’s argument alludes to those who choose (and have the privilege) to look the other way when faced with the religious undertones of Sanskrit shlokas. The well-documented control of Sanskrit by Hindu upper castes and its usage in canonical Hindu scriptures must be considered when matters of constitutional rights and secularism are in question.

Private Schools are Hymning Along

According to Professor Khora, the lack of opposition to the proposed changes in KVs could represent “a fear among parents and students that they would be victimised or discriminated against by the authorities”. Yet, despite the question of constitutionality vis-à-vis Article 28 arising only in state-funded or state-recognized schools like Kendriya Vidyalayas, private schools are privy to the same passivity. Once privatised, the management is within their rights to conduct prayers of any chosen religion(s). This can create tense learning environments for students and their parents who belong to minority communities. Given the political climate, even private religious schools’ open affinity for certain prayers has become scrutinized for being majoritarian, bolstering the stakes of the KV Sangathan’s assembly debate.

“Sometimes, my younger son comes and tells me, “Ammi, today I murmured our prayers and did not do the other prayer.” I tell him that’s OK because your faith need not be on display, you can stick [to your own faith] in this way.”

A mother to a six-year-old boy studying at a private Hindu-trust-run school in a poor suburb of Eastern Mumbai, Salma* echoes the sentiments of many parents who come from non–Hindu communities. Uneasy conversations with their children regarding Hindu religiosity is a common phenomenon and one that parents have learnt to deal with in their own ways. Salma hesitantly admits that she has considered putting her son in a Madrassa instead, but this is a better school, which leaves her with little choice. Casually using India as a euphemism for Hinduism, she says “but see, this is India so we have to accept Indian prayers and love every part of it. Our religion teaches us that.” There is a sense of mute resignation and hopelessness, similar to the one raised by the petitioners against shlokas being imposed in Kendriya Vidyalayas.

For some, this discomfort extends to even chanting “Vande Mataram”, which was used as a Hindu-nationalist slogan and also famously acknowledged by Rabindranath Tagore as being dedicated to the Hindu Goddess Durga. Such deference is considered to be at odds with the teachings of Islam, wherein Allah alone is prayed to. For parents who are otherwise accepting of Sanskrit assembly prayers, the additional chants of “Om” and “Jai Hanuman” expected of their children pushes their discomfort and the envelope for their for tolerance.

Article 28 of the Indian Constitution does seek to address this growing discomfort by clearly desisting any students’ compulsory attendance of ‘religious instruction’ or ‘religious worship’ in state-affiliated educational institutions. The PIL in question could be an indicator of larger questions for Indians to ponder; for example, is the bone of contention to do with the language used and the meaning imparted by the said prayer? If the language of reverence were to be changed, which one would be truly universal for Indians?

There are no binary answers to these questions, and rightly so. Perhaps we need to rethink the ethos of what it means to pray communally in a school assembly in itself, because any prayer may be inherently devout and religious. After all, with India’s multiple religions and diverse conceptions of Hinduism in itself, the KV litigation has the onus of weighing increasingly straitjacketed understandings of what it means to be Hindu while maintaining a vision for a secular, tolerant and equal Indian citizens.

*Names have been changed maintaining social markers.

Featured image courtesy Joe Gonzalez|CC BY-ND 2.0

Teach for India is currently accepting applications for the 2019-’21 batch. The deadline to apply is 24th March. Apply Here

[…] You May Also Like: Indian Students’ Silent Hymns: Of Sanskrit Prayers in Secular Schools […]

[…] READ ALSO: Indian Students’ Silent Hymns: Of Sanskrit Prayers in Secular Schools […]

[…] The National Curriculum Framework (2005) states the importance of integrating a culturally sensitive pedagogy while imparting education. Yet, currently, the State in its attempt to address ST educational outcomes in the residential educational model ends up both directly and indirectly encouraging assimilation into a larger hegemonic educational culture. […]