This is the first article of a three-part series on sustainable consumption and food security in India, supported by Pristine Organics. Click here to read part two and part three.

Last spring I decided to become a vegan. I was influenced by documentaries like “Food, Inc.” and “Cowspiracy” that depicted the unsustainability of American eating habits and the detrimental environmental impacts of consuming meat sourced from factory farms. Although I was living in India and eating a completely different diet from the Americans on my screen, I was still compelled to take up a vegan diet, thinking it was the least I could do to be sustainable and environmentally conscious.

It didn’t last for very long.

Still craving dairy products and the taste of meat, I was simply replacing my previous diet with heavily processed and extremely expensive dairy and meat alternatives, that were neither affordable nor environmentally friendly.

While how we define veganism is personal, ultimately, there is more to sustainability than conscious consumption. We need to take a step back and ask ourselves, what does it really mean to be sustainable and environmentally conscious, specifically in India?

Too often, our consumption practices are highly individualistic, in that we forget to ask ourselves what type of change is needed to achieve a sustainable food system in the first place. Can we move beyond an increasingly popular imported model of sustainable consumption to better address India’s food issues?

But, what does ‘sustainable consumption’ mean in the first place?

Sustainability has become a buzzword, something used to describe sectors as diverse as clothing, tourism, economic development, and of course, food and agriculture [1].

Provoked by stories of famine and rapid population growth in South Asian and African countries, the concept of ‘sustainable food production and consumption’ first gained traction in the United States in the early 1970s. The US’ recognition of the failures of the energy-intensive Green Revolution also led to a growing environmental consciousness—which led to the birth of ‘sustainability’ as a discourse.

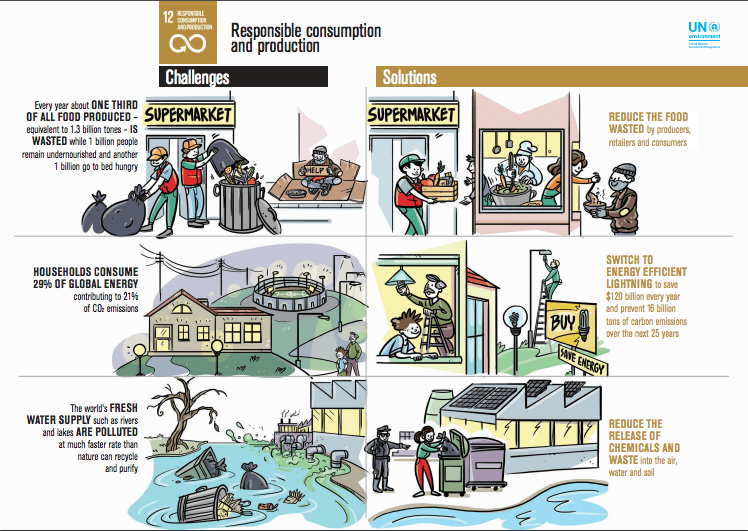

Ideally, sustainable consumption means that our food practices meet the dietary needs of today in terms of nutrition and satiation, without compromising the needs of future generations (especially regarding ecological concerns). Additionally, a crucial part of sustainability is that sustainable consumption must enable socio-economic justice for everyone involved in the supply chain, as much as it addresses consumer and environmental concerns.

From the early 90s, the ‘sustainable consumption’ began to pick up in India as well, but how does this discourse really unfold in our own imaginations? What do we think constitutes sustainable consumption?

There is a growing push towards sustainable food production and consumption, both at a governmental and personal level, so as to stabilise uncertain food supplies across the country. For example, the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) launched the “Save Food, Share Food, Share Joy” initiative in 2017 to “promote food donation, stop food waste and food loss in the country” and reach the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals for “sustainable consumption and production patterns.”

So, at the state-level, sustainability in India is primarily understood through the lenses of food security—which is when “people, at all times, have physical, social, and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their food preferences and dietary needs for an active and healthy life.”

This line of thinking is ideal, as it envisions food for all—yet it is at odds with the realities of some popular conceptions of sustainable consumption produced by certain sections of Indian society. For Indian consumers, sustainability ends up being a term with a heavily contested meaning.

So, what are these ‘popular’ conceptions of sustainable consumption and production then?

Popular ideas of sustainability are best witnessed in a practice gaining much traction: the organic food movement, where a coordinated push towards eating more environmentally conscious produce is taking place. Organic food is undeniably better for the environment as organic farmers use natural fertilisers such as compost or animal manure, avoiding the harmful chemical-laden herbicides and fertilisers popularised during the Green Revolution.

However, organic food, ironically once abundant thanks to indigenous cultivation practices, has become exceedingly expensive as certified organic food incurs more input costs and demands premium prices when sold in high-end farmers’ markets or organic stores. There is also less financial support for the strenuous procedures that farmers go through to become certified organic producers.

On the other hand, institutional support for conventionally grown food through subsidies for input costs makes it artificially cheaper and more affordable, consequently shrinking the market for organic food. Organic food then becomes a niche product sold at organic farmer’s markets or stores. Such initiatives, although commendable in their efforts, show eating organic food is unviable for everyone—produce is sold at much higher prices than conventional products found in local markets, ultimately affecting its ability to be sustainable at a larger scale.

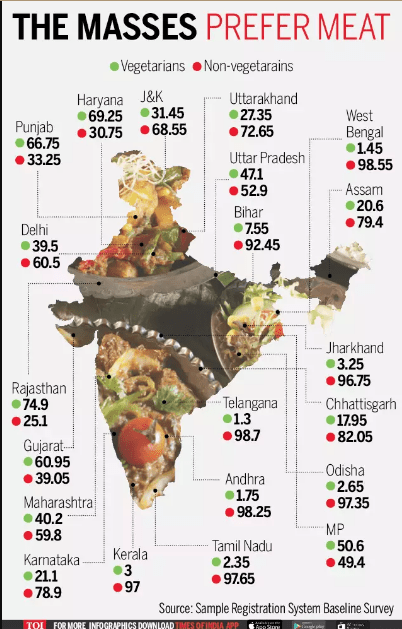

Another practice that has gained popularity in discussions of sustainability is becoming vegan or vegetarian in the interests of the environment. These discussions are spurred by India’s rising consumption of meat and dairy—the 2012 Household Consumption Reports from both urban and rural areas showed increased spending on milk, meat (particularly poultry), and eggs over the years. Between 2005 and 2011, 37% of total agricultural output growth came from animal products, showing a rise not only in consumption, but in production too.

This growth has led to environmental concerns around mass meat production that are warranted and must be addressed. In India, chickens are raised in cramped, dirty factory farms to produce cheap meat and eggs for consumers. Beyond ethical concerns, manure runoffs into nearby water bodies or the release of odorous gases create concerns about negative environmental impacts.

Consequently, many advocates for sustainable food consumption posit that keeping meat and meat products off the table is a necessary step towards environmental sustainability.

However, pushing vegetarian or vegan diets on India’s general population fails to account for the rich diversity of food practices in the country and the lack of availability of nutritious food options for some communities. Veganism, says public health practitioner Dr. Sylvia Karpagam, “is neither environmentally sustainable nor nutritionally sufficient [in India]” as the production of plant-based food alternatives are “very centralised, commercialised, and company dependent.”

In this regard, meat consumption for many agricultural communities may actually be less harmful to the environment. Many meat products are still procured from farm animals that are incorporated into pre-existing farming systems and provide important local nutrition resources for many. For example, cows are still used as farm labour and also consume shrubs that aren’t edible for humans, converting them into highly nutrition-dense food through dairy products or meat.

Vegan products “are also nutritionally inadequate and use cheap soy and corn, with a lot of additives and chemicals to make it last longer in storage, making the cost inevitably higher,” says Dr. Karpagam. Therefore, advocating for vegan diets is not sufficient to address the food crisis in India and are exclusive practices that don’t take into account the dietary needs of the general population, many of whom are still under-nourished.

With regards to vegetarianism, it is necessary to address the social politics of meat in India. Meat has played a crucial role in shaping political ideologies, and is especially used by dominant castes to criminalise meat-eating communities. Hindu nationalists have also successfully campaigned for ‘beef bans’, which discriminate against beef eaters and distributors. For many, cows are not only necessary for nutritional needs, but also as major sources of income, particularly for Dalit and Muslim populations.

Such ideologies have had dire consequences as communities are threatened for their food choices while receiving no state support for viable nutritionally dense alternatives. Pushing for vegetarian diets across the country denies the survival of food cultures that heavily rely on meat. More importantly, they shift the attention away from unsustainable systems and politically motivated food policies, by placing the emphasis on diets themselves.

What are the implications of these diet-centric ‘sustainable solutions’ on food consumption and production in India?

Consumption patterns are changing: we’re moving away from traditional, locally-sourced diets, and increasingly relying on packaged and processed food from highly industrialised (and environmentally destructive) food factories.

This has led to a social and cultural shift in the way food is perceived—and consumed.

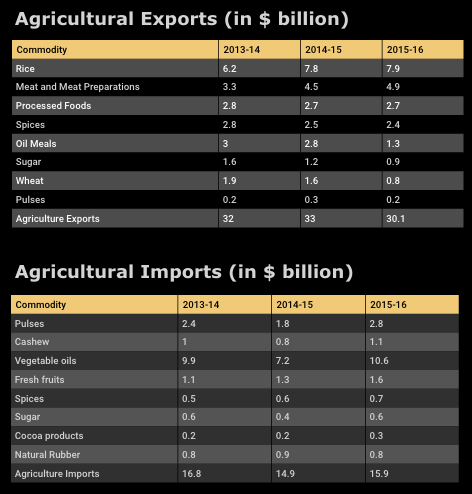

Consider the fact that in recent years, there has been an increase in imports in food staples such as pulses and edible oil as well as vegetable and animal-based fats, and energy-dense, processed foods (see table below). Such trends have changed the way many Indians eat, especially how the middle and upper urban classes eat: large multinational food companies now hold weight in the Indian food market be it through their products, or fast-food chains.

For example, I have admittedly become better at cooking European dishes, involving ingredients like tomato sauce from Funfoods, Disano’s pasta, and Amul cheese sourced from distant factories, than traditional Mizo dishes like saum bai which involves locally sourced ingredients like vegetables and pork fat.

But, not only are most of these products heavily processed or preserved in factories, they are often high in carbohydrates and sugars, consequently factoring into India’s growing problem of overnutrition and obesity. We are so used to seeing these products on supermarket shelves and consuming them, that our ‘sustainable food’ solutions end up revolving around how to make products alone ‘healthier’ (even as they incur high food miles while being grown.)

As a result, we often don’t question how our own consumption might be shifting attention away from prioritising self-sufficient agricultural systems and environmentally sustainable domestic industries.

And so, these popular conceptions of sustainable food practices are largely centred around the consumer’s interests and concerns. Yet our understanding of popular here comes from Western initiatives which are criticised as upper and middle class-specific even in the West. In the Indian context too, the framing of sustainable food and consumption has become deaf to India’s socio-political and ecological realities, and have been problematised as initiatives of upper-class, urban consumers.

As Sunita Narain, an Indian environmentalist and advocate of sustainable development notes, environmental struggles in India have started to reflect Western ideals of “middle-class” environmentalism which aim to will away problems through money and new technologies. New methods of achieving sustainability are often too expensive, with Narain adding that “In our world, if you cannot make it affordable, it will not be sustainable.” Although Narain’s discussion is more focused on sustainability in its total environmental concern, similar conclusions can be drawn about popular conceptions of food sustainability too.

But, why should sustainable food solutions in India account for everyone? India’s glaring food crisis bears some answers

There’s a reason the government perceives sustainable consumption in terms of food security.

While India is one of the largest food producers in the world, high rates of undernutrition and malnutrition prevail. The Global Nutrition Report 2020 indicates that 37.9% of children under 5 years in India are stunted (low height for their age) and 20.8% are wasted (low weight for their height). Additionally, the 2020 Global Hunger Index reported an undernourishment rate of 14% in India, with the country ranking 94th out of 107 countries.

COVID-19 (and the ensuing lockdowns) have only worsened and exposed India’s vulnerable food supply chains and distribution systems. Sarbati Devi from Punjab conveyed her struggles to feed five grandchildren on her own to The Indian Express. When schools were open, most of her grandchildren received at least one full meal a day from the Midday Meal Schemes. As schools closed due to the lockdowns, Sarbati Devi only received a couple kilograms of rice and wheat and ₹200 for cooking costs through the Midday Meal rations. These quickly ran out, leaving her family to grapple for food without additional support from the government and no fixed income.

Simultaneously though, malnutrition is mirrored in the opposite problem of over nourishment. 21.6% of Indian women and 17.8% of Indian men are either overweight or obese. Why? In part, due to India’s increasing consumption of non-cereal based foods such as milk, dairy products, or meat, and unhealthy foods such as fast food, processed food, or sugary drinks.

Quite literally, the Indian population is paradoxically stuffed and starved at the same time.

To a certain extent, this food crisis—defined by unequal access to food—is the result of multiple factors. These include inefficient and unsustainable practices in agriculture and the food supply chain, the failure of state-led food policies, as well as shifts in consumer behaviour. Despite India’s agricultural productivity, India is still far from being self-sufficient in its food production, even as it still exports produce to foreign countries. The remaining produce is also unevenly distributed, with state-led food policies having failed to provide the country’s growing population with enough nutritious food. This only increases unequal access to food.

One such state-led initiative is the 2013 National Food Security Act, launched to provide at least two-thirds of the Indian population with access to the Public Distribution System (PDS). Under the PDS, anyone who holds a ration card can access staple items like rice, pulses (dal), salt, sugar and local millets at heavily subsidised prices.

However, studies have shown that while the Act has been indeed been transformational, a large proportion of the food that is promised never reaches the recipients. In 2012, Sowmya Dhanaraj and Smit Gade estimated that in Tamil Nadu, for every 5.43 kilograms of rice distributed by the government through the PDS, only 1 kilogram reached those in need, while for every 8.21 kilograms of sugar distributed, only 1 kilogram was actually received by card-holders. Even with the introduction of Aadhar based biometric authentication, studies show that there has been no significant increase in the value of food distributed and received by recipients of the PDS.

Requiring Aadhaar to obtain PDS benefits in Jharkhand led to considerable reduction in leakage, but also led to non-trivial increase in exclusion error and transaction costs for beneficiaries. New paper at: https://t.co/NjenifP1dy; @htTweets op-ed at: https://t.co/NnQcd279RI pic.twitter.com/MJtAq9rB2C

— Karthik Muralidharan (@karthik_econ) February 17, 2020

Despite the elitist overtones of some initiatives for sustainable consumption habits, they are neither irrelevant nor non-negotiable. However, at an individual level, we must contextualise sustainability through grounded initiatives that keep in mind India’s unique food crisis, as well as its rich culinary cultures and agricultural traditions.

Beyond just consumption then, the wide-scale sustainable production and distribution of nutritious food seem to be the first necessary components of a resilient and well-fed population. This also needs to be done keeping in mind the preservation of ecologies that can continuously provide food.

But, how do we begin to understand these layers? The just treatment of everyone involved in the process of production and distribution is an important starting point.

About the Sponsor: Pristine Organics was founded to bridge the gap in nutrition and reconnect us to foods that sustain and nourish us. Our products come from ecologically mindful farming and processing methods that are healthier, both for us and our planet.

Click here for FAQs on how we run sponsored content at The Bastion.

Featured image via Pxfuel.

[1] Spindler, E. A. The History of Sustainability The Origins and Effects of a Popular Concept. Sustainability in Tourism, 9–31, 2013.

[2] Guthman, Julie. Agrarian Dreams: The Paradox of Organic Farming in California. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004, pg. 6.

[3] Ibid, pg. 7.

Best Organic food Products Brand in India Nimbark Foods is India’s top-rated organic food brand that provides 100% organic foods products to consumers.

Buy organic food online from the Nimbark Foods website. You can choose from a wide range of organic foods products like Arhar Dal, Roasted seed, Roasted puffed wheat Moringa powder, Besan, etc.

[…] consumption and food security in India, supported by Pristine Organics. Click here to read part one and part […]

[…] consumption and food security in India, supported by Pristine Organics. Click here to read part one and part […]

Useful information thank you