This article is the first instalment of a two-part series on why learning traps ensnare children in cycles of poor academic performances, and what can be done to dissolve them. Click here to read part two.

“…the teacher still feels accountable for completing the prescribed syllabus (..) Children who fall behind stay behind as the rest of the class moves ahead. Most primary school teachers take the least risky route by concentrating on those children (..) who can cope with the syllabus.” —Dr. Rukmini Banerjee, CEO, Pratham Education Foundation

Imagine this-you’re betting on a forty hurdle horse race. If the horse successfully crosses all the forty hurdles in one go, it wins. It gets money, respect, and fame. If however, a horse reaches only till the middle, it’s as good as useless. This horse receives no training, no practice, and no second chances. What kind of horse would you bet on? In all likelihood, it would be the one that shows early signs of outstanding performance.

It will probably not come as a shock to you that India’s education system somewhat functions like this hypothetical horse hurdle race. Who’s placing the bets? Anyone who has the power to invest anything in the horses–teachers, school leaders, and parents. Who are the horses? That’s easy, the students.

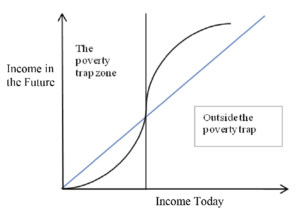

Now, we’ve all heard of poverty traps–essentially, when the minimum income level required to save and invest is so high, that some people simply cannot escape it. Have we created similar learning traps in our education system, where a small learning disadvantage gradually becomes a much bigger handicap that students can’t break out of? Do these learning traps feed into intergenerational poverty traps?

Poor Education, Poor Economics

In Poor Economics, Nobel laureates Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo use an “S-shaped” curve to depict the impact of poverty traps. Individuals with low incomes are marked to the left of the inflexion point, and thus find themselves in a ‘trapped’ zone. An extremely low income marks an inability to invest in one’s sustenance and health, which leads to low incomes in the future as well.

Now, a person could break out of a poverty trap by getting someone to invest in them, say, through a loan. But at low-socioeconomic levels, and given the imperfect nature of economic markets, they are difficult to come by and the person remains trapped in a cycle of poverty.

Similarly, a learning trap is any mechanism that reinforces low learning levels. Students with learning levels below desired competitive levels, find themselves in a zone where neither teachers nor parents are ready to invest time, money, or attention in their education. This neglect only increases with time. How exactly do these learning traps pan out in the classroom and home?

Where Does the Rot Start?

Everyone remembers that one student at school who always read out loud in class, spoke during assembly, and was selected to participate in all the competitions. Was that one student really the only person good at everything?

Not really, but that’s often how people in schools behave.

In my experience, teachers ask questions to children who they know can answer confidently, and show little patience when less confident students try to work questions out. A school leader from a school in Pune routinely tells her teachers, “Everyone cannot do it. You cannot teach basics or concepts to everyone, so don’t even waste your time. The rest of them just mug up the answers.”

So, teachers tend to view the education system as a binary system. A child can either do it or they can’t. The ‘rest’ of the students are ignored and remain stuck in a trap of low expectations, low motivation, and low performances. Such attitudes play out in how parents respond to their children as well.

How Parents Inadvertently Enable Learning Traps

During my experiences as a TFI fellow, I notice that parents, especially from the lower-middle classes, are strained for time and resources and thus lack the knowledge to hold teachers accountable. Ensuring their child’s attendance in class and tracking homework are some of the gaps in their engagement with schools. So, when a teacher squarely blames a child for not doing enough, or labels him as “stupid”, they often don’t have the wherewithal to question them.

Believing these statements, they often end up giving up on their child’s academic future too soon. In several cases amongst siblings, as Banerjee and Duflo corroborate in Poor Economics, parents choose to focus on the child that shows better academic promise. Sometimes their own beliefs about themselves come in the way of expecting more from their children.

This phenomenon is highly visible in Teach for India classrooms, where initially parents of certain low performing children seem to have given up on their wards. Yet, if because of the persistence of a teacher a child’s grades start improving, parents start tracking their progress more, and investing more in them to boot.

For the most part, though, parents see that their children stay in school only till they cross the age of 14, the upper level of the RTE mandated ages between which all children should be educated. By doing so, they hope that their children gain some sheepskin effects from staying in the classroom. The drop-out rates at the secondary school level, of ~30% attest to the same.

What Causes Learning Traps to Manifest in the Classroom?

Given this state of affairs, the students who’ll drop-out in the future are etched into stone way before the judgment day arrives. Looking at the simple parameters teachers go by, one could walk into a 4th or 5th-grade classroom and identify the sidelined students, likely to leave school earlier than others, without much difficulty.

But, something seems amiss here. If teachers are eventually evaluated on average class grades, what is it that incentivises parents and teachers to behave in this way towards their own wards and students? Do India’s education policies end up encouraging learning traps instead of dissolving them? Can overworked parents and teachers really shoulder the blame? (P.S.: The answers can be found in part two of this series. Stay tuned!)

Click here to read more about life inside India’s classrooms and schools, curated by The Bastion and Teach For India’s teaching staff, under “Jolly Good Fellows”.

Featured image courtesy of Upasna Sachdeva. | *Names have been changed to maintain anonymity.

[…] This article is the second instalment of a two-part series on why learning traps ensnare children in cycles of poor academic performances, and what can be done to dissolve them. Click here to read part one. […]

[…] You May Also Like: Trapped! What’s Putting a Glass Ceiling on Students in India’s Classrooms? […]

[…] You May Also Like: Trapped! What’s Putting a Glass Ceiling on Students in India’s Classrooms? […]

[…] Trapped! What’s Putting a Glass Ceiling on Students in India’s Classrooms? by Upasna Sachdeva […]

[…] This is article is the second instalment of a two-part series on why learning traps ensnare children in cycles of poor academic performances, and what can be done to dissolve them. Click here to read part one. […]

[…] You May Also Like: Trapped! What’s Putting a Glass Ceiling on Students in India’s Classrooms? […]

[…] You May Also Like: Trapped! What’s Putting a Glass Ceiling on Students in India’s Classrooms? […]