In October 2021, the Supreme Court mandated the compulsory e-filing of cases and petitions by the government for all matters after 1 January of 2022. These efforts, including some other categories that are to furnish e-filings after January 2021 were part of a critical drive to digitalize India’s sprawling judicial system: one that has 4.5 crore pending cases placed before it. A digital judiciary, which includes paperless courts and e-filing services, among other e-services, gives a litigant the option to file their case from any part of the country in just a few clicks, at a time and date of their choice. This brings economy, accessibility, and transparency into the purview of a judicial system. In the age of the climate crisis, this also saves millions of sheets of paper per day, while cumbersome in-person fee collection processes can also be simplified.

The Indian judiciary has only just arrived on the digitalization scene, a transition facilitated by the physical distancing measures implemented during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. With the switch to online hearings, end-to-end digitalization is in place in some of India’s virtual courts.

Documents are filed electronically, arguments are heard over video conferencing/teleconferencing platforms, evidence is submitted digitally, and judges decide cases online either presiding from the physical courtroom or in another place.

By the last quarter of 2020, the Supreme Court and almost all the High Courts were operating in virtual mode. Advocates were filing their pleadings via email at the Higher Courts and attending the hearings via audio-video platforms from their offices. In 2021, High Courts started hearing even regular matters online and the speed of case disposal was picking up. The number of cases heard per day via virtual mode had reached equivalent to the number of cases being heard in a pre-COVID era. District and High Courts virtually heard nearly 1.26 crore cases during the COVID-19 period, while 96,000 cases were heard by the Supreme Court of India.

Due to the enormous number of intricacies involved in hearing cases, the online delivery of court services is not as straightforward as setting up a family video call. Enhancing the quality of courtroom technology and digital literacy is a prerequisite for virtualizing the Courts.

How the Government Has Approached the Digitalizing the Judiciary

“We have seen various examples in the recent past that even after the High Court grants bail, the accused is released from custody only the next day. This is because the bail order is physically transported and received by the jail authorities. Such processes consume a lot of time and are unjust to the accused. So, the digitalization and electronic transmission of orders will support the cause of justice,” says Balraj Kulkarni, an advocate and criminal law expert.

Many countries are already well ahead when it comes to digitalizing their judiciaries. Singapore introduced an Electronic Filing system ‘EFS’ way back in 1997. Several countries such as Brazil, the USA, France, and Canada have already developed and implemented economical, paperless, environment and user-friendly processes which are functional, fast, and successful. “We have been successfully using the e-filing system and virtual courts for the past 10 years or more. It saves travelling time, costs, and offers a lot of flexibility,” says Denise Carmo, a lawyer from Brazil. In contrast, the United Kingdom launched its Digital Case System only in 2018.

In India, the Supreme Court’s E-Committee was established in 2004, after which efforts to enable Information and Communication Technology (ICT) for the judicial system began via the ambitious project of e-Courts. Since then, its scope has transformed.

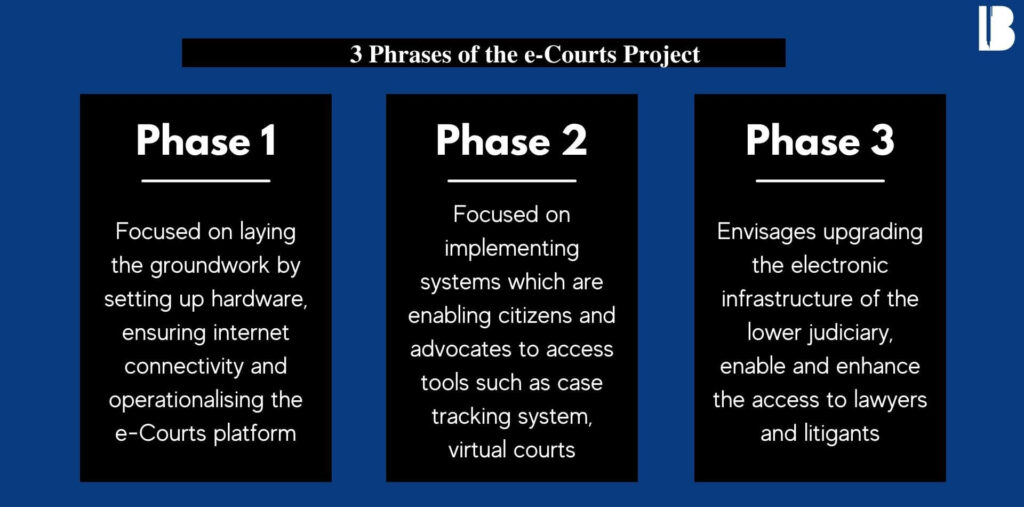

Phase I of the E-Committee’s work focused on laying the groundwork by setting up hardware, ensuring internet connectivity, and operationalizing the e-Courts platform. Phase II focused on implementing systems that enable citizens and Advocates to access case tracking systems, virtual courts, and the e-Courts App. The Phase III draft document envisages upgrading the electronic infrastructure of the lower judiciary, enabling and enhancing access to digital courts for both lawyers and litigants.

Phase III also emphasizes developing the ecosystem for digital justice delivery, by marrying it with sustainable, scalable, equitable and user-friendly methodology. This means transforming procedures to make them suitable for a digital environment—and not the mere digitization of paper-based processes. The aim is to reach a stage where lawyers and litigants can effectively plead their cases either through virtual or in-person hearings, or through a seamless combination of both. This will also demand the implementation of a new governance framework.

This enhancement of ICT in India’s courts through universal computerization, use of cloud computing, digitization of case records, and enhanced availability of e-Services (such as e-filing, virtual courts, and e-payment gateways) still appear to be works-in-progress. It is not difficult to imagine why this is a herculean task, given that India has around 19,000 courts. “It will help if the virtual courts project is fast-tracked,” says Sneha Desai, an advocate from Pune. “The effective implementation of e-seva kendra at District and High Courts is essential for the success of the ambitious project digitalizing India’s Judiciary.”

The Challenges Digitization Faces

Protecting the right to privacy of legal stakeholders is one of the biggest concerns when considering the data storage of litigants. Data aggregation cannot violate the privacy standards laid out in 2017’s landmark Puttaswamy judgement, especially since India is yet to pass legislation enacting a data protection regime. The digital divide is another concern that can impede the growth of digitisation in the judiciary, wherein a large number of advocates and litigants lack access to the basic infrastructure and high-speed Internet needed for virtual hearings.

There’s also the question of India’s overall lack of digital literacy, because only 38% of households in India are said to be digitally literate. The ambitions of the e-Courts program will not be realized until all stakeholders are adequately educated to make full use of the benefits. A case in point: there is hesitation from judicial staff and advocates to make use of digital services, as they themselves lack the digital literacy or infrastructure needed to do so. Given that the Indian judiciary is currently heavily dependent on human resources, many advocates also fear the creation of disparity between Courts at different levels and loss of monetary and business opportunities if technology takes over most judicial procedures.

What Next?

The rights of litigants and advocates will have to be protected while the tech revolution is ushered into the Indian judiciary. A 360-degree profiling of litigants and other entities as well as storing data in an interactive unified database is a genuine requirement that must be initiated at the earliest. Migrating from maintaining localized data to centralized data will lead to significant improvements in resolving queries and creating an environment for artificial intelligence to be implemented at a broader scale.

Phase III the e-committee also envisages the tech-based exchange of information between the judiciary, the police, and prisons through the Interoperable Criminal Justice System (ICJS). Uniformity and standardization in information management will provide anonymous, aggregated, and statistical information about issues without having to identify individuals.

To address the question of digital literacy, the Department-Related Parliamentary Standing Committee On Personnel, Public Grievances, Law And Justice recommended exploring the feasibility of involving private agencies to take videoconferencing equipment to the doorsteps of people who are not tech-savvy, to help them connect with e-courts. It also recommended that the judiciary consider launching mobile video conferencing facilities in remote areas. Additionally, the Committee recommended introducing computer courses into legal courses so that law students become comfortable beforehand with navigating judicial e-services.

Due to demands from various quarters, the Supreme Court and the High Courts have gone back to offline hearings since October of 2021, a move which has made it difficult for litigants and advocates from far off places to attend higher courts without having to incur time and expenses for travelling. Given the shortcomings described earlier, the hybrid model of offline and online proceedings as envisaged in phase III of the e-Courts project is perhaps the most suitable to the Indian scenario. If implemented at a brisk pace, such concrete steps may help transform the Indian judiciary beyond its current perception of being slow, expensive, and cumbersome to navigate.

Sorry 😞😞 sir i don’t have money for this but your articles helpful for my civil services exam……but one day i will pay for my upcoming fellow ..for free and pure content…..