Written by Suyash Tiwari

The last couple of months have been an uncomfortable period for Indian football. As the I-League clubs struggle to maintain their position as the stalwarts of the game, much has been said about what is going to happen next. While the Asian Football Confederation (AFC) Champions League berth has been given to the Indian Super League (ISL) — this is traditionally given to I-League clubs — the I-League has been left hanging. And this is just one facet of the entire situation; at its centre is a battle for how to design, and who controls the future of Indian football.

The Story thus far

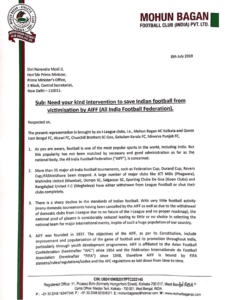

Last month, a 2010 agreement that was signed between the AIFF and IMG-Reliance started making rounds in the public domain. The contents of this agreement added more fuel to the fire, that suggested that the ISL would be made India’s top tier league. That the I-League would be made subservient to its newer counterpart is apparent; just take a look at this letter by Chennai City FC to the AIFF.

Time and again, the AIFF has consistently denied rumours (till early this month) saying that the ISL will become the top league. But this 2010 agreement clearly proves otherwise.

In response to this, on June 24, some I-League clubs — Mohun Bagan, East Bengal, Churchill Brothers, Minerva Punjab FC, Aizawl FC, NEROCA and Gokulam Kerala FC — released a joint statement saying that they will not accept being told that “I-League will no longer be the TOP LEAGUE” and if AIFF took such a decision in their Executive Committee meeting, they are ready to “approach the courts for relief.” According to a letter that these clubs penned, despite repeated requests to meet, the President of the AIFF, Praful Patel had not entertained their requests.

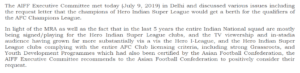

Finally, Patel met with the representatives of the ‘rebel’ clubs on July 3rd to discuss the path ahead. However, the decision (given on 9th July) does not show much consideration toward the I-League. The Executive Committee of the AIFF wrote a letter to the AFC requesting them to give ISL the Champions League spot. AIFF reasoned this decision with the following statement:

This decision implies that the I-League will not retain their spot as the premier football league in the country — only the winners of the top league in the country get a spot in the competition. However, in anticipation of a decision like this, the clubs wrote a letter to PM Narendra Modi on 8th July regarding their reservations.

As Things Stand

The I-League owners are in dismay, feeling abandoned in this decision about the future of the sport. Ranjit Bajaj, the owner of Minerva Punjab, has been vocal about the entire issue on social media. Speaking to The Bastion, he says

“they took away our Champions League spot and according to FIFA articles, the top league of the country’s winner gets the spot. So, officially or unofficially, they [ISL] became the top league of the country. And we are the ones who have, for the last 25 years, played and earned these two spots for the nation. ISL has not earned these two spots, we have. So, they just coming and taking it away and then saying that you have no right of getting it is wrong”.

The AIFF had initially proposed a merger of the two leagues. While this seems to be the only way out, a sudden merger will come with its own problems. For instance, I-Leagues would refrain from paying the entrance fee and would face difficulties to match the investments required in ISL. If the I-League clubs are exempted from the entrance fee, then obviously, it is not fair for the ISL clubs that have put in money to be a part of the league.

To counter this, the proposed merger described a three-tier league system, with the ISL and some I-League clubs in the top division and the other I-League clubs in the second-tier and third-tiers. But the issue here was that there would be no relegation from and promotion to the first tier! This means that the second tier would have relegation but not promotion, while the third tier, comprised of the second division teams, would have both promotion and relegation.

This format discourages new clubs to invest more in their players and organisation as regardless of the promotion, the new clubs cannot play in the first division.

“I said that if you put Minerva in the third division also, I’m happy as long as there is promotion and relegation. You can’t say that Minerva will be in the second division, but you will never get to the first division, even if you win the second division. But if you come last, you’ll be relegated. This is the first league in the world where there is relegation but no promotion and that is what they were proposing to do with our league.” says an aghast Bajaj.

Of Business and Tradition

Honouring the 2010 ‘Master Rights Agreement’ would see the AIFF fill Rs 700 crore into its coffers. There is little doubt that making the ISL the premier league will boost revenues for AIFF. But where should the line between business and development/sporting merit be drawn?

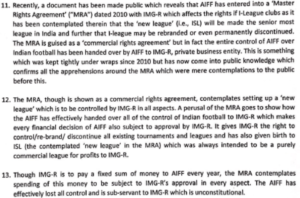

The 2010 agreement gives more power to IMG-Reliance than is preferable, essentially diluting the powers of the AIFF as well (as can be seen from the points laid out above).

“…our fight is not against the ISL. In fact, I actually support some of the ISL clubs, I love them. We need people like that, who put so much money into the game. Our fight is for survival; we don’t want to die because of commercialisation. We want a situation where it’s a win-win for everyone. Here, it’s only a win-win for Reliance. Because the only one who is making money right now is Reliance; whether it is the Star Sports revenue of 450 crores or the 165 crores from franchises. So, they are making 650 crores 700 crores a year, whereas every ISL club and I-League club is losing money. I want a situation in which the clubs make the money!”, exclaims Bajaj.

There is also the much spoken about the aspect of footballing culture and tradition here. The I-League has a culture that has developed over the years and embedded itself into the heart of the football system in India; aspiring footballers look up to the I-League to improve and someday, join the league as a stepping stone for better things. Even though the monetary benefits are not as good, new teams have joined and sponsorship has increased by 22%. From 2014-2019, six new football clubs have participated in the league. Three of these have won the league and have sent players to the Indian national team. The viewership shall also increase if the league is promoted diligently, like ISL.

“… you have to actually spend time and grow with the fans. If a fan has grown up with the club, it’s a different kind of a feeling. But if a fan comes to this club formed two days ago and it just might shut down the next day, it’s very difficult for the fans to give all towards that team. So, I think you always require big teams, but you require small teams as well. One cannot have 20 Manchester uniteds or Arsenals playing, you have to have the Leicester Citys and Southamptons in there as well. If you have only 10 big clubs with a lot of money, then you are basically saying that sporting merit is dead. But sports is all about sporting merit, isn’t it? Why do people love football? Because any small team can beat the big team and in fact, the I-league has proven this time and again.” says Bajaj.

Despite several attempts to reach out to the AIFF and get their side of the story, The Bastion did not get any response.

Where do We go From Here?

In 2018, FIFA and AFC produced a joint report that studied the Indian ecosystem and suggested ways to restructure the same. An alternative it suggests is that within the unified league system, there should be promotion from the second to the first tier on merit, while relegation for ISL clubs would be enforced only after original ISL contracts run out. Addressing the financial issues that might arise out of it — the ISL earns a decent chunk of its revenues through franchise fees (between Rs. 10-15 crores) — the report suggests that the I-League can pay smaller franchise fees, and in return, they get a smaller share of the central sponsorship pool.

This seems like an agreeable middle path for everybody involved; competition for the AFC League spots would be open to clubs from both sides, while the costs and revenues would be borne equitably. In fact, earlier this week, FIFA wrote to AIFF asking for updates on the process and acknowledging that they had been made aware of the I-League’s issues.

Indian football is just beginning to realize its much spoken about promised potential. That all stakeholders involved need to come together to solve this mess is common knowledge; it is the isolating actions of the federation that is surprising. Endangering the world’s most popular sport which is finally beginning to grow on the larger Indian sporting consciousness is not only shortsighted but is disappointing. FIFA and AFC’s joint report, as mentioned above, must be taken seriously into consideration as a recourse before things get really ugly. Not much can be said about what’s next, and all the 125 million Indian football fans can do is sit tight and hope for the best.