Photographed by Sumit Mahar

Suleman is a stressed man. In May 2019, the Shimla High Court had passed a seemingly positive order, considering the relocation of his house and 32-member joint family from their current residence in Kenduwal, a village in the Baddi area of Himachal Pradesh’s Solan district. Yet, almost a year later, his family is still where they were. “As per the latest court order we went and met the District Collector in January, and he assured us that the new land will be handed over to us by early March,” says Suleman. “But the date of the next hearing has moved ahead, and with it, so has any final decision on our relocation.”

The continued stay in their home had become so unbearable, that in 2018, Suleman along with 1200 other residents living closeby had written to authorities-including the President of India-to grant them permission for voluntary euthanasia, rather than to continue living in Kenduwal’s toxic atmosphere.

The ‘toxic atmosphere’ is due to the unscientific dumping of industrial, bio-medical, and municipal waste near Suleman’s house. For the past five years, this waste has been collected from the Baddi-Barotiwala-Nalagarh Industrial area. While Solan district has almost 6000 small, medium and large scale industries operating as of 2015, in the Baddi-Barotiwala region alone, over 1400 industrial units are estimated to be open for business.

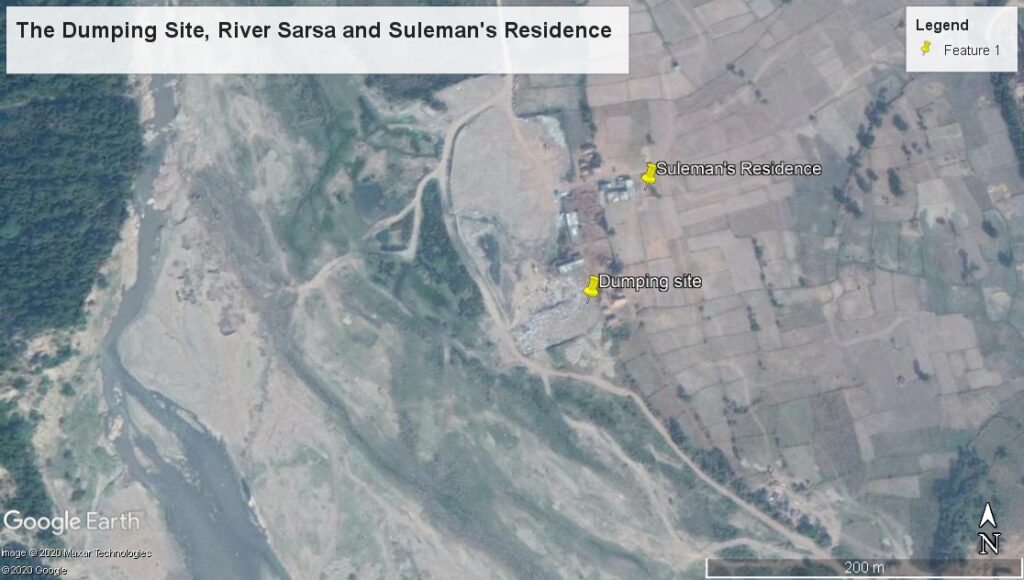

These industries, along with Municipal Councils of Baddi and Nalagarh and 41 Gram Panchayats dump their untreated waste in the dumping site in Kenduwal. Suleman’s family is the most directly impacted by this waste dumping; their home is barely 30 metres from the dumping site.

But here is the biggest irony—what is now a site of unscientific dumping of untreated waste was supposed to be an Integrated Solid Waste Treatment Plant. It gained its environment clearance in 2015 not just for a landfill, but also as a site for the segregation of municipal solid waste, composting, and a sanitary landfill. The proposed cost was a whopping ₹970 crore.

Welcoming Industries in Himachal Pradesh

This aggressive push for industries in Himachal Pradesh has been due to state-level industrial incentives notified between 1980 and 2004. The latest feathers in this industrial cap have been the notification of the Himachal Pradesh Industrial Investment Policy, 2019, and Rules Regarding Grant of Incentives, Concessions and Facilities for Investment Promotion in Himachal Pradesh 2019. The latter provides a number of incentives and concessions for industries to set up base here.

The beauty of this area situated at the foothills of the Shivaliks is marred by the landscape that meets the eye here: Baddi is dotted with factories producing textiles, pulp and paper, soap and detergents, electroplating, and food and beverages for well-known brands ranging from Colgate Palmolive, to Hevels India, to TVS Motors, to Ambuja Cement amongst others.

For scientific disposing of the waste, Baddi Barotiwala Nalagarh Development Authority (BBNDA) had been given 25 acres of land in Suleman’s village Kenduwal. The construction of this facility has only just started, but the dumping has been a part of the routine disposal practice here since 2015. As of 2018, a staggering 500 million tonnes had already been dumped here.

There is more trouble in this industrial paradise. Members of Himdhara Environment Collective, a watchdog group that works on environmental issues, analysed data collected from the Pollution Control Board through file inspections and RTI replies. This data showed that more than 50% of the 2063 units were operating without valid consent. Further, they found that in the rare case that show cause notices are issued to units, there is virtually no follow up in the matter by the Board. Additionally, 60% of the units do not have an Effluent Treatment Plant (ETP) in the area, in the absence of which, the groundwater is severely polluted.

In the Lap of Industrial Pollution

“The dumping site is literally in our aangan (backyard),” says Suleman. “So, our families are now suffering from the same foul smell, allergies, and diseases due to the site.” Suleman’s family belongs to the Gujjar community, whose main occupation is rearing cows and buffaloes for milk production and other products. As construction for the Treatment Plant started, the local administration demolished the family’s cowshed, which housed about 30 cows.

Moreover, for most of the 25 years that Suleman’s family lived here, the now dumping yard had been a pastureland for the cattle. “[Now] Our cattle sometimes end up consuming the plastic waste that gets dumped in the site and happens to consume the contaminated water which has deteriorated their health and even led to [the] death of a few in the recent years,” states Suleman in a memorandum submitted to the District Collector in June 2019. Because of the unchecked industrial waste disposal, their major source of income is under threat.

Now, since the dumping, one has to walk through the dumping ground to reach Suleman’s home, since it blocks the only path that leads there. With that, their home and the dumping site have become synonymous.

Apart from cattle rearing, Suleman’s family also engages in a bit of agriculture. For irrigation, they depend upon their tubewell. “But if the dumping continues, our groundwater too will get polluted,” Suleman explains. “Just look at Sarsa right now,”

Polluted Water

Sarsa is the perennial river on the banks of which this Treatment Plant lies. When the Central Pollution Control Board assessed 351 river stretches in 2018, of which seven were in Himachal Pradesh, they found that a stretch of this Sarsa was the most polluted river stretch in the state. This stretch of Sarsa lies between Nalagarh and Solan, which, unsurprisingly is also the industrial stretch.

Suleman’s groundwater prediction is not too far in the future. A 2011 study by Panjab University assessed the groundwater of the Baddi-Barotiwala Industrial belt, revealing that levels of iron, lead, copper, manganese, and alkalinity had crossed desirable limits, and in some cases, even permissible limits. It even indicated towards possibilities of major diseases like haemochromatosis, severe inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract, and liver damage, for those who consume the groundwater.

It is not surprising then, that between 2013 to 2018, over 2000 cases of gastroenteritis, more than 15,000 cases of renal infections, around 7000 cases of diarrhea, and 190 cases of cancer were registered from the catchment area of Sarsa river, as a report by Himachal Pradesh Pollution Control Board shows.

Now, to ensure that only treated industrial waste entered the river, a Common Effluent Treatment Plant (CETP) just ahead of the Solid Waste Treatment plant was also given clearance. But, in 2019, the National Green Tribunal found the CETP had been discharging untreated effluents into the Sarsa. It then slapped a fine of ₹1 crore on the CETP.

“The fact that this plant is on a floodplain is in itself a large problem,” Sumit Mahar from Himdhara says. In fact, this had not gone unnoticed by the Expert Appraisal Committee (EAC), the union body that advises the government on environmental clearances of development projects.

The EAC deferred the project twice-in 2012 and 2013. The rejections were made on various grounds, including the fact that “the existing site is very much in proximity of the river. Site is not suitable for setting up an MSW facility” and thus, an “alternate site should be selected.” But, in 2015, the project received approval, subject to a series of conditions.

A series of non-compliances

Not only has this dumping been against the Solid Waste Management Rules, 2016, it has also gravely non-complied with the conditions put forth by the MoEFCC.

This was uncovered during a routine monitoring visit by Dr. Bhawna Singh in 2017 who visited the site to check the status of compliance of the plant. She reported that of the 36 specific conditions to be complied with by the MoEFCC, the project did not comply with even one. All conditions have been marked by either ‘not complied’, ‘project not yet constructed,’ or ‘No information provided’.

Of the other 22 general conditions, only one has been complied with. “No significant construction work was found yet undertaken, however the project site was found being used as a landfill without obtaining Consent to Establish and without adequate protection measures,” the report states. It even asked the project authorities to “suspend any landfilling activity until ‘Consent to Establish’ from the State Pollution Control Board was obtained.”

Further, the Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) of the Treatment Plant also suffers from a glaring loophole: it mentioned that the nearest habitation was “4-5 km from the site and 500 metres” from the site. “In doing this, the EIA completely invisiblised Suleman’s family, who live barely 30 metres from the site,” mentions Sumit. “Since their residence was not documented, the EIA did not mention any scope of their resettlement or rehabilitation.”

Implications for the State

Suleman filed complaints with the MoEFCC, BBNDA, and the Sub Divisional Magistrate (SDM), Nalagarh. No action followed, despite the SDM charging the Municipal Council of Baddi with Public Nuisance in 2018. Then, Suleman proceeded to file the case with the High Court of Himachal Pradesh.

“One of the better things that happened during fighting this case was that it has become much larger than what it started off with,” comments Deven Khanna, the advocate who has been fighting this case pro-bono. Khanna is referring to the December 2019 order of the High Court based on this case, which directed the Secretary of Urban Development, Himachal Pradesh Government, and DCs of all districts to file a status report on solid waste management.

What began with a small village in Solan now had implications for waste management in the entire state. “We have received the affidavits from almost all bodies now, and are beginning to assess them,” Khanna continues.

The case of Baddi’s Treatment Plant is not just a story of the environmental and social impact of industrialisation in Himachal Pradesh, but also that of non-compliances and illegalities. While Suleman’s family might be the most directly impacted, the impact on the environment around due to this dumping has been immense. As far as Suleman’s relocation is concerned, the process of looking for alternate land for relocation of all 32 family members has begun, but is yet to be completed.

“We still do not know how much longer we will have to live here,” Suleman sighs.

Sumit Mahar is an independent photographer and works with Himdhara Environment Research and Action Collective, Palampur, Himachal Pradesh.

[…] of the Himalayan state. Ground reports from Kullu-Manali, Shimla, the industrial hub of Baddi, and the Smart City of Dharamshala all report the similar trend of unscientific and unsegregated […]