A new B-school graduate finds himself on his first day at work as an analyst in an investment bank. He is facing a spreadsheet with 45 tabs and a 200-page annual report - a smorgasbord of information on the company. Yet, he sits there, paralyzed by this tsunami of data. He aced all his financial risk management exams, but today he doesn’t know how to start and use all the information together to make recommendations.

Another young man has just taken over his father’s vegetable farms. His father has been using the traditional method of farming so far, but he is interested in marketing his produce to the organic restaurants mushrooming at some distance from his village. Should he start switching to new methods in a staggered manner or change everything in one go? Should he bring in experts? A bunch of other farmers are switching as well, how can he market his produce best?

As illustrated in the examples above, real life has a knack for presenting problems, not in neat siloed bite-sized pieces, but as complex problems with incomplete information, mixed-up subject areas, and no single solutions. Unfortunately, our education systems still focus on drill-and-kill memorisation and repeated-application-to-antediluvian-situations approaches. These fail to prepare us for the tide ahead, which include life-and-death situations as the current pandemic shows us.

Enter, Project Based Learning

Project based Learning (PBL) is an instructional methodology that looks to mirror real life. It does so by providing students with an engaging real-life problem or question which they work on over an extended period of time. PBL uses an inquiry-based approach where students ask questions, seek information, and finally design and present solutions. In the process of these projects, they gain knowledge as well as skills like problem-solving, collaboration, creative and critical thinking, and communication. Finally, as these are extended projects, students get plenty of opportunities to receive feedback and revise their answers, reducing the stress that a conventional single-right-answer exam brings.

But wait a minute, aren’t many schools prescribing “projects�? already?

Well, not exactly. Schools that have partially embraced this approach, especially in India, currently focus on PBL in the form of “dessert�? projects or performance tasks. These are assigned at the end of the semester where students are assessed on a project they’ve worked on for a few days. These projects are typically “illustrations�? or models of something learned.

PBL, on the contrary, is a “main course�? approach. In PBL the projects are the main tool used for teaching curriculum and not only for assessment. PBL is central to the curriculum, not peripheral.

A key differentiator of PBL v/s performance tasks is the role of investigation. PBL requires students to inquire, seek knowledge, and interpret. If the project can be carried out with pre-existing knowledge then it is more of an exercise and doesn’t qualify as PBL. It is this investigative element of education that we overlook the most, yet it is the most useful in real life – as the cases above elucidate.

Is PBL Worth It?

As knowledge becomes more and more democratic (anyone can know anything at the click of a button!), it loses its value, making our current ways of teaching obsolete and defunct. The skills employees and entrepreneurs of tomorrow need are the ability to research and analyse data to make and present a decision.

These are the very aspects that a PBL curriculum covers. Even if it does so at the cost of providing less formal content knowledge, it’s definitely worth it. Where’s the smoking gun? Well, the field is replete with research at levels from primary to high school to even universities. Most research concludes an increase in student engagement and a much higher depth of learning when a full PBL or combined PBL approach is used in classrooms. Blumenfield and Krajcik even conclude that PBL leads to higher scores on standardized tests than traditional learning.

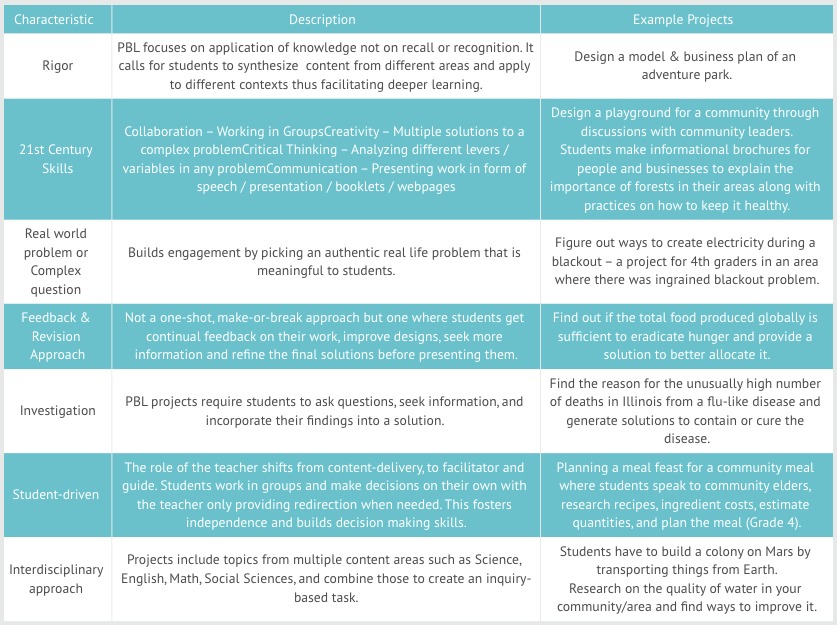

Yet, as one can imagine, running a PBL curriculum is not an easy task. As seen in the table below, it requires a lot of meta-thinking and rigor to design meaningful projects that map and integrate several content topics into a single driving question or challenge.

There are organisations such as PBL Works run by the Buck Institute for Education, and Expeditionary Learning Education in the US, who have pioneered the design of these projects, while also providing partnerships that include content and curriculum support, and teacher training and assessment rubrics. They also have Open Source libraries of such projects that can be accessed by anyone. Several organizations such as ASCD and Defined Learning have libraries of cross-curricular projects that schools can subscribe to and access. However, most of these organisations are based in the US and hence the standards of curriculum have to be contextualised better for different countries’ needs, especially India’s.

What PBL Can Do for India: Developing Meaningful Skills and Bridging Learning Gaps

As of now, we run the majority of our schools for the top 20-30% of students who ace exams and follow the content taught at school and/or have the wherewithal to pursue higher education and utilise their knowledge in professional courses (as evidenced in Gross Enrolment Rates in Higher Education of ~25%). This is especially true for low income private and government schools which constitute more than 75% of our schools. The rest of the students lose out on the way to becoming a working adult, often failing to even see the use of school knowledge in their professional lives.

Incorporating skills like decision-making and problem solving along with exposure to a multitude of real life problems can make education egalitarian and relevant for all Indian children (In the same way “Google�? makes information egalitarian!), whether they enter the workforce as plumbers, engineers, small-time entrepreneurs or homemakers. It has the potential to build a constant improvement mindset that is much needed in our country’s education system. Perhaps there is no better time to realize this now, in these unprecedented times as millions of us face extraordinary challenges and difficult choices to make – from our hypothetical B-school graduate to social workers to small business owners.

You May Also Like: Trapped! What’s Putting a Glass Ceiling on Students in India’s Classrooms?

Then, there’s the question of how PBL can help bridge social gaps present in our education system. Year after year, the Annual Status of Education Reports (ASER) point to our students’ learning gaps, lacunae in basic literacy and numeracy skills, and abilities to apply content. If the same old strategies aren’t working, can an out-of-the-box approach like PBL help? It looks like the answer is yes!

Research by Horan and Lavaroni (1996) showed that while PBL enabled a significant improvement in critical thinking and social participation for high ability students, the gains in the same parameters for low ability students were even higher. A multi-year study by the University of Michigan in high-poverty communities showed that PBL led to improved outcomes in reading, writing, and content knowledge, reducing the gaps between them and higher-income schools.

Despite these benefits, PBL hasn’t been taken up widely in India because of two reasons. One, after covering the breadth of syllabus, schools often don’t have sufficient residual time for live projects and two, and especially important for our rural and underprivileged schools - PBL being an investigative student-driven model does mandate some access to technology in the form of laptops/phones and internet - penetration of which is poor and sketchy still.

Learning & Growing Organically

After visiting and researching several progressive schools across the country, and the world, we chose to go with Project Based Learning as it led to extraordinary student and teacher engagement. Through the process of solving a real-world problem, every child acquired in-depth knowledge and life-skills, as well as learns to become a good human being. — Bhavesh Gandhi, Founder, The Polymath School, Mumbai

There is hope though. Over the last few years, a few mid-to-high income progressive schools have sprouted across India which have taken a full PBL leap. These include Heritage Xperiential Learning School in Gurugram, the Charter School in Thiruvananthapuram, and the budding The Polymath School in Mumbai.

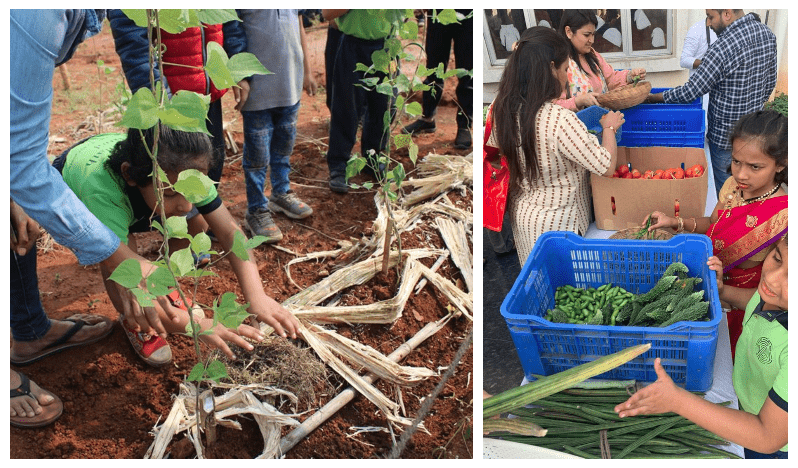

The Polymath School which started a few years back ran a year-long project on organic farming as one of its first projects. Students of different grades created a microcosm of a village by running their own farms at the school campus, and growing vegetables, flowers, and fruits like gourds, mahua, pumpkin, mango, aloe vera, and orchids among several others. These students under the guidance of organic farming experts learnt how to grow food organically, take care of farms sustainably, track growth, and make organic manure. At the end of the year, they held a Farmer’s Market where they sold their own produce to various organic consumers and organic-based restaurants!

Through the course of this project they learnt the basics of botanical science concepts such as pollination, balance of nature, food cycles, symbiosis, nutrition and soil, weather patterns, and basic mathematics. They also gained exposure to the basics of economics, through pricing and marketing. In addition, the project also helped students develop an appreciation for farmers and their role in the socioeconomic structure of the country, as well as the problems ailing agriculture in India today.

By structuring learning experiences in the local environment of students, PBL promotes an understanding of the immediate environment holistically from all perspectives rather than in a theoretical vacuum. This builds sensitivity and awareness that most of us as products of a mechanical system lack: an awareness that would have probably led to averting this crisis we are in today. Not only that, but by focusing on “doing�? and getting hands dirty, it builds an appreciation of all jobs and their interdependencies in the fabric of an economy – something the current migrant crisis should have forced all of us to think about, in these days of isolation.

A Constantly Improving Society

The teacher is not in the school to impose certain ideas or to form certain habits in the child, but is there as a member of the community to select the influences which shall affect the child and to assist him in properly responding to these influences (..) I believe that the only true educations comes through the stimulation of the child’s powers by the demands of the social situations in which he finds himself.

John Dewey, one of the most famous education reformers of the 20th Century said this in 1897. Unfortunately, we still do more of the former than the latter.

A constantly improving society is one where education builds a lifelong thinking ability and the desire to improve one’s own life as well as others. These are habits, and habits need to be inculcated. To do this we need two crucial components: A social system that promotes the dignity of labor of any form, and an education system that serves the needs of all by mirroring real life, through skill-based knowledge and building mindsets. While we work on the first part, perhaps PBL can provide a fillip in the right direction for the second.

To conclude, here’s a capstone example of PBL-the Teach for India Fellowship-a two-year fellowship focusing on building leaders for Education in India. In it, fellows are trained for two months and then assigned to their project government or low-income schools with the challenge of closing academic gaps, inculcating values and a growth mindset, and exposing the students to more. These fellows learn and train as they go along and receive continuous feedback on their work. Over this two year experience, the fellows develop an awareness of education in India, enhance problem-solving abilities, and develop leadership skills for them to use as they tackle the problem of educational inequity in India. And as anyone would vouch for, over the ten years of Teach for India – the model works!

Featured photograph courtesy of The Polymath School, Mumbai