Written by Vaishnavi Rathore

The curvy highway that cuts through Himachal Pradesh’s Mandi district remains a busy one, with HRTC buses passing frequently. During the months of March and April, the sides of the road remain busy too, as a few sellers sit with baskets of bright red rhododendron, a flower found in the Himalayan region, which is used to make pickles, jams, juices and chutney.

Further into a village in Mandi, a young boy listens to a track on YouTube, while ushering his cows to the common pastures, glancing at the golden wheat fields, which will be ready to be cultivated in a couple of weeks. With 47% of forest land in the district, even as modernity intersects everyday life, communities depend upon these forests for their livelihoods. But, registers of most of the Forest Rights Committees (FRCs) in the district blatantly, in a few lines announce, “In this revenue village, no one has a right on the forests.”

Questionable Implementation

Nil’ or ‘Zero’ certificates at Panchayat and revenue village levels indicate that Nil claims were made under the Forest Rights Act, (FRA) 2006 almost all across Mandi. FRA, which aims to protect the interests of communities dependent on forest land for bonafide livelihoods and provide legal recognition to forests, is a lost opportunity here. But how was this possible?

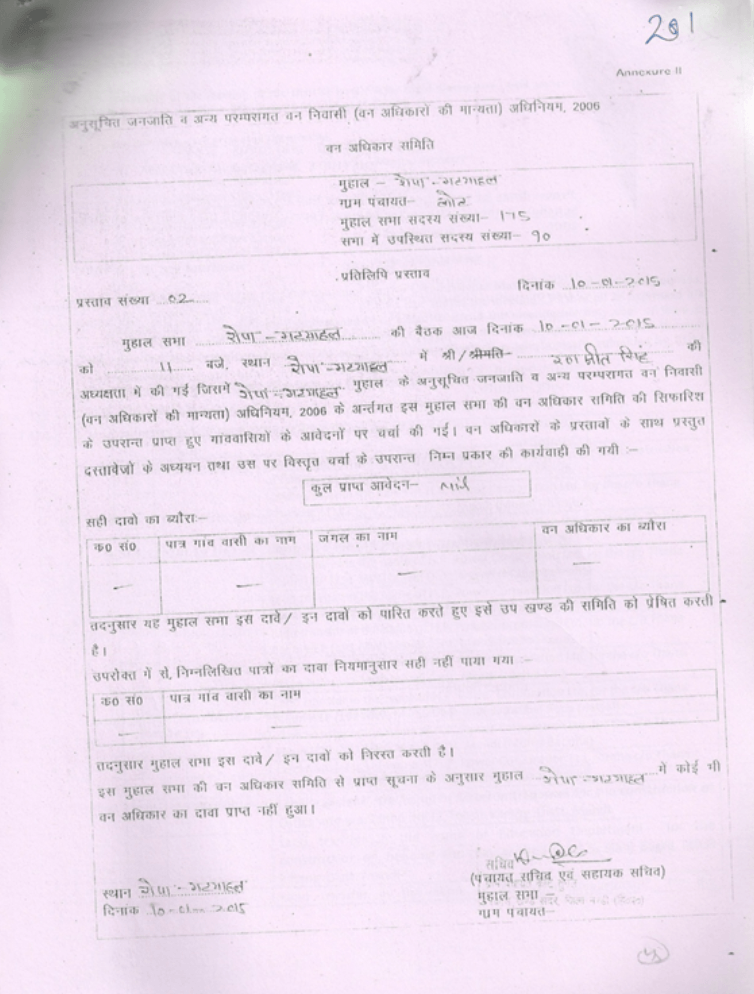

One of the initial steps to claim both individual and community rights as per the provisions of the Act is to invite claims from the communities post the formation of the FRCs. All such proceedings are to be duly recorded in a register, with at least 50% signatures proving a quorum. Following this, files need to prepared, where claimants fill forms, which are supposed to be provided by the government, and attach any two pieces of evidence from the list provided in the Act, to prove their dependency. In Mandi’s case, however, Nil certificates appear as a resolution in the FRC registers (figure 1) and then manifest into filling a form (figure 2). This step is not only absent in the Act, but was also carried out without any representative being aware of the Act itself. With this, the rights of lakhs of probable claimants remain compromised.

Prioritising ‘Development’?

“You step out of your house, and forests begin there. How can the Panchayat Secretaries sign that there is no one dependent on the forests?” asked Rita* from the Khalanoo Panchayat. With Mandi being the second most populous district in the state, Rita is only one of the many residing here who depend upon the forests for fodder, fruits and flowers, firewood, and water springs. With the rivers Uhl and Beas flowing through the district as well, such a bounty of natural resources makes Mandi not only a boon for its residents but also a district with lucrative resources to tap.

An airport is proposed in the Balh valley of Mandi, while three cascading hydro-electric projects have been proposed on the Beas; Thana Plaun, Dhaulasidh and Triveni Mahadev of which the 191 MW Thana Plaun Project is to be in Mandi. The infatuation with quickening the development of these proposed projects then, is not surprising.

“We have literally cut and presented our arms to the government, with such a statement,” says Daleep Singh, Secretary of a Kisan Sabha made specifically for families affected by the Thana Plaun Project. “Our rights have been snatched from right under our noses.”

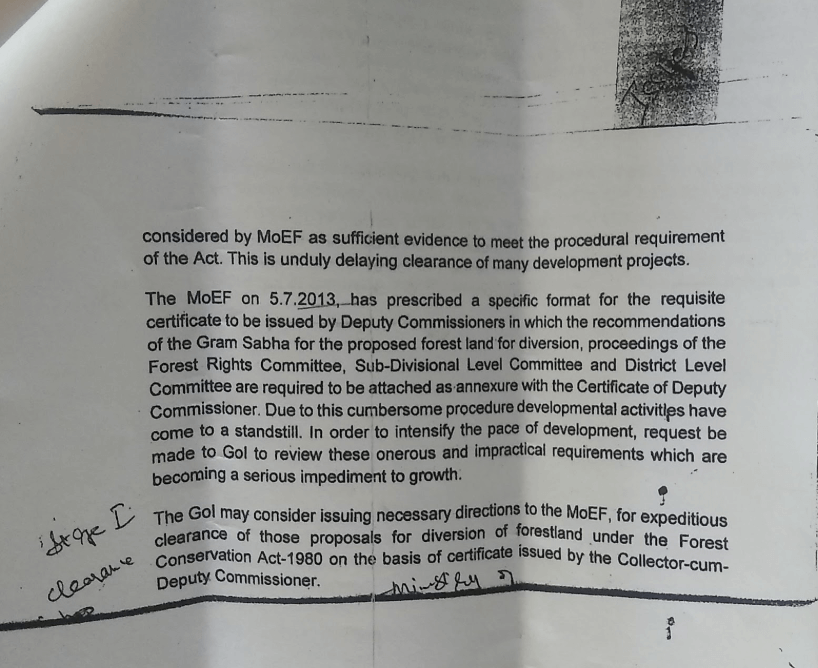

In the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Energy (Hydropower) 2018-19, the Himachal Government’s representative reiterated the need to fast track Hydropower projects, citing FRA as a “problem”, and “diluting” this would be necessary to fast track the projects. In fact, a letter by the state government which mentioned the process of settling rights under FRA, requests the Government of India to “review these onerous and impractical requirements which are becoming a serious impediment to growth.”

It was the same need of quickening clearance processes that saw FRA as an obstacle to development, with which the blanket ‘Nil’ certificates found their way to the DC’s table through a process that was not only unlawful, but also sidetracked all democratic processes.

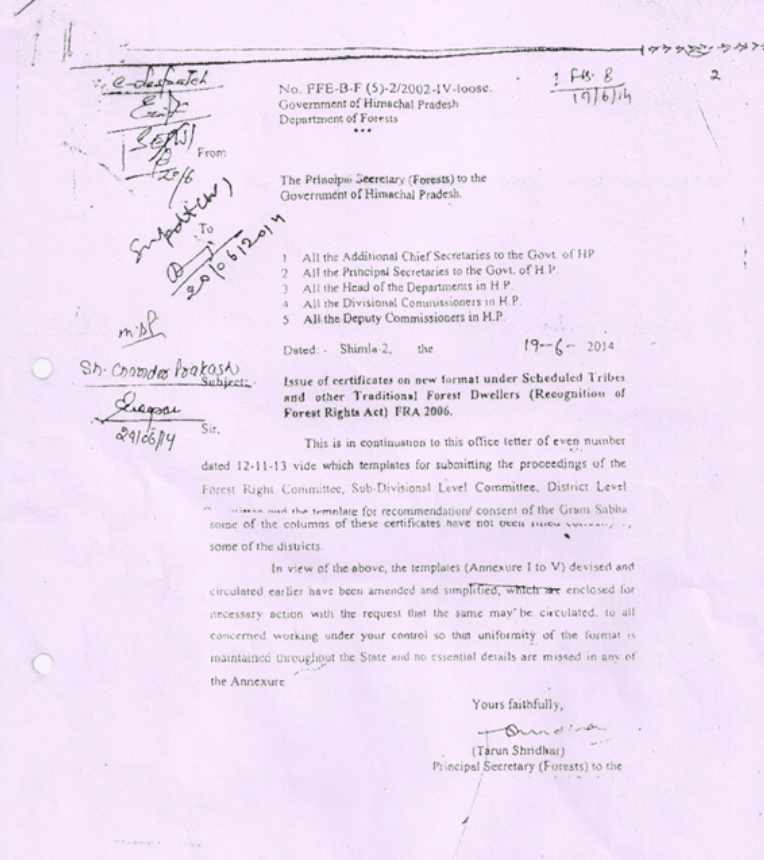

These certificates seemed to be issued on the instructions and through a format issued by Principal Secretary (Forests) in June 2014. “The Authority to issue instructions is with Ministry of Tribal Affairs, while at the State level, the nodal agency is the Tribal Department,” quotes a memorandum submitted by Himachal Van Adhiar Manch (HVAM) — a platform for activists and community organisations in the state — to the district administration in April this year. “We object to these Nil certificates since the forest department has no authority to issue any guidelines or prescribe formats for implementation of FRA, 2006,” it reads.

“In the name of ‘training’ of FRA,” mentions a Panchayat Secretary, “all Panchayat Secretaries were called by the then District Collector and were told that the Act provides for rights to develop 13 types of facilities like roads and anganwadis. Nothing was mentioned about the Individual or Community Rights that could be vested.” With a mostly defunct District Level Committee (DLC) and no training for Sub Divisional Level Committees (SDLCs) or FRCs, Panchayat secretaries and residents gave up rights under FRA.

Further, this process was carried out in clear violation of a 2009 MoEF&CC advisory; this required “a letter from each of the concerned Gram Sabhas, indicating that all formalities/processes under FRA have been carried out and that they have given their consent to the proposed diversion and the compensatory and ameliorative measures, if any, having understood the purpose and details of proposed diversion”(emphasis added). Contrary to this, the Nil claims given in Mandi are blanket claims that do not mention a particular project or diversion in particular, and are also used as a No-Objection Certificate (NOC) for projects.

Protecting the FRA, Protecting the People

“What has happened in Mandi is an injustice to its 1.5 Lakh families,” says Shyam Singh Chauhan, a member of Zilla Parishad and District Level Committee (DLC). “We require these forests as much as our ancestors have required them.”

The Nils have become a dangerous weapon in the war of clearances, where these general Nil certificates can be used for any upcoming project without keeping the communities in the loop; Moreover, it conceives the threat of restricting the access of primary users of forest and those dependent upon it.

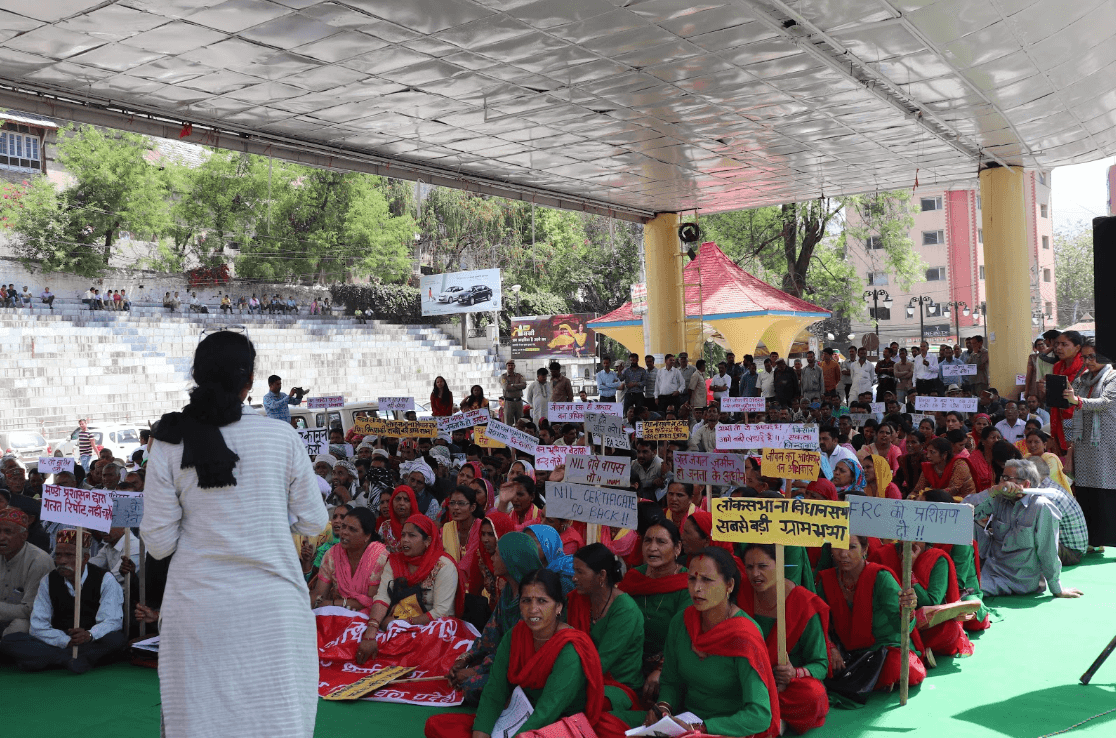

In a meeting held by the State Level Monitoring Committee (SLMC) last month, a decision regarding the issue of Nil certificates was passed; “these templates (referring to the 2014 format) are not to be used for settlement of forest rights under the Act.” The discussion at the SLMC was a result of a public meeting held at the district headquarters of Mandi by HVAM, specifically upon the issue of Nil certificates, where close to 600 people of impacted villages attended.

While this decision may prevent further Nil certificates in the rest of the state, it does not acknowledge that Nil claims have already been issued by almost all the FRCs in Mandi. Until they are taken back by the administration, the process of verifying rights under FRA cannot be initiated.

In the Lok Sabha session on 18th July, Union Transport Minister Nitin Gadkari said, “a poor country must decide how far it can go in spending public money to protect the environment and balance out development needs.” The FRA, which could have taken care of both, protecting the environment, while catering for developmental needs that the local community desires, still remains in the shadows. And all this while, the forest rights of people in Mandi, continue to hang precariously by a thread.

Featured image courtesy Yogesh Upadhyay