Dr Arunabha Ghosh (AG), founder-CEO of the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW), is a prominent figure in the energy and environment development fields. A founding board member of the Clean Energy Access Network (CLEAN), he was nominated by the UN Secretary-General to the UN’s Committee for Development Policy in 2018. In the same year, the Government of India appointed him as a member of the Environment Pollution (Prevention & Control) Authority for the National Capital Region. Today, in a conversation with The Bastion’s Sourya Reddy (SR) Dr Ghosh talks about India’s energy challenge; from energy security to the Indian state’s focus on sustainable development, he sheds light on where we are today, and what needs to be done for a more secure future.

Sourya Reddy [SR]: India’s dependence on oil imports has continuously increased over the past few years. How do you think this affects our energy efficiency goals?

Arunabha Ghosh [AG]: I would put it in two ways. The first is that import dependence in itself is not a problem; most economies around the world, whether rich or poor, are import-dependent. In fact, it is a bit of tilting against the windmills to try and be completely independent. Energy security is not the same as energy independence. So, my second point is that we are thinking of imports and the oil bill in the context of energy security. If we had sufficient money, there would be no problem; we could keep paying for our imports. The point is that we do not have sufficient money.

Now, any disruption in our oil supplies has a macro-economic impact at home. So energy security for India has to be about access to energy resources when required, at a price that is both affordable and predictable, with minimum risk of supply disruption, and keeping the sustainability of the environment in mind. If you accept this as the definition of energy security for India, the question of oil imports rising must be looked at using this definition.

So first, is the change in oil prices predictable? No; oil prices have seen continuous fluctuations, thus making it hard to budget correctly. Are the supply disruptions possible? Yes; the most recent instance is U.S. sanctions on Iran, from whom we import a lot. Thus, does importing assure a supply whenever we need? Not always. And finally, is it environmentally sustainable? No.

Therefore, we have to think of alternate fuels not because of imports, but because it makes sense that we tap into the energy resources available at home, with choices which we can use for a much longer period. So it is in this regard that we need to measure whether our rising oil imports are making us more energy-secure or not, and to that extent, they are clearly not helping. Can we stop oil imports overnight? Of course, we cannot. Can we begin to taper the curve down? Yes. We can become more energy efficient and thereby reduce the total demand for oil itself. Thereby, do we open up new markets for energy-efficient technology? Yes.

SR: The potential of renewable energy has been continuously spoken of, especially in the context of energy-generation. How is it possible for India to create and ensure equitable access to this potential energy, especially in rural areas?

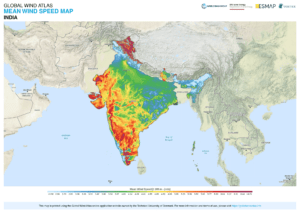

AG: The potential for renewable energy in the current scenario for India is significant. We are already one of the largest renewable energy markets in the world but unfortunately, are nowhere near achieving the full potential that we have. Our current goal of 100,000 megawatts (MW) of solar energy by 2022 should be a floor and not a ceiling. We can get to 200, 300 or even 400 gigawatts (GW) of solar energy given the amount of light we receive. Similarly, we can go well beyond 60 GW of wind energy, to reach several hundred GWs.

So, this raises two questions. One, can the energy system absorb this and two, who would use it? For the energy system to absorb intermittent renewables, we need a better upgraded and smarter grid that will be able to balance the intermittencies, the solar power that is generated when the sun shines, the power that is generated when the wind blows and more. Given that there are variations on a daily and seasonal basis, it has to be complemented with other energy sources while having good storage capacity.

Here is where we can look at the second approach for answers — distributed energy. The more you have a distributed energy infrastructure, the more you empower the consumer to become both the producer and consumer of distributed energy, and the less you need to depend on grid stability. This is precisely where rural areas offer a market opportunity.

Currently, the grid has been extended to all villages and to most households, but this does not guarantee that electricity is flowing through it, because power utilities are not in the best health. Therefore, the role of distributed renewables in providing energy access, not just for households but for community energy and for productive energy, is immense. Now, what do I mean by community energy? Community infrastructure, whether it is a school or a primary health centre or a post office, can use distributed renewables to power itself and deliver better-quality services. As we found in a poor state like Chhattisgarh, nearly 900 primary health centres in villages are solarized, which improved health outcomes and the footfall in these centres.

There is an income-generating side here as well; once you begin to use distributed renewables for the rural economy, whether it is the agricultural sector or the non-farm sector, you find that there is more than a $50 billion market opportunity. So the point is not so much about whether we need to ensure equitable access; the point is that once we recognize this huge market opportunity, and once we recognize the community and social benefits of distributed renewables, there is automatically a business case for renewables to spread in rural areas.

SR: Can increasing our focus on building up the renewable energy segment help create new kinds of jobs in the economy? If so, in terms of scale could you describe how effective this kind of job-creation would be?

AG: Let’s start with the basic numbers. Our (CEEW) estimation is that if we get to 100 GW of solar energy and 60 GW of wind energy, we will create 1.3 million full-time equivalent jobs. This translates to a workforce of about 330,000 people because the same person can be employed in different projects throughout the year. This is by no means a trivial number; Coal India Ltd., for instance, employs 350,000 people.

More importantly, beyond the macro number, is the type of jobs being created. The more we focus on distributed renewables, the more jobs per unit of power can be generated than utility-scale renewables; seven times more jobs from rooftop solar than utility-scale solar, more jobs from utility-scale solar than from wind, more jobs from wind than from natural gas, and more jobs from natural gas than from coal-based power generation. So an improved job story is a significant co-benefit of a clean-energy transition.

We’re releasing a report w/ @GERMIRnD @IWMI_ on our analysis of benefits of solar irrigation pumps which found that installation of solar water pumps could help India surpass its solar target of 100 GW by 2022. Read the report here: https://t.co/Q9pQ9iBnnQ #SolarPower #GoSolar pic.twitter.com/4RhVP5WT7e

— Greenpeace India (@greenpeaceindia) July 31, 2018

At the same time, this will also require skilling. Many of these jobs are neither highly skilled nor completely unskilled; they are somewhere in the middle and will require the use of skilling-centres near the areas where these projects are going to come up. This will help employ local labour. This is not going to be the way jobs were created under thermal power, for instance, where jobs were created near the coal-mine or a thermal power station, and electricity is shipped all the way across; the more you have distributed energy infrastructure, the more you are able to distribute the job-creation as well.

In general, a more sustainable development approach creates entirely new jobs. Whether it is how we manage our water systems urban or agricultural irrigation systems; whether it is how we manage waste and circular economy around waste; whether it is water discharge, electronic waste or mineral waste, we are actually creating new jobs where none existed before, as opposed to greening the workforce.

SR: Do you believe that the Indian state over the years and with different governments in power, has understood and been committed to the concept of sustainable development?

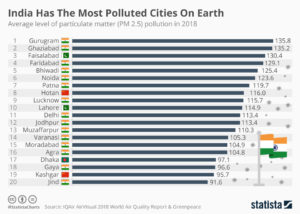

AG: In general, no. As a government and as a society, we have tended to believe that sustainability and development are antithetical to each other, that there is a necessary cost of development and that we can think about sustainability once we have developed. This made sense when we were a poorer economy. But as we are nearing a three trillion-dollar economy, we are struggling to breathe in our cities. This is not just an environmental impact but also a severe public health impact; air quality is one of the biggest killers in India now, more so than diarrhoea or tuberculosis or malaria. And this affects other things as well; foreign investment might not be coming in because people do not want to invest in a country which has poor sustainability standards. We might not be attracting the best brains, because they do not want to come and live in our cities. In that regard, sustainability and development are not antithetical; in fact, one drives the other.

This has not been entirely internalized. Different governments have focused on different things; some might have focused a lot on water recharge, some on afforestation and others on renewable energy. However, the Indian polity as a whole has not yet understood that sustainability can be a driver for not just a new kind of development, but can also result in a faster rate of development. Once this happens, there will be a whole new economy opening up; new industries and new jobs will enhance our ability to compete with nations like China. These are countries that are betting on the new industries of sustainability, and we need to make such big bets.

SR: If you were put in the driving seat to chart India’s future for the energy sector, how would you go about doing it?

AG: Number one, I would start with pricing energy and the resources that go into energy; The market price of energy has to paid by everyone. Only then can we have support for those who are struggling to pay. It is because the market price is distorted that leakages and corruption exist in the system and that the investment that goes in into building more efficient energy infrastructure also gets reduced.

Number two, I would focus on a clean-energy transition, whereby we see that a shift from solid to liquid fuels and to electricity, actually enables us to increase the amount of cleaner fuels in our energy mix.

Number three, I would go beyond the electricity sector and focus on the industrial sector. There is a huge untapped opportunity to use clean energy sources for both, industrial energy efficiency and to create entirely new industrial value additions. This would make the industrial sector a major driver of value creation.

Number four, I would focus on an integrated energy approach and combine distributed generation and consumption of energy with sustainable mobility and the delivery of energy services in commercial establishments. Once we start looking at that, we can create a more integrated and empowered energy infrastructure, as opposed to the current system in which citizens are passive receivers of near-efficient energy services. I believe these would make a good foundation for the next steps.

Views expressed are personal.