The global fashion industry employs over 60 million workers and generates $2.5 trillion in revenue worldwide every year. Its contribution to environmental degradation is just as widespread. When thinking about pollution, images of overflowing landfills, oil spills or vehicular emissions may come to mind. Subsequently, in discussions about climate change, clothes and their major role in pollution are often forgotten.

From Catwalk to Clothes Rack

Brands that rely on mass manufacturing are known to use ‘planned obsolescence’ as a business strategy. When manufacturers sell products that aren’t durable, consumers will need to continuously purchase similar products in order to maintain their lifestyle. This translates into increased profits for the producers. For example, Apple ensures that your iPhones slow down when a new model is introduced. Fashion brands do this as well — your clothing is designed to wear (pun intended).

Yet again witnessing first hand the massive amounts of clothing and textile waste filling landfills around the world. pic.twitter.com/dw5caymBox

— True Cost Movie (@truecostmovie) July 26, 2014

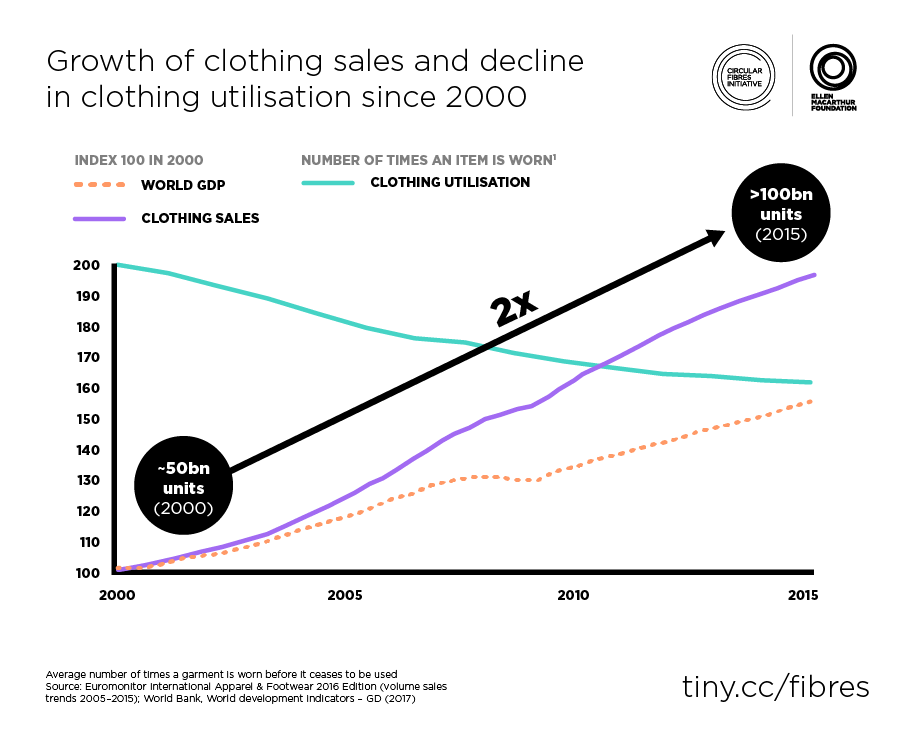

Clothing trends change by the season. Despite trying to keep up, we often find ourselves with a seemingly outdated wardrobe. Designers are kept bust on a “creative treadmill” to ensure that customers are forced to keep coming back for more. Thus, the fashion industry has systematically normalised the idea of disposability. Consumers have lowered their expectations and are prepared to do away with items after just a few months. In addition, they are also prepared to let go of pieces just because they are no longer in style, regardless of wear-and-tear.

With a constant demand for more clothing, suppliers increase production by accelerating manufacturing processes. “Even if we walked into H&M and all the polyester t-shirts were replaced with organic cotton garments, we would still be using so much of cotton which we don’t actually need,” says sustainable textiles designer Neha Rao in an interview with The Bastion.

Dirty Fashion

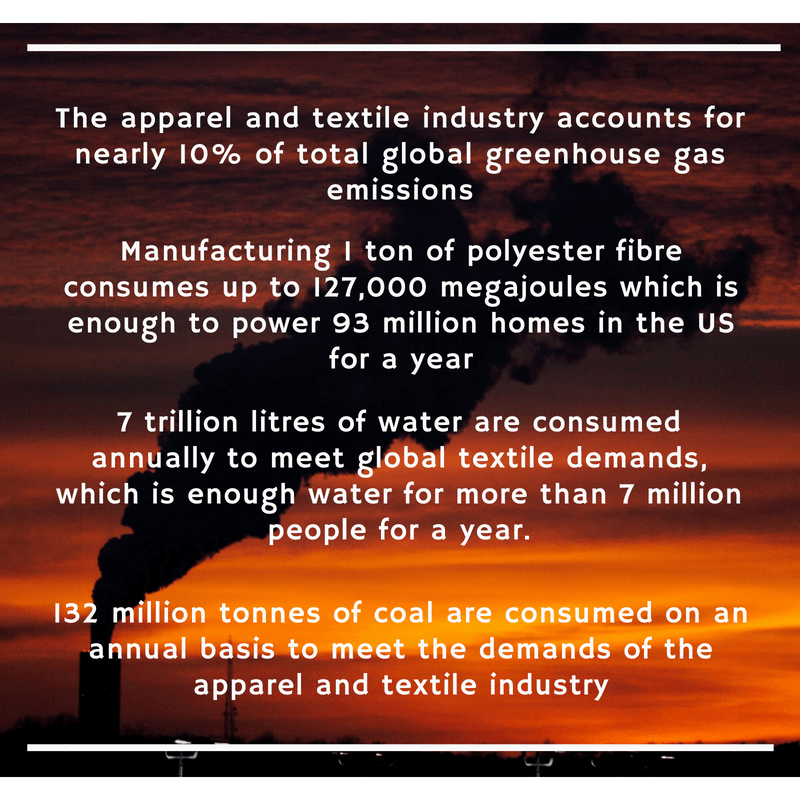

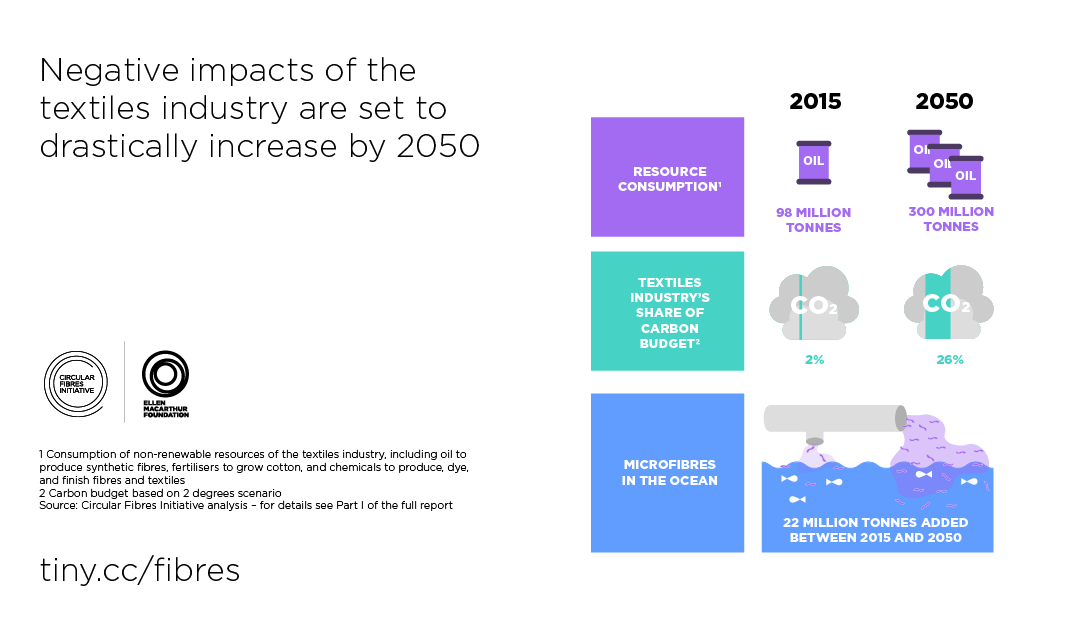

Like most industrial manufacturing, clothes manufacturers focus on extracting the most work from the cheapest resources available, instead of prioritising long-term sustainability. Consequently, increased production leads to increased pollution. This ‘catwalk to clothes-rack’ craze increases the profits of producers at a heavy cost — environmental degradation. While big fashion corporations reap the fruits, our entire planet bears the brunt of fast fashion.

Owing to the limited availability of cotton and other natural fibres, fast fashion has catalysed synthetic textiles’ takeover of the garment industry. On the one hand, organic materials like cotton require huge amounts of water during the manufacturing process; so, less water-intensive synthetic fibres may seem like an ideal replacement. But, on the other hand, producing the chemicals that make up synthetic fibres releases more pollutants than the processing of organic materials. Irrespective of their composition, the bulk manufacturing of textiles puts enormous pressure on environmental resources in one way or another.

Taking it Slow

The ‘Sustainable Fashion’ movement emerged in the public domain towards the end of the 20th century. It followed the rise of “conscious consumerism”, which is broadly a phenomenon wherein consumers make informed decisions about their purchases by keeping environmental pressures and ethical considerations in mind. The ‘Slow Fashion’ trend came through this movement — it advocated for environmentally conscientious manufacturing processes and the production of more durable textiles.

Recently, a ‘Circular Model of Production’ has been conceptualised for the fashion industry. This involves shifting manufacturing processes to:

- make all raw materials recyclable, or at least reusable;

- encourage shared access or ownership of the products, for example, through platforms which allow you to rent clothing, like Flyrobe;

- recover used materials from consumers and reuse/recycle them so as to minimise raw materials’ utilization.

Such a model is cost effective and would allow brands to access new markets. Further, it would eliminate the production of unnecessary waste and prevent resource exhaustion, thereby creating a healthier environment to wear your clothes in.

The movement to make fashion sustainable has found a home in India as well. In early 2018, six North-East Indian designers presented their slow fashion products at the Lakme Fashion Week. They showcased garments made with natural fabrics that created little waste during production, thanks to indigenous weaving techniques. Weavers from Anakaputhur in Chennai have launched their own organic jeans — pants that look just like denim but are, in fact, made from organic banana fibre fabric.

The Problem with ‘Sustainability’

Consumers may not be able to tell whether a garment was produced conscientiously simply by looking at it. This is where ‘eco-labelling’ enables consumers to be informed about the said garment’s lifecycle thus far. The Bureau of Indian Standards introduced ‘Ecomark’, a sustainability certification for textiles. Yet, it has not gained popularity. Customers still have to do their own research regarding popular brands’ manufacturing practices; few will have the inclination to do so consistently. Unless more popular fashion brands participate in making information more accessible to consumers, eco-labelling will remain inaccessible and conscious consumerism will remain a burden for customers.

One of the reasons why sustainable manufacturing is not popular is because it is relatively more expensive to produce. “Today, when someone can get a t-shirt for ₹300 from H&M, why would they want to spend more on something sustainable?” laments Tanushri Shukla, the founder of Chindi. “This is where you have to consider the unethical and unsustainable practices that these fast fashion brands use to make clothing so affordable.” Fast fashion is preferable because producers would much rather burn through the environment rather than their own pockets via their manufacturing processes. The Rana Plaza collapse in 2013 and the literal cries for help from unpaid Zara workers last year stand testimony to this fact.

NYT fashion critic Vanessa Friedman has a different outlook on the issue. At the Copenhagen Fashion Summit 2014, she drew attention to the fact that the concept of ‘sustainable fashion’ is an oxymoron in the first place. Fashion is inherently dynamic, while sustainability requires stability. She introduces the alternative concept of a ‘sustainable wardrobe’, which places the onus of sustainability on the consumer. It requires consumers to wantonly invest in durable garments which they can maintain for long durations instead of throwing them away after a few uses. Not only will this reduce waste but it also signals to brands that consumers are demanding for producers to manufacture better quality clothing. Hence, a sustainable wardrobe indirectly forces producers to let go of their planned obsolescence strategy.

Today’s use-and-throw culture has not always been around. Our grandmothers passed down durable, quality saris from generation to generation. When we spoke to her, zero-waste blogger Mehndi Shivdasani reaffirmed this notion: “People have been getting clothes stitched cost-effectively for decades in India; it is only now that we’ve been engulfed by this high brand, fast fashion mindset”. Maintaining clothes, mending them and using second-hand garments are some ways in which a sustainable wardrobe can be actualised.

Even so, producers cannot be absolved of all responsibility. The end game is to shift the fashion industry’s focus from monetary profit to ensuring holistic global benefits. The fashion industry must thrive on quality production by using sustainable methods and materials to manufacture affordable fashion. After all, owning a sustainable wardrobe will be easier if the global fashion industry is conscious of its impact on consumers, its employees and our environment on the whole.

Click here to read The Bastion’s interview with Tanushri Shukla, Mehndi Shivdasani and Neha Rao.