Researched by Ishita Lohani

Written by Ayan Tandon

Despite the multitude of failings associated with Donald Trump’s capabilities as POTUS, he possesses a reputable knack for fuelling controversy over issues which would have seemed trivial to most other politicians. One of the more vociferous disputes arose over Trump’s decision to withdraw from the Paris Trade Agreement in June of this year. While most of his detractors roared in abject dismay of such a belligerent act, Trump supporters saw this as a bold move against the tyranny of the supposed ‘myth’ of climate change. But why is an issue wherein individuals are equitably harmed (what with sea levels rising and the ozone layer depleting) creating such polarization amongst the masses? This article finds itself in the divisive space between climate change and public policy; in order to understand the bases for divisions in opinion, we must first resolve ad hominem aspersions both sides tend to fling at each other.

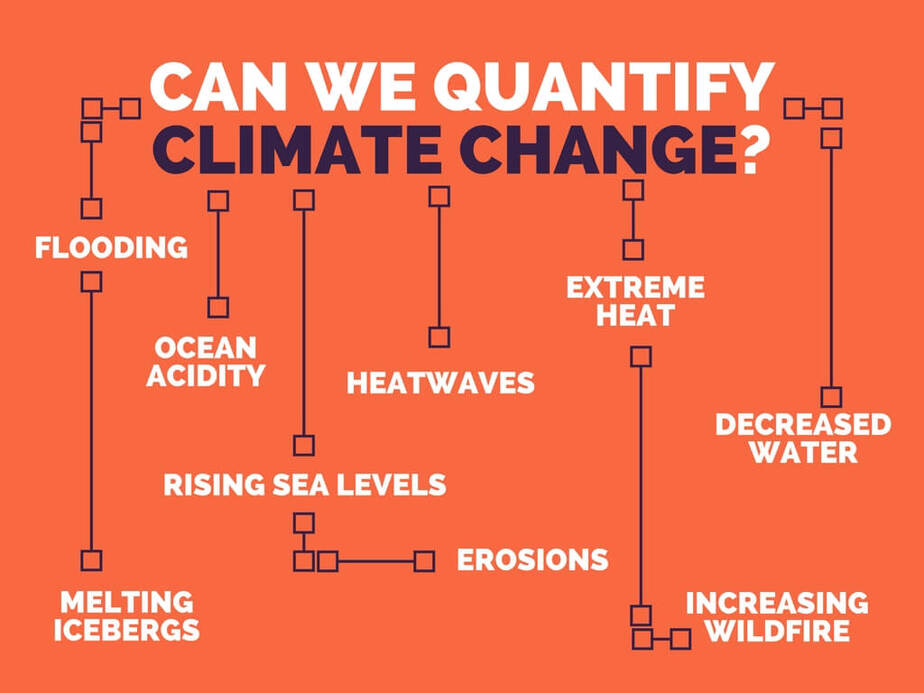

In order to understand the degrees of disagreement, we can compartmentalize the climate change conundrum into three broad questions on the topic: First, is the climate even changing? If so, what is the extent of human contribution to this change? And finally, how severe are the consequences of this climate change? As we probe further, the incongruence in public opinion rises alongside the emotional volatility with which it engages in these conversations.

On the first question of whether the climate is changing, the academic consensus is almost indisputable. Although one may occasionally come across the claim that global warming is a hoax, there is no evidence to contest the rise in temperatures across the world. The various metrics scientists concern themselves with — including Mean Global Temperatures, Global Carbon Emissions and Global Sea Levels — have all been rising steadily over the last several decades. The carbon emissions which were close to 220 parts per million (ppm) during the ice age crossed 400 for the first time in 2013. Over the last century, the planet’s temperature rose over 0.8 degrees. Such data is fairly straightforward to understand, and although such information may be cumbersome to collect, it is unlikely to be incorrect and is definitely indisputable. The avenues for contention, therefore, lie elsewhere.

The answer to why global temperatures are rising depends on two factors: those of man and nature

The drivers of natural warming are the sun’s radiation, volcanic activities and natural emission of sprays; rises due to the burning of coal and petroleum are man-made. Still, the negative impact of human beings on the environment is barely contested when compared to the discontent regarding the extent to which climate change is influenced by human activities.

The causal impact of the man-made rise in global temperature seems to be based off of the unprecedented rate of change. This has been linked to the heightened usage of coal and petroleum products. The rates at which every additional year is experiencing excessive heat is far greater than if the temperature was predicted by models that focus on the natural impacts of climate change. Although scientists do tend to agree that human agency is a factor in these increasing temperatures, there are certain methodological criticisms which they claim exaggerate the results of our involvement. The variation in temperatures in urban areas in comparison to rural areas is one such example wherein temperatures are rising at different rates.

This dichotomy tells us a different story, one where the rise in temperature creates a kind of local warming due to more cars, rapid construction and the presence of more people. The relatively slower temperature change in local areas indicates a more local warming where temperatures rise more dramatically in urban areas as a result of the quality of life. Although there is a large part of the scientific community that believes that human behaviour plays a significant role in climate change, the degree of consensus varies from a range of 52% as published by the American Meteorological Society to 97%[1] by the University of Cleveland.

The greatest cause of strife comes with the third question, simply because the dilemma of how to act today is inextricably linked to what is expected of tomorrow. Although the costs of climate change are collectively shared, efforts to curb this change require structural changes to society which disproportionately harm certain sections of society.

We may know that temperatures are rising, but what are the consequences of this changing climate?

What we know to be true is that ice caps are melting — both the north and south-pole has experienced a deterioration in ice. Greenland lost 150 to 250 cubic kilometres (36-60 cubic miles) of ice per year between 2002 and 2006, while Antarctica lost about 152 cubic kilometres; such developments have caused ocean levels to rise. Consequently, the absorption of excessive heat by water bodies has led to a change in the patterns of currents in different parts of the world. The results of such macro changes will be said to lead to droughts and perhaps precipitate further disasters like cyclones.

What enables the critics of climate change is the fact that the predicted dangers of these climatic disturbances have not always occurred. For instance, the inconsistency in the Arctic, where NASA published a report in 2015 stating that there was a net gain in the Arctic ice-sheets over the last few decades (although the total gain has been in decline lately). The predicted extinction of species like the polar bear in Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth has failed to occur, which adds to detractors’ arsenal. As always, there have been controversies surrounding the severity of the impact of climate change due to the sheer difficulty of measuring causal impacts in subtle weather conditions. Often, methodological flaws such as the use of ill-advised proxies (like pine-cone trees) lead miscalculations on the effects of the rise in temperatures on worsening weather patterns.

The next part of the dilemma arises in reaching a consensus on which steps we need to take when the impact of the climate change is ambiguous. The problem is that coal and petroleum despite its harms have no appropriate immediate substitute that can sustain productivity at the same costs. Thus, the harm to weaker sections of society would be exacerbated by efforts to curb this usage. In addition to this, the technologies like wind and solar may have worked in certain European countries, however, this system is not as sustainable as somewhere like the USA due to certain geographical factors. The Economist recently published studies that showed renewable energy in Germany has not played a sufficient role in curbing the carbon emissions, which on a preliminary glance seem to have risen. The incentive to disrupt the functioning of societies is reduced to the seeming lack of an alternative.

Donald Trump cited the loss of 2.7 million jobs as a reason for withdrawing from the Paris Trade Agreement. Although the broader media cry has opposed this decision, an academic report from M.I.T. is one of the many which have expressed ambivalence to such a decision. The researchers believe that the goal of avoiding a 2-degree rise in global temperature will not be met by such a policy; instead, they predicted a rise of 3 degrees by 2100.

The dangers of not implementing strong policies may be harmful in the long run. The coral reefs (which can recover if warming stays below 1.5 degrees) will certainly perish in the scenario wherein we do not choose to act adequately. If temperatures rise in higher latitudinal areas, certain crops like wheat and soy may fail, leading to a daunting food scarcity amidst growing populations. The increase in dry spells will also accompany a rise in temperatures over the 1.5-degree limit.

Perhaps, policies more stringent than the Paris Trade Agreement need to be drawn up. Alongside the tradeoff between current benefits and future harms comes an important aspect of this debate: in order to avoid severe complications in the future, human beings and citizens may have to undergo inconveniences today. This complicates climate change predictions and policy implications of the same.

Within social science literature, such a dilemma is categorized as a ‘collective action problem’ where individuals choose to collectively gain benefits or forgo collective harms by performing certain actions. And, immediate costs may deter individuals from acting in these collectively beneficial ways. Keeping in mind the significant immediate costs individuals face, some find it imperative for governments across the world to enforce regulations to influence desirable behaviour with respect to warming. But, at the same time, people far removed from the consequences of climate change or those suspicious of scientists’ ability to predict outcomes may not find the need to nudge their position on the issue. All in all, the information gap in our capacity to predict the severity of climate change is at odds with policies which demand change in our immediate surroundings.

[1] Consensus on Climate Change - Cook Et. Al.