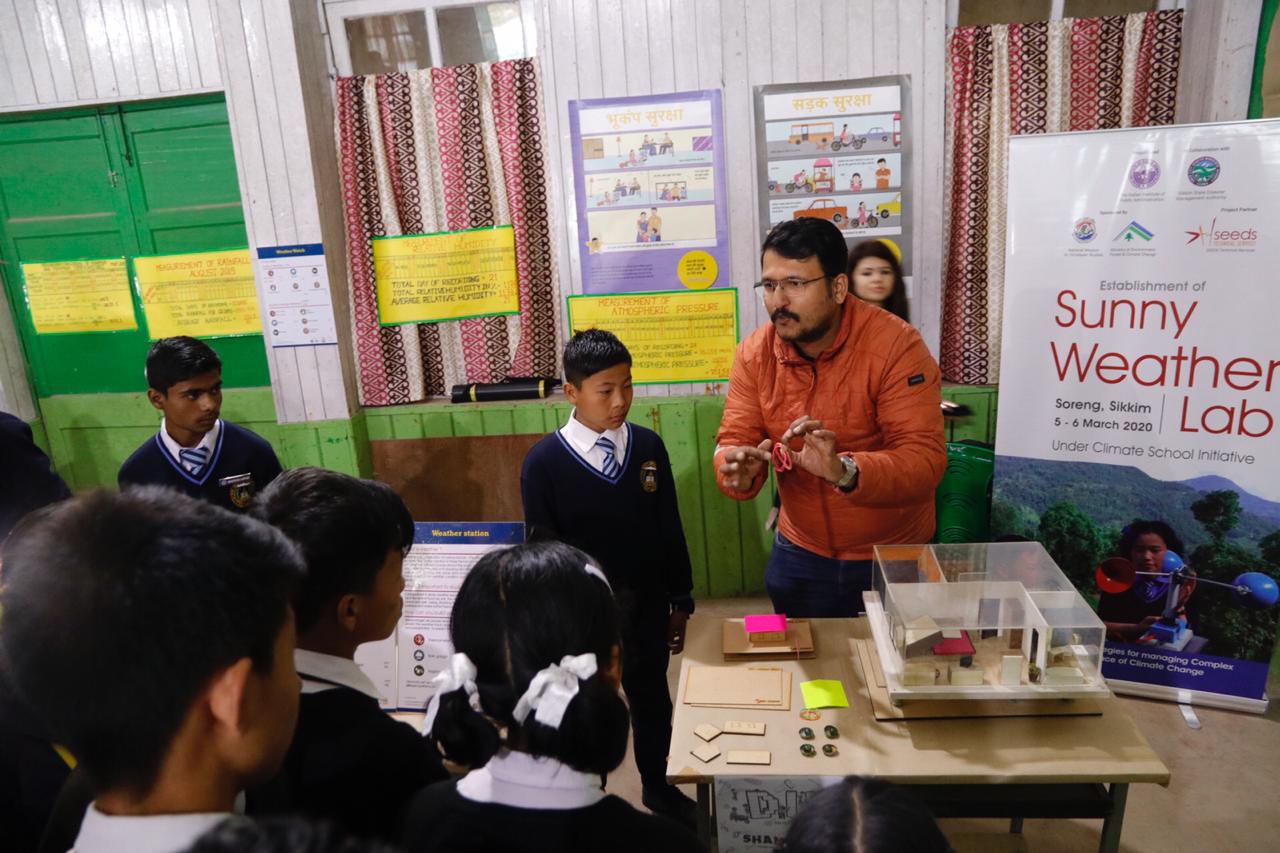

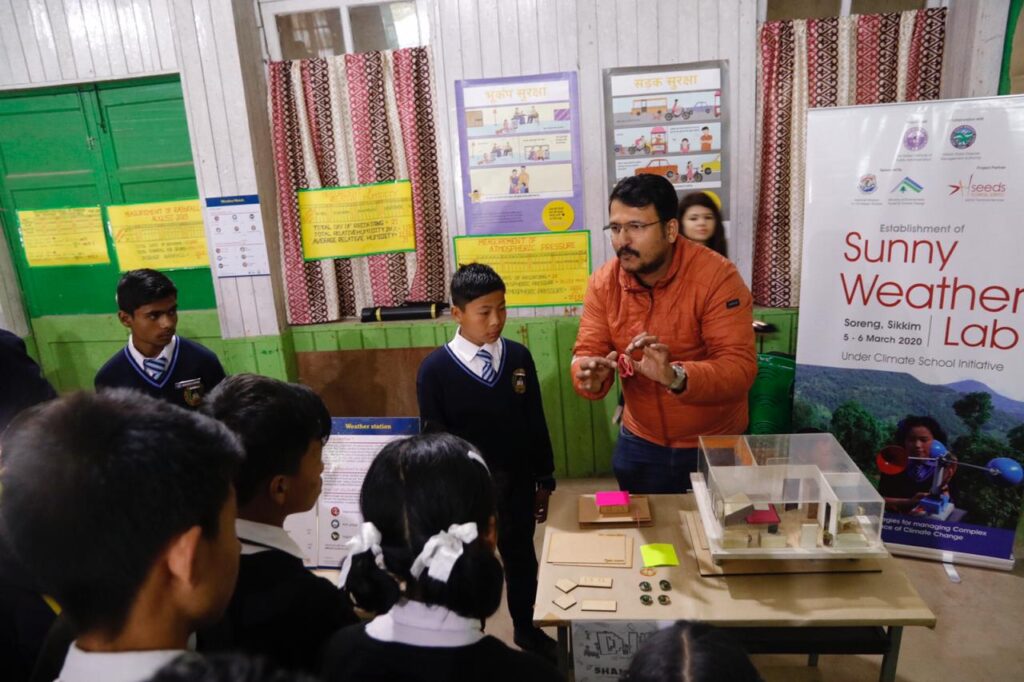

Last week, something interesting was introduced in the state of Sikkim. A ‘Sunny Weather Lab’ to record information like wind speed, temperature, and rainfall was inaugurated by SEEDS, an organisation focusing on creating disaster-resilient and sustainable communities across South Asia. In a place like Sikkim, where the weather differs from one valley to another, depending on the available state-level data does not serve much purpose. So, with the aim of making real-time, everyday weather data available, this project was launched.

But consider this: the daily information is not collected by trained scientists. Launched in a government school, it is instead completely owned and operated by students studying between grades 7 to 9.

Such involvement of the general public for scientific work in collaboration with, or under the direct direction of professional scientists, is a common trend in ecological assessments and termed as ‘citizen science’. While this trend of involving amateurs in natural sciences across the world can be traced back to as far as the 17th century, India is now witnessing a growing interest in citizen science. In 2018, almost one article/news report a week on citizen science was published on prominent English media platforms, as a report co-authored by Pankaj Sekhsaria and Naveen Thayyil shows.

You May Also Like: The Bastion Dialogues: Pankaj Sekhsaria

Democratising Data

Citizen science has opened up the otherwise intimidating world of natural and social sciences to the general public. This allows them to help document large scale datasets, an exercise that requires immense amounts of time and resources. In other words, it has ‘democratised’ data and sciences.

“In the Sunny Weather Lab, students who first undergo training facilitated by SEEDS transfer their knowledge to other students in their school, and even other schools,” explains Dr. Anshu Sharma, the co-founder of SEEDS. The data the students gather will be made available to the local administration, who will then communicate it to the public, signalling a bottom-up approach to data collection and dissemination.

Village Wildlife Volunteers (VWV), a project of TigerWatch India, also shows how a bottom-up approach to data collection can assist in filling in major data gaps for monitoring and vigilance in Rajasthan’s Ranthambore Tiger Reserve. The VWV includes herders, subsistence farmers, and other villagers who give a part-time commitment to the project in the peripheries of the Reserve. “More than 50 % of the Ranthambhore Forest Department’s data on tigers comes from the Village Wildlife Volunteers as they regularly monitor 35 tigers outside the protected areas,” explains Dr. Dharmendra Khandal, a conservation biologist with Tiger Watch.

A similar sense of democratisation is also reflected in a community-based fisheries monitoring system in the Lakshadweep Islands, facilitated by the Dakshin Foundation. The lack of reliable and fine-scale data on the status of the fisheries sowed the seeds for this project. So, for the last five years, a data collection protocol was co-created with the local fishing community to address gaps in the data on their fisheries. The participating boats collect data on a regular basis. The data is then meticulously registered in logbooks during or after fishing trips, which at the end of the season, are collated and analysed for the region by Dakshin Foundation researchers. This, along with the personalised information from each boat, is presented back to the community.

“In this system, those who have a direct stake involved in fisheries are the ones monitoring it,” says Dr. Naveen Namboothri, the Director of Dakshin Foundation.

“After all, data is power, and this system has helped to shift the power from the authorities into the hands of those who are direct stakeholders.”

Is this Information Credible?

Naturally, involving students, or the general public for scientific collection brings in the question of accuracy: how credible will this data be? Citizen science projects have been able to create some accountability mechanisms to check for the same.

For example, eBird, an online platform where users can submit information on birds all over the world, shows us how this can be done: they have appointed region-wise reviewers.

Anil Sarsavan is the appointed reviewer for a region in Gujarat. “All submissions by citizens in this region come to me. I’m very careful when a submission of a rare bird comes my way,” he says. “I ask for evidence, like a photograph from the submitter, so we can verify it before we make the information public.”

Sarsavan works with the Foundation for Ecological Security, which is one of the ten partner organisations involved in publishing a one-of-its-kind report last month “The State of the Birds, 2020.” The report is a comprehensive assessment of distribution range, trends, and the conservation status of 867 bird species, all of which were analysed through the information submitted by 15,000 amateur and professional scientists to eBird.

The State of India’s Birds 2020 report used the observations of more than 15,000 birdwatchers to identify how 867 Indian species are faring.https://t.co/CP4tnI7nVg

— BBC Wildlife (@WildlifeMag) February 26, 2020

Similarly, for Dakshin’s work in Lakshadweep, local residents are appointed as co-ordinators to ensure the credibility of data being submitted. But more importantly, the closeness and affinity of the small fishing community allows for a natural system of self-monitoring. “The credibility of data while important, often takes up the majority of the conversation around citizen science,” comments Namboothri. “But what is as important as data is the strengthening of the relationship that the communities have with their resources and surroundings. By exercising projects of citizen science, this relationship gets accentuated by gathering crucial bits of everyday data, which otherwise would not have been collated.”

Dr. Anshu Sharma believes the same for the students involved in the Sunny Weather Lab. “The students become well-equipped to understand the environment around them, and get the chance to reflect upon it and their relationship with the changing weather. That becomes as important as collecting the data in the first place.”

Who Owns this Data? Who can Use it?

Since most citizen science projects involve data being accumulated in a database, questions like who owns this data? What will be done with it? Who can use it? become inevitable.

A trio of researchers conducted a study amongst 2000 citizen scientists to answer some of these questions. On the question of who owns the submitted records, they found a surprising contradiction: while almost half of the respondents (48%) believed that the data was a public good, only a small 12% of volunteers amongst this half supported the completely unconditional use of data.

The scientists then make a significant observation. They state that while many of the respondents consider data a public property, they might ultimately withhold the data they publish, if they believe that the data may be used for the ‘wrong’ reasons. They term this relationship between the volunteer and nature as an “imagined contract”; a relationship based upon respect as well as an expectation that the “data extracted from nature should properly be used towards its preservation.”

“Our results suggest that [the] violation of this expectation could have grave consequences for both volunteer motivation and their willingness to submit their collected biodiversity data,” the paper concludes.

This calls for providing clarity to citizens about the rules and procedures for sharing data, including whom data may be shared with, when, and why. For instance, eBird mentions on its homepage, “Your sightings contribute to hundreds of conservation decisions and peer-reviewed papers, thousands of student projects, and help inform bird research worldwide.” The Cornell Lab additionally has a detailed ‘informed consent form’, which covers the risks involved and issues of confidentiality.

Only when these facts are set in stone, can we envision the proper use of this data for research, and even impact. For instance, information by VWV provided information for anti-poaching efforts and helped mitigate human-wildlife conflict. Their data has also been used by the Forest Department to pick the correct villages for the relocations of tigers when creating habitats in tiger corridors.

2poachers arrested in joint operation

Based on..tipoff f/village wildlife volunteers of NGO-TigerWatch, officials of.https://t.co/Mpw4CeL0i2 pic.twitter.com/yphmlV0ov9— NoAnimalPoaching! (@NoAnimalPoachin) June 9, 2017

In fact, their data has also been the backbone for groundbreaking research projects by independent researchers. “They [the citizen scientists] discovered a breeding population of the critically endangered crocodilian, the Gharial in the Parvati river, a tributary of the Chambal in 2017,” informs Dr. Khandal. “The Chambal is considered one of the last hopes for the Gharial, so their finding was extremely significant to the scientific community.”

The future of large scale data sets seems to be with citizen science. But, with data comes the responsibility of its right use. In that light, concerns of data privacy and breaches need to be addressed and more comprehensive guidelines for data collection need to be devised, to strengthen this approach for the betterment of the planet’s ecosystems.