Sakshi Lama*, a tea garden worker in West Bengal’s Alipurduar District, is relatively at peace since it is now the peak season for harvesting tea. But she is not without concerns.

Now it is plucking season and things are going fine. We pluck up to 16-22 kg of tea leaves daily and get paid ₹ 202 per day. We work for 6 months in gardens and from September onwards it is the dry season for the next 6 months. We then take up work in the temple or cleaning work for money. Many haven’t yet received the money from the gratuity petitions filed in 2019. Authorities are saying that the process was delayed with COVID.

—Sakshi Lama, Tea Garden Worker, Alipurduar District

For tea garden workers like Sakshi, the tea plantations around her represent precarity; these plantations are their only source of livelihood. The tea industry witnesses fluctuating prices owing to the agricultural nature of its production, which is dependent on unpredictable climatic conditions and long maturation periods of tea plants. Usually, tea plants can take up to three years to mature and produce a good harvest. The deterioration of the industry was further deepened during India’s New Economic Policy announced in 1991 wherein the LPG or the Liberalisation, Privatisation and Globalisation model was adopted. This period saw a decline in the industry as governmental control on market prices decreased and growth in the supply of tea was not complemented by proportional demand.

As a result, several tea estates across North Bengal have been closed down or abandoned since the 2000s, leading to poverty, malnutrition, and even starvation deaths among the labour force who fuel this industry. An increase in abandonment and illegal takeover of tea gardens by private corporations for profitable initiatives such as tourism has also been reported in this region.

A State of Chaos and Confusion: Gardens Closing Down, Being Taken Over

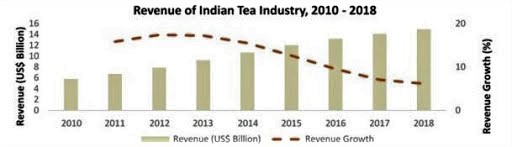

Since India’s Eleventh Five-Year Plan from 2007 to 2012, the export of tea has become stagnant, leading to a surplus of 56 million kg in the market in 2010 alone. The price of tea, a perishable commodity, was determined at a lower price by the free-market mechanisms in the face of a relatively high cost of production. The slump in North East India’s tea industry has also been identified with climatic causes such as floods, droughts, and heavy rainfalls.

Between 2000 to 2004, nearly 118 tea gardens across the 5 major tea-producing Indian states—Assam, West Bengal, Tripura, Kerala and Tamil Nadu—have shut down. 53 of these tea gardens have been shut down in West Bengal alone, most of them in the Dooars region, making it the highest number of shutdowns among any of the other states. This has had some serious consequences on the lives of the people who are dependent on the tea gardens for their food and livelihood. Between 2000 to 2015, 1,400 people died in the tea estates of Darjeeling as a direct result of malnutrition and starvation.

Workers across many estates have been actively protesting against the day-to-day issues they face as garden workers even prior to the start of this year’s season. In June 2021, nearly 1,500 workers from one of India’s oldest tea plantation companies, the Duncans, protested to demand wages as the company battled through insolvency proceedings in the National Company Law Tribunal. In November 2021, the tea garden workers in West Bengal conducted an aggressive protest for two days to demand adherence to minimum wages and other basic facilities in estates.

Unlivable Wages, Unattainable Provident and Gratuity Funds

In recent years, there have been deliberations to formulate the wages of tea garden workers at par with the minimum wages. However, these deliberations have not yielded the desired outcome so far. The tea estate workers’ unions negotiated for wages at a 1:3 ratio, that is, a labourer’s wage is sufficient enough to feed members of their family. But the plantation associations have agreed to only a 1:1.5 ratio stating that, unlike other agricultural industries, the industry employs more than one member of a family.

Adhering to the Minimum Wages Act has been difficult due to the lack of negotiating powers that the workers have, especially for the tribal communities and Nepali immigrants who comprise majority women labourers. Over the years, the formation of workers’ unions and collectives has played an important role in amplifying the precarious conditions of the tea estate workers in this region.

There are separate unions for Nepali workers and those from tribal communities. Even though there are considerable Nepali workers, all the MPs and MLAs from here belong to the Adivasi community and we haven’t been politically represented yet.

—Kuldeep Lama, Coordinator for Madari Block,

Paschim Banga Cha Majoor Samity (PBCMS)

Kuldeep is a native of Nepal and is now based in Alipurduar’s Lankapara Tea Estate where he works as a coordinator of the Madari block of Paschim Banga Cha Majoor Samity (PBCMS), a wing of Paschim Banga Khet Majoor Samity (PBKMS). The PBCMS was formed just 6 months ago specifically for tea estate workers. Kuldeep mentions that the workers Lankapara, his native tea garden, are managing the sales of tea leaves themselves through a workers’ collective. He also emphasises the need for inter-community political representation while discussing workers’ issues.

In 2021, the workers’ wages were increased to ₹202 which is only a ₹26 hike from their previous wages. According to the workers, this amount is payable for plucking a minimum of 16-22 kg of tea leaves a day, and this amount remains the same for women and men workers. The wages marginally increase for plucking tea leaves that weigh more than the 16-22 kg range. Comparing these wages with the existing and proposed hike in wages in India’s southern states such as Tamil Nadu reveals a different reality. In 2021, the wages of Tamil Nadu’s tea plantation workers were revised from ₹345 to ₹425.40, almost double of what the North Bengal workers received.

In March 2018, the Supreme Court of India directed the state governments of West Bengal, Assam, Tamil Nadu and Kerala to make an interim payment of ₹127 crores to tea garden workers who had not been paid for 15 years since the closing down of the tea gardens in respective states. The garden workers are eligible for gratuity and provident funds, which should have been accumulated from their regular wage cut. However, the official filing of forms for such payments is difficult for the workers who are illiterate leading to them not being able to access these funds independently.

Land Rights Issue: Remnants of a Feudal System

The Plantation Labour Act (1951) mandates tea plantation ownership to allot suitable land and housing facilities for tea plantation workers and their families. However, garden workers do not legally own the land or houses they have occupied intergenerationally. The occupation of land and property in plantations depends on whether a member of the household is involved in plantation labour. This system of intergenerational bonded labour in tea gardens dismisses the rights of land to workers who worked in gardens through generations.

Schemes such as the Cha Sundari scheme introduced by the West Bengal government offer “pakka” houses to tea labourers, mostly away from the land they occupied for generations. When asked about the situation of land rights and the proposed scheme, activist and founder of the Paschim Banga Khet Majoor Samity (PBKMS), Anuradha Talwar says, “The situation of workers in all gardens whether closed, illegally taken over or open are the same. No one has the right to the house their family has occupied for 150-200 years.” This is true even of market places and towns like Birpara where the land is still owned by the company and no one can claim any right over it.

Cha Sundari has led to no improvement as far as land rights are concerned. None of the people who shift to these houses are getting land rights. Instead, they are being forcibly shifted to 80 square feet pigeon holes with no trees, no vegetation, and no courtyards, leaving behind spacious green and cool homesteads.

— Anuradha Talwar, Activist and Founder of PBKMS

In 2019, the state government sanctioned 15% land of the tea garden’s to be utilised for alternative purposes. This has resulted in profiteering ventures for tea garden owners who have begun setting up hotels and facilitating tourism instead of utilising the land to create better facilities for workers.

Workers and Tea Industry Impacted by Policy

The Eighth Five-Year Plan from 1992 to 1997 that coincided with the economic reforms phase that followed was also the starting point of the tea industry’s downfall. The industry’s stagnation since the 1990s have not been remedied with favourable export policies or financial support or holistic central and state levels. The plantation industry continues to function as an enclave economy from the colonial era which helps retain high per capita production at low wages. The negotiation of wages in West Bengal and Assam is determined by a collective bargaining system that is unfairly tilted to the whims of employers.

Even for basic basic facilities such as drinking water, healthcare, and sanitation, the workers are accustomed to the facilities available within the tea gardens. Reports from PBKMS indicate that workers mostly handle these issues themselves and rarely approach the union. Given the issues of unpaid labour and question of sustenance within the tea gardens along with a murky state of ownership, these issues remain secondary to workers. There is a need for these issues to be addressed since it concerns the workers’ well being.

Only 15.81% of plantation workers have latrines at their homes and the majority defecate in jungles, a 2021 study from the Dooars suggests. Around 30.7% of households receive drinking water through tube wells leading to high incidence of water-borne disease within tea gardens. The healthcare facilities in closed tea gardens have also deteriorated with the decreasing availability of medicines and ambulance services causing preventable incidents of death.

What Can Be Done at the Policy Level?

There has to be clarity on many levels at the policy side. For instance, with respect to the Cha Sundari scheme, the policy documents are inaccessible for workers to learn more about how the scheme affects them. For underperforming tea gardens, the concerned government departments would know much ahead as to which gardens are getting sick and which are likely to be abandoned by owners.

—Advocate Jayshree Satpute

The tea industry requires financial and structural support for its revival. Policies for reducing excise duties, as done during the Eighth Five-Year Plan, could be introduced to uplift the industry in the medium to long term. Workers’ wages must adhere to the minimum wage rates and be adjusted for inflation while considering their socio-economic conditions as well.

The rampant changes in plantation ownership makes the lives and livelihoods of workers complex. A policy to prevent illegal takeover of garden land is needed. Joint committees with plantation workers, labour unions and plantation owners can be formed to discuss changes in ownership. Land rights research should guide policy-level action in determining alternative land ownership systems, which eliminates the need for intergenerational bonded labour.

Advocate Jayshree Satpute, who is practising at the Supreme Court of India says that legal and policy-level changes for the welfare of tea estate workers are needed. “Many times, the owners flee the gardens without paying workers their dues leaving them even more vulnerable to acute poverty and starvation. In several cases, governments are neither able to hold the defaulting companies accountable in a time-bound manner nor ensure social security for workers. Proactive measures have to be taken to monitor legal compliance in such gardens. The government also needs to ensure that there are hospitals, schools, creches and other essential facilities as mandated by the law in tea estates.”

However, not all tea plantation owners are aloof to the larger status of the tea industry and the crucial role they could play. Take for instance the Darjeeling tea industry that is witnessing a decline over the past decade. The strikes of 2017 and the 2020 COVID pandemic have further intensified the challenges for tea gardens in the region. There are existential problems that tea production is facing owing to the onset of climate change, fluctuating temperature patterns and rainfall. On the supply side, the original structure of selling tea is broken now with the infiltration of Nepali tea, which can be produced at a much lower cost of production and is sold in the pretense of being ‘world-class Darjeeling tea’. Owners are now grappling with these challenges and exploring alternatives.

Also Read: “Slow Onset” Climate Hazards Are Upon Us. How Are We Responding to Them?

Sparsh Agarwal, co-founder of Dorje Teas, a subscription-based D2C [direct-to-consumer or business-to-consumer] company, which started operations in July 2021. With seed funding from venture capitalists and angel investors, Sparsh along with the Selim Hill Collective, friends and veterans from the tea industry want to revive his family’s heritage—the Selim Hill Tea Garden in Darjeeling. The young tea garden owners have a unique vision to modernise the plantation model and also improve the lives of garden workers.

Speaking about the persisting issues within the Darjeeling tea industry, Sparsh says, “The labour management system of the tea industry is outdated. Fair wages are being paid in most Darjeeling tea gardens as the trade union movement here is very strong. However, there are other more deep-rooted issues to be solved.” When Dorje Teas was launched, a worker collective was introduced and mechanisms for waste management, wildlife conservation and carbon credits were set in place. However, financing remains an issue for Dorje Teas since, at present, they are the only ones attempting such welfare measures.

A recent trend that has been observed is the preference for coffee at least among the younger population, and the Darjeeling tea being a luxury commodity, sees no adequate demand as preference shifts. “At the policy level, what is immediately required is to safeguard Darjeeling tea from the mock Nepali tea, and make Darjeeling attractive for climate finance which can help us undertake projects for green growth,” Sparsh suggests.

Even though in the nascent years of its business, initiatives like these offer a ray of hope for the revival of the tea industry in India—an industry that empathises with the garden workers’ well being while creating a sustainable business model. Garden workers like Sakshi Lama deserve the basic rights they are entitled to for sustaining their lives and livelihoods.

Names of tea garden workers have been changed to maintain anonymity. Pictures taken by the author, Ann Mary Biju, are from her field internship with the Paschim Banga Khet Majoor Samity in 2019, where she worked on filing of gratuity petitions for tea workers of Alipurduar District. Featured image is of workers plucking tea leaves in the tea gardens of Dooars in North Bengal; courtesy Rupesh Sarkar, Wikimedia Commons

[…] Also Read: Brewing in Uncertainty: The Lives and Livelihoods of North Bengal’s Tea Plantation Workers […]