Written by K. Hariharan

Cinema in the 20th century was the most dominant form of popular culture across the world. Simultaneously, it was considered the most disruptive and anti-social element in every society. So much so, that the Women’s Christian Temperance Movement protested against silent cinema for its alleged capability to destroy the minds of young boys and girls.

Mahatma Gandhi, who had never been to a cinema theatre, said, “But even to an outsider, the evil that it has done and is doing is patent. The good, if it has done any at all, remains to be proved. If I had my way, I would convert all cinema theatres into cotton spinning halls and factories for making handicrafts.” In most Islamic nations, cinema is still not kosher.

But why was cinema, but not print or radio, endowed with such a reputation?

Of the People, For the People

For starters, the first film audiences were primarily from poorer working classes. Film was a new way to consume low-cost entertainment. Knowing their clientele, producers provided content that did not require much scholarship. Second, content had to be relatable to these audiences. Scripts most often featured a downtrodden hero fighting the system to claim a rightful share in the modern enterprise of democratic nation-building.

Eventually, this avenue of opportunity compelled the educated classes to lend their expertise to film as screenwriters or music composers. Thus, the scholarly citizen and the commercial entrepreneur joined hands and soon drew the so-far reticent educated middle class into cinema halls.

Some Hollywood moguls were convinced that the only way to elevate cinema was through big museums. They moved to transport film from ‘low’ to ‘high-art’. The Museum of Modern Art was roped in and director Iris Barry agreed to screen “good” American films in the museum. They even bought select prints to be stored in their haloed vaults alongside the likes of Van Gogh and Rodin.

Across the world, cinema had now become ‘big business’. For the burgeoning urban middle and lower-middle class, cinema was the only source of global information and entertainment.

How to Train Your Filmmaker

To supply a regular flow of quality-entertaining scripts, big studios needed an army of full-time wordsmiths slogging perennially. At the time, no university could provide the particular kind of thinkers required for this job.

Traditional communications colleges couldn’t keep up with the constant technological changes as silent cinema transitioned to talkies. The dangerous combination of an artistic medium and technology left most academicians baffled. Was cinema the ultimate art or a definitive science? Could such skills be taught in a classroom within a three-year curriculum? Would a graduation in this field hold any promise of success at the box-office? Would it be better to nationalize cinema so that all its players could be brought on a level playing field?

Broadly speaking, film education sped in three distinct directions:

For one, Hollywood film veterans collaborated with big universities like UCLA and NYU to run courses to train production interns. Traffic in and out of studios was regulated by an elaborate ring of unions and pricey agents.

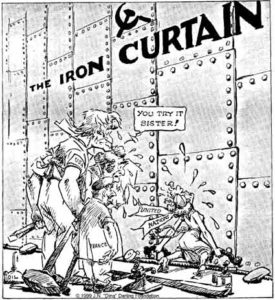

On the other hand, in the Soviet Union, China, the erstwhile East European nations, and to an extent in France, UK, and Sweden, film schools were state-run. Here, students were encouraged to think critically but not enough to question the establishment itself.

Filmmakers were provided state funds to produce content that furthered nationalistic pride and employed talented art-oriented aspirants. These films never had to vie for success at the box-office but had to be good enough to screen at international film festivals. The makers additionally had to volunteer to spend time mentoring students at the State film schools.

From Campus to Cannes

A third trend emerged in countries like India – trapped between capitalist behemoths and socialist vanguards, the onus of training filmmakers rested on the government. The big studios such as Modern Theatres in Salem, Vijaya Vauhini in Chennai, and Raj Kapoor Studios in Mumbai did constantly churn out scripts (pejoratively called ‘masala’ formulas) at regular story-writing workshops. But the State shouldered primary responsibility…

The first official state-run film school began functioning in 1940 in Bengaluru under the stewardship of Maharaja Jaya Chamarajendra of the erstwhile Mysore State. It is at this humble polytechnic campus that my father, affectionately referred to as Kodak Krishnan by Indian filmmakers, and other celebrated cinematographers such as VK Murthy and NV Srinivas emerged in 1947. It remained state-run even after 1950.

But the central Information and Broadcasting Ministry had to justify its presence with tangible results. Documentary/propaganda cinema was put on a pedestal; the Films Division became a collective of cine-technicians and self-trained scriptwriters singing paeans of praise in the name of Bharat Mata.

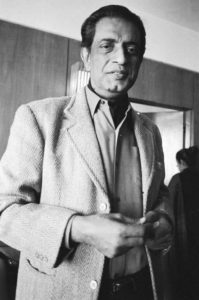

And then something happened in 1955. Satyajit Ray’s low-budget film Pather Panchali was awarded at the Cannes Film Festival that year, which suddenly put India on the cinematic world map. The government was charged; plans were afoot soon to set up an Indian Motion Picture Export Corporation (IMPEC) and a Film Finance Corporation (FFC) to assist filmmakers venturing into the world market.

The iconic train-chasing sequence in Pather Panchali. Source

Behind the Camera

Soon after, filmmaker Marie Seton found herself meeting Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru during her quest to understand India. She was a close associate of renowned Soviet filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein. This prompted Nehru to ask her to develop a plan to engender a progressive film culture in India. During this process, she met with three crucial personalities who set the tone for a scholarly point of view for Indian cinema – Satyajit Ray, film aficionado Satish Bahadur, and head of the Indian Film Society movement Chidananda Dasgupta.

The common thread uniting the three men was their love for ‘realistic’ cinema and their complete contempt for the commercial masala mainstream Indian cinema. Together with Seton, they took over the near-bankrupt Prabhat Studios in Pune under the I&B Ministry. It came with shooting equipment, sound studios, and a processing laboratory – all of which they decided to use to kick-start a culture of realistic cinema in India. Thus, they established India’s first national film school in 1963 – the Film Institute of India (renamed Film & Television Institute of India (FTII) in 1973).

With a minimum focus on the technical craft of filmmaking, there was greater emphasis instead, on the appreciation of quality cinema. However, this aesthetic exercise did not sit well with the University Grants Commission or the Technical Education authorities, who were used to the scientific rigour of IITs. The curriculum was not even at par with Fine Arts colleges at the time. Moreover, faculty members didn’t have formal qualifications and were recruited solely for their individual talent/capacity. For all these shortcomings, the institute was condemned to awarding diplomas and not Masters degrees in cinema.

Unlike institutions like Gautam Sarabhai’s National Institute of Design (NID), FTII did not have a grand mentor associated with it. Consequently, it was just seen as a placement agency for the ill-reputed film industry. To make matters worse, the various IITs and engineering colleges did not see ‘Film Technology’ as worthy of being taught in classrooms. Degree courses in everything from printing to plywood manufacturing were common, but designing and manufacturing the technological devices required to run film studios and cinema theatres were inexplicably considered as worthless pursuits.

In a country that consistently churns out more films than any other, every piece of equipment in use has to be imported. Even ordinary digital projectors and sound speaker systems have to be procured from elsewhere because indigenous institutions still don’t acknowledge such technical know-how as valuable.

Behind the Script

And thus, the saga of Indian film education was stymied from both ends – it was devoid of both technical insight and a strong foundation in the world of Arts. If the lack of technical training was a significant obstacle, the intellectual input was just as disappointing.

FTII’s syllabus functioned more as a film-appreciation course. Students believed they could easily learn to make films just by (a) watching the European masters, (b) discussing their ideas over endless cups of tea flavoured by a steady supply of beedis, (c) cursing the popular commercial/entertaining films and on a lighter vein, and (d) growing long beards as some form of protest against neat-looking job-seekers.

Even by the end of the 20th century, FTII couldn’t establish a culture of successful quality filmmaking, as was envisioned. The school had been annually churning out 50+ film graduates since 1966, yet only a handful of those ~1700 individuals made a mark in the world of cinema.

While the Center was still relatively unconcerned, a few state governments did take initiative. Tamil Nadu, Orissa, Kerala, and West Bengal set up film schools. Unfortunately, all of them were infected by the very same virus. They borrowed the FTII syllabus, staffed classrooms with FTII alumni, and depended on government aid to carry out rather expensive training programs for no more than diplomas. Soon, the funds were only enough to break even, leading to constant unrest.

Kal Aaj Aur Kal

Things have been changing since the arrival of prosumer video cameras and digital technology in the early 21st century. Most Mass Media communication colleges began offering filmmaking courses as part of their Arts or Science degree courses. To capitalise on the rising demand, numerous private film schools cropped up across the country.

I myself helped establish and became founder-director of the LV Prasad Film & TV Academy in 2004. FTII alumnus Subhash Ghai set up a similar school in Mumbai in the same year.

Our schools modified the FTII syllabus to make it less aesthetic-driven and more craft-driven. We believed that understanding the aesthetics of cinema could not be imbibed through classroom lectures but only through constant practice and self-critique. Our philosophy for the next generation of Indian filmmakers was to instil a culture of learning one’s lessons and make necessary corrections on the daily.

The new motto: A film school can never teach how to make a film but it can always help you learn how to make a film.

In this day and age, everybody with a camera phone is a filmmaker. The anti-social element of the early 20th century has now become a standard requirement of social media today. In such an ecosystem, where do film schools fit? What is the purpose of instructing filmmaking in classrooms when everyone is a filmmaker on the streets?

Featured image courtesy Nemai Ghosh