Written by Ayush Jain

Ever since Independence, the educational indicators of India’s Scheduled Tribe (ST) population have been much lower compared to the rest of the populace. A wide range of factors such as economic hardship, language barriers, cultural discrimination, and a shortage of teachers account for this phenomena. Owing to the ambiguously defined ‘differences’ of tribal populations located in remote areas, both the Dhebar and the Kothari Commissions suggested creating an ‘alternative’ educational framework from the ‘mainstream’, that catered to the specific contexts and needs of ST populations.

Following measures like reservations and other residential educational establishments enacted by the State for ST students, the Ministry of Tribal Affairs (MoTA) launched the Eklavya Model Residential School (EMRS) scheme in 1997. The EMRSs aim to provide free education to ST students across the country, through residential upper primary and secondary schools (class 6th to 12th). Admission is on the basis of a selection examination (the EMRS ‘Entrance-test’), with provisions in place for children belonging to ‘Primitive Tribal Groups’, and first-generation students. The scheme also outlines an equal number of seats for both boys and girls, with a vision to nurture the holistic development of all tribal children, and improve their hitherto educational and socio-economic backlog within the Indian nation-state.

The establishment of 462 new ‘Eklavya Model Residential Schools’ (EMRs) in blocks with more than 50% ST population and at least 20,000 tribal persons across the country is an excellent approach to impart quality education to children. #TransformingIndia pic.twitter.com/Dw4jFmIN5w

— Chowkidar Dr. Ashwathnarayan (@drashwathcn) 2 January 2019

In a bid to bolster the comprehensive development of EMRS students, the MoTA has been involved in organizing several extra-curricular activities and national-level inter-school opportunities (such as the 1st inter-EMRS sports meet held at Hyderabad in 2019) for them. Some EMRSs, run on a Public-Private-Partnership model with experienced organizations (including Art of Living!), showcase success stories of tribal students getting into IITs and IIMs, and clearing the UPSC exam with flying colours. While such a state of affairs—incidentally disseminated entirely by government press releases—paints a rosy and promising picture for educational development in India, there is more than meets the eye. In some cases, the poor functioning of EMRSs, and indeed the legacy of the residential model, result in the perpetration of forms of cultural violence.

Implementational Shortcomings

Infrastructural failings highlight the distance between the policy framework and the functioning reality. In the case of Odisha’s EMRS schools, for Dr. Amarendra Das, Reader of Economics at NISER, Bhubaneswar, a lot of groundwork remains to be covered. “Although the policy framework of the EMRS scheme conceptually sounds good, the reality is far from satisfactory. EMRSs are suffering from problems similar to those faced by general government schools.”

This is further corroborated by a 2015 study conducted by Manav S. Geddam in an all-girls’ EMRS in Andhra Pradesh. A lack of toilets, laboratories, and several other built facilities was noted. Additional maintenance problems (owing to an absence of a well-defined budget) persevered, as did instructional limitations (such as the desire of students for subject-coaching and additional teachers). Despite Central grants being apportioned to the States/UTs under Article 275 (1) of the Constitution to run the schools, the EMRSs often suffer from funding delays or, as Dr Das says, an ‘inadequacy of funds’.

The prevalence of such issues in certain regions stem from inefficient monitoring of the schools themselves. The School Management Committee (SMC) has the responsibility of regular evaluation of EMRS schools. The incompetence of the SMC in the case of some EMRSs partially stems from a lack of awareness of SMC members of their responsibilities. Says Dr. Das in the case of Odisha, “SMCs rarely function effectively. Members of SMCs stay far away from the schools. They are neither able to attend meetings of the SMCs nor track the functioning of the schools. Many times it is also observed that teachers are also not very interested in the active functioning of the SMC.”

According to Stanley V. John, a member of DIET Bastar speaking in the context of Chattisgarh’s EMRSs, there is a need for a much stricter “system of monitoring and assessment” in the schools than what already exists to remedy such shortcomings. A vigilant SMC could also shed light on a quiet, yet concerning phenomena in some EMRS schools — acculturation.

Bottlenecked on the Strings of Cultural ‘Supremacism’

Children often find themselves alienated from their home environments in any residential school. However, when alienation is grounded in what John observes in his experience of EMRS schools to be a “disrespect for tribal language and culture”, a cultural divides set in, permeating classrooms and campus atmospheres. Looking specifically into such residential institutions across the country brings to light how cultural majoritarianism works to acculturate supposedly ‘backward’ peoples.

Ultimately, what does residing in a hostel and being educated away from home mean for a tribal child? Is the focus on assimilatory integration or acculturation? The Geddam study highlights that there is an earnest concern for communication and visitation rights (during birthdays and festivals) from both the students and their parents. For Dr. Uma Maheshwari Chimirala, an Assistant Professor at NALSAR University of Law currently working on a research project with young multilingual tribal learners of Pota-Cabin Schools in Chhattisgarh, this creates a cauldron of space between parents and their children. Chimirala suggests that this not only deprives children of parental care, but is also an example of the state wielding its power into the family-state space in the case of tribal children.

This is largely because the EMRS school model, amongst India’s other residential school programs for ST students, are the legacies of colonial policy interventions world over to ‘civilize’ tribal populations, through educating them in ‘civilized’ dominant cultures. These schools fulfilled this mission, by violently separating children from their families, to create new generations of ‘civilized’ citizens.

For Dr Das, “the idea of mainstreaming is the first and foremost colonial legacy still continuing in framing the educational policy for tribals. Sensitivity towards the language and culture of tribal children is not reflected in the policy-making and implementation [of EMRS schools].” Direct and indirect practices of systemic discrimination in these spaces–such as prohibiting tribal languages and cultures while imposing ‘mainstream’ languages (like Hindi and English)–implicitly work towards eroding tribal identities and cultures, as opposed to developing and promoting them. This has far-reaching deleterious effects on tribal cultural practices.

Sensitizing Pedagogies

The National Curriculum Framework (2005) states the importance of integrating a culturally sensitive pedagogy while imparting education. Yet, currently, the State in its attempt to address ST educational outcomes in the residential educational model ends up both directly and indirectly encouraging assimilation into a larger hegemonic educational culture.

“We don’t appreciate what is already there and build on that.” — Ravi Rebbapragada, Executive Director of Samata, an Andhra Pradesh-based NGO working towards tribal rights

As The Bastion has previously noted, education in lucrative ‘foreign’ languages and cultures affects education and the depth of learning itself. Without a firm grasp over their mother-tongues, ST children are ushered into homogenizing national education systems, and taught in dominant languages. Ironically, this could negatively impact the indicators that the EMRS schools are attempting to change.

For Dr. Chimirala, this can be best addressed by reorienting the teacher-training framework in the country. According to Chimirala, “the medium of education [in India] happens to be languages which are uncritically presumed to be ‘useful’ for mobility [like English or Hindi].” Teachers are trained to teach children in these ‘useful’ languages alone, to the disadvantage of tribal children who are often unfamiliar with them. Says Chimirala, there is a need to “engage with bilingual pedagogical approaches,” that accommodate for differences in cognition and learning styles in the classroom.

Pedagogy itself can be reimagined keeping in mind tribal culture to improve grasp over concepts, as well as educational indices. Teachers need to be advised on how to develop contextualized ‘pedagogy in action’, by making use of familiar cultural motifs. For example, during her research, Chimirala observed a teacher in a tribal residential school successfully explain the concepts of Wind and Force using a bow-and-arrow to her students.

Beyond assimilation, such policies also consolidate our definitions of national culture. How we conceptualize useful pedagogy and cultures within the classroom itself needs to change. Says Das, “The culture of Adivasis should get a place in the so-called ‘mainstream’ education curriculum. The curriculum for all levels should be intercultural.” Failing to develop pedagogies reflective of India’s diversity only furthers what is fast becoming a homogeneous educational ‘mainstream’ under the Centre, the same organ that supposedly aims to further ST interests.

The Road Yet To Be Taken

With a revamped budget of Rs. 2,242 crore approved by the Cabinet in December of 2018, the EMRS scheme proposes to take on some of its infrastructural and resource limitations with a consolidated per capita flow of funds. Yet, although this increased intervention tries to address financial shortcomings, all-important cultural concerns remain unanswered.

Active steps towards developing contextualized and individualized learning processes are required, while the concept of residential education itself for ST students—in light of its problematic past and present—must be reimagined. A cultural bridge that infuses the State’s proposed policy objectives with the traditions and rights of India’s diverse ST populations, is the call of the hour.

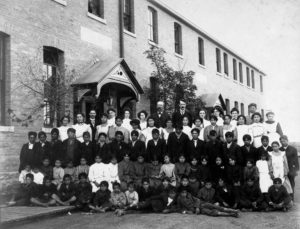

Featured image courtesy of the Odisha Model Tribal Education Society.

[…] week, The Bastion’s Ayush Jain delved deep into the Eklavya Model Residential School (EMRS) system. Set up by the […]

A thought provoking read!

Very insightful.

Well written!