I. Rising Sea Levels Escalate Adaptation Concerns for the East Coast of India

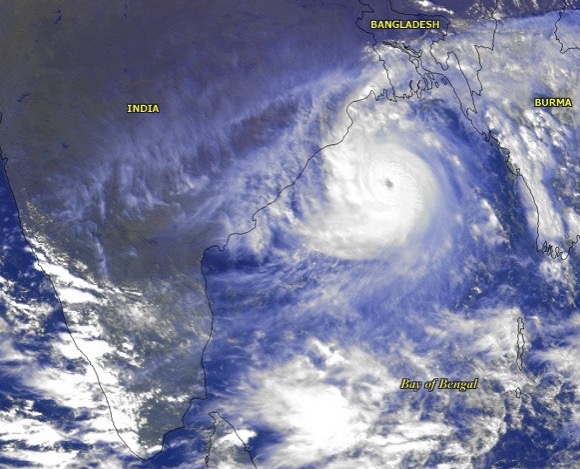

Coastal areas are among the ecosystems most critically affected by climate change. A recent study finds that the projected rise in sea levels is bound to increase the frequency of coastal flooding from a 1 in 100-year event, to once in 10 years by 2100. The IPCC’s Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate predicts that the continued warming of the ocean will increase the severity of tropical cyclones, exposing many low-lying coastal areas across the world to inundation, storm surges, and coastal erosion. India’s coastal region, especially the low-lying stretches of the east coast, is already witnessing the worst of these climate stresses.

Every year, the east coast of India is ravaged by cyclones which develop in the low-pressure systems of the Bay of Bengal. The concave-shaped geomorphology of the bay makes it conducive for the formation of catastrophic storm surges that frequently make landfall on the east coast. Odisha, located at the head of the Bay of Bengal, is a region most vulnerable to this cyclonic activity: it has witnessed seven major cyclones in the last 50 years.

The state has suffered some of the worst cyclones in history, including the 1999 super cyclone which killed close to 10,000 people and displaced nearly a million others. In 2013, the state was struck by an extremely severe cyclonic storm Phailin, which caused up to ₹400 crores in losses and claimed nearly 30 lives. In 2018, the state was hit by two cyclones within a span of three months—cyclone Titli which affected close to 60 lakh people, and cyclone Phethai which displaced nearly 20,000 people. This was closely followed by cyclone Fani in 2019, said to be the most severe storm since 1999, which caused a death toll of 64 and estimated losses of ₹12,000 crores. The adaptation of these ecosystems and communities to climate change-induced rising sea-levels is no longer a question for the future, but a matter of immediate concern.

II. Coastal Erosion in Satabhaya, Odisha: The Story of Our Climate’s First Orphans

Satabhaya, a coastal village located in Kendrapara district, is one of the foremost victims of coastal erosion and submergence due to rising sea levels. In fact, the 17 km stretch of Satabhaya beach is said to be among the fastest eroding beaches of Odisha.

The once idyllic coastal village used to be a cluster of seven villages, or ‘seven brothers’. Inhabiting these lush floodplains was an agricultural community of about 3,000 people who cultivated paddy and fished in the local freshwater ponds. “In Satabhaya, our lands were blessed with the most fertile alluvium. We never used any chemical fertilisers or pesticides. We never had to purchase anything apart from cooking-oil for our needs,�? says Netrananda Behera, a former resident of Satabhaya.

Since the massive cyclone of 1971, six of these villages—Gobindapur, Mohanpur, Kanhupur, Chintamanipur, Badagahiramatha, and Kharikula—slowly began to disappear into the sea, one after another. Today, as the rate of coastal erosion swiftly escalates, Satabhaya faces a fate similar to that of its six brothers. Unable to cope with the loss of their homes to the sea and their lands to saline ingress, year after year, an increasing number of families migrate away from the hamlet. The ones that choose to remain, retreat inwards, away from the sea. “We have shifted our huts four times in the last ten years. Since our sandhills disappeared, the sea began to lash out at us stronger than before. We are completely at the mercy of the sea,�? says Pushpalata Malik, a sharecropper residing in Odasala, a strip of land behind Satabhaya.

The Government of Odisha commenced efforts to rehabilitate the people of Satabhaya in 1992, after the super cyclone. After several failed attempts, the Satabhaya Resettlement and Rehabilitation Yojana finally came into effect only in 2011, to shift 571 families to the colony of Bagapatia, 12 kilometres from Satabhaya. However, the allotment of land in the colony was based on surveys undertaken in 1992, and did not account for younger generations who had in the meantime grown and raised their own families. As a result, most of the area’s youth (who found no place in the rehabilitation policy) have migrated in search of livelihoods, seeking employment as unskilled workers or daily wage labourers in other parts of the country. “My son works in the plywood factory in Kerala. He was not allotted land in the rehabilitation colony as he was a child when the tehsil office conducted the survey,�? says Kamalakar Swain, who ferried the villagers across the backwaters, between Satabhaya and Bagapatia.

III. Human Contributions to the Climate Catastrophe: Neglected Feedback Loops Within Complex Ecosystems

While Satabhaya is a prime example of climate change-induced coastal erosion—a phenomenon that is ferociously overtaking the coastline of Odisha—it is less understood as a man-made ecological disaster.

90 kilometres south of Satabhaya, the port town of Paradeep located in Jagatsinghpur, was inaugurated in 1962 by Jawaharlal Nehru. Embodying the vision of the “maker of modern India�? himself, the port town was to be developed into a hub of industry and commerce. The stone breakwater that was installed at the Nehru Bangla in 1962 stands as the foundational monument to the coastal development that followed in Paradeep.

The coastal landscape of Odisha is shaped by a complex overlay of mudflat and sandy beach ecosystems. They not only perform critical ecological functions such as regulating the sediment transport on the coast, but also serve as natural defences against the sea. The disruption of these defences in the wake of construction and population growth can adversely impact the susceptibilities of the coast to cyclones.

In the case of Paradeep, the installation of the sea wall and the consequent denudation of the natural mangrove forest-cover to expand construction along the coast, closely coincided with the aggravated effect of high tides on the sand dunes of Satabhaya. Additionally, the ill-advised decision of the Forest Department to undertake Casuarina plantations, without studying the impact of these non-native species on the local ecosystems, arrested the development of sand dunes on the beach. The strikingly unequivocal consensus prevalent among locals in Satabhaya on these knock-on effects also finds support in scientific studies on the shoreline impacts of sea-walls in India. These studies confirm that in several cases, when used as a stand-alone measure, sea-walls have resulted in active or passive forms of coastal erosion.

The plight of submersion is by no means unique to the case of Satabhaya, but is an imminent threat facing several villages along the coastline. In the wake of cyclone Fani in 2019, the village of Rameyapatnam in Ganjam was rendered defenceless against high tides. Perched literally on the brink of the sea, the lives and livelihoods of the traditional fishing community in this village hang in peril as the waves eat away at their homes, forcing them to relocate to the hinterland.

IV. Fragmentation of the Ecological Landscape: The Limits of India’s Coastal Adaptation Paradigm

IV. Fragmentation of the Ecological Landscape: The Limits of India’s Coastal Adaptation Paradigm

The Government of Odisha spends crores of rupees every year on disaster relief due to cyclones. With the projected rise in sea levels and the increasing intensity of cyclones brewing in the Bay of Bengal, strengthening the adaptive capacities of coastal ecosystems and communities is one of the core concerns of coastal management and planning. The story of Satabhaya tells us that the vulnerability of the coast is forged by the compounding effects of the biophysical risks posed by climate change, and the economic and demographic pressures placed on the ecosystem. Therefore, for any attempt to strengthen the adaptive capacities of the coast to be successful, it must demonstrate a refined understanding of the non-linear impacts of multiple stressors across spatial and temporal scales.

However, adaptation approaches in India have elicited a narrow articulation of the problem where the focus lies on disaster mitigation or adaptation outcomes with immediate, tangible benefits. Take, for instance, the Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) model that was adopted by the Ministry of Environment, Forest, and Climate Change in 2010. Funded by the World Bank, this model sought to provide a policy design for coastal development grounded in sustainable practices. Having implemented a series of coastal and marine adaptation projects in its first phase of operations in Odisha, Gujarat, and West Bengal, ICZM currently serves as the basis for a prospective National Coastal Mission as part of India’s Climate Action Plan (NAPCC, 2014).

The ICZM phase I adaptation projects implemented in Odisha have largely taken the form of infrastructural projects and community-based livelihood interventions. These projects were executed within the framework of the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Notification, 2006 and the Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) Notification, 2011, that together serve as the centrepiece of coastal regulation in India. Notified under the framework of the Environmental Protection Act (EPA), 1986, the CRZ regulates coastal areas by classifying them into 4 zones with clearly prescribed levels of human activity, while the EIA mandates environmental clearance for any proposed economic activity or the expansion of an existing activity.

Since their inception, these regulations have been widely criticized for systematically eroding ecological safeguards against the unchecked expansion of human activity on India’s coasts by persistently granting concessions in favour of exploitative development. Built on a feeble foundation of coastal regulation steeped in a highly insulated sectoral administrative set-up, the ICZM model of adaptation provides little scope for the kind of nuanced understanding of overlapping dynamics that coastal ecology demands. The following examples of ICZM adaptation projects implemented in Kendrapara and Ganjam illustrate the limitations of such a model.

IV.I. Structural Adaptation Interventions: The Geosynthetic Tube Project

The village of Pentha in Kendrapara has suffered a spate of erosion similar to Satabhaya, which has only worsened over the last decade. As high tides dealt irreparable damage to the embankment protecting the village, it became the chosen site for the pilot ICZM geo-synthetic tube project. The project was sanctioned by the Department of Water Resources of Kendrapara in 2013. It was characterised as a “soft protective�? measure made of geo-tubes filled with sand, encased in a granite armour. Unlike a hard measure such as a granite sea-wall or a breakwater, geotubes are packed with sand and organic material and placed parallel to the sea-front in order to absorb the tidal ingress rather than deflect it. This project proposed to install 241 geotubes to protect the cluster of settlements along the coastline.

Although it was intended to provide protection to 56 villages, the length of the wall post-construction was only 500 meters. However, by the time it was completed in 2017, it incurred a massive expenditure of nearly ₹40 crores. The structure sustained severe damage and raked up maintenance charges amounting to ₹1.9 crores within a month of construction. The villagers in Pentha were unconvinced of its value, having witnessed the structure fall apart multiple times during the course of its installation. They had no stake in or involvement with the project, other than having had their land acquired by the government for the construction after a perfunctory consultation process. On the contrary, there were instances of vandalism and local animosity towards the construction which raises questions about the efficacy of such top-down solutions for coastal adaptation.

Moreover, despite being a soft measure, there appeared to be no perceptible difference between the impact of the geo-tube wall and a conventional sea-wall on the ecosystem. On the other hand, climate experts have found such structures implemented in other parts of the country to have interfered with and even arrested crucial ecological processes, such as beach nourishment and sand-dune formation.

IV.II. Community Livelihood Adaptation Measures: Solar Fish Drying Units

The town of Gopalpur in Ganjam was another location chosen for the installation of an ICZM phase I project- solar-powered fish drying units. This project was launched in 2014 under the sustainable livelihood initiative of the ICZM to enable fisherwomen to earn a living during the lean-fishing season, by selling packaged dry fish. Around 30 fish drying cells were installed with solar-powered drying equipment to be operated by the fisherwomen-collective or self-help group (SHG).

The project incurred an expense of ₹35 crores for its construction. According to local sources, however, the equipment fell into disuse within two months of being installed due to mismanagement and misappropriation of funds allotted for its maintenance. In theory, the project was a well-directed attempt at community adaptation. It was to create a stable source of income for the local fishing community that would help them cope with frequent losses from the cyclone, an irregular and steadily depleting haul of fish year after year, and seasonal fishing bans.

However, in reality, it failed to create value or garner the acceptance of the community as it was entirely detached from their actual needs. “The local fish species that have a high demand here is not even suited to drying in this equipment. We barely made enough money to pay monthly rent on our shops through those sales,�? says Parvathi, a member of the women’s self-help group. Krishna, a small-scale fisherman currently struggling to earn a living concurs. “What is the point of spending crores of rupees on fish drying units when the government cannot provide us with the most basic fishing equipment like nets, motorised boats, or fish landing sites?�?

The deteriorating viability of traditional fishing and the failure of alternate livelihood initiatives have pushed much of the younger generation of fishermen away from the occupation. The state government’s attempt to sustain them through liquid cash flows and benefit schemes such as the 1 Rupee/kg rice scheme have introduced impractical dependencies and inertia within the community. This is evident from a perceived rise in idle pursuits such as gambling and alcoholism within the community.

V. Anchoring Adaptation Pathways in Systems-thinking

V. Anchoring Adaptation Pathways in Systems-thinking

The lessons of Satabhaya go unheeded as the knock-on effects of geotube walls on coastal dynamics remain understudied. The systematic rupture of the relationship between traditional fishing communities and the coastal ecosystem remains poorly understood. Meanwhile, the state government prepares to undertake a second phase of ICZM projects in addition to obtaining funds for new projects such as Enhancing Coastal and Ocean Resource Efficiency (ENCORE), building on the ICZM phase I model.

Consequently, we are bound to witness more such fragmented structural and community-based adaptation interventions. The damaging effects of such ad hoc adaptation efforts alone, not even accounting for the pressures of continued commercialisation of the coasts under blue economy ventures such as the Sagarmala project, portend calamitous consequences for the well-being of the ecosystem.

The root of this fragmentation of lives and life forms that we witness across the coast, be it in Satabhaya, Pentha or Gopalpur, lies in a pernicious and exploitative developmental design that fosters a systematic disconnect between interdependent elements of the ecosystem. While disaster mitigation efforts and technical and technological solutions such as the ones seen above are crucial forms of adaptation, they only address symptoms of a weak ecosystem while entrenching persistent and intractable patterns of vulnerabilities. Recent advancements made in the science of ecological resilience and systems-thinking have emphasized the limitations of such a one-dimensional paradigm that limits adaptation to a set of discrete policy or technology choices, skewing priorities away from the long-term viability of ecosystems. These developments in ecological research have forged remarkable pathways for broadening the scope of adaptation, formulating it as an issue of ecosystem resilience instead.

Faced with some of the most difficult decisions concerning its coastal resources in the near future, it is time for the adaptation policy discourse in India to expand beyond the disaster paradigm and incorporate issues of ecosystem resilience. Ongoing projects such as Disappearing Dialogs implemented in West Bengal, which explore the narratives of community-based ecosystem restoration in the East Kolkata Wetland, appear to offer an alternative towards such a paradigm shift in coastal adaptation. However, with the unmitigated exploitation sanctioned by the CRZ, 2019 notification coupled with the latest draft of the EIA notification, India still has a long way to go to achieve such a paradigm change.

Text and photographs by Anvita Dulluri, reproduced with permission | Views expressed are personal.

[…] have spelt disaster for coastal communities. We’ve seen such knock-on effects on India’s eastern and western coasts. Even adaptive measures the state has implemented in the Hindu Kush Himalaya […]

[…] have spelt catastrophe for coastal communities. We’ve seen such knock-on results on India’s eastern and western coasts. Even adaptive measures the state has carried out within the Hindu Kush Himalaya […]