As humanity struggles to stay standing after the knock-out punch delivered by COVID-19, it may be useful to look at how we survived previous disasters to understand how to not only outlive this one, but be better prepared for future ones.

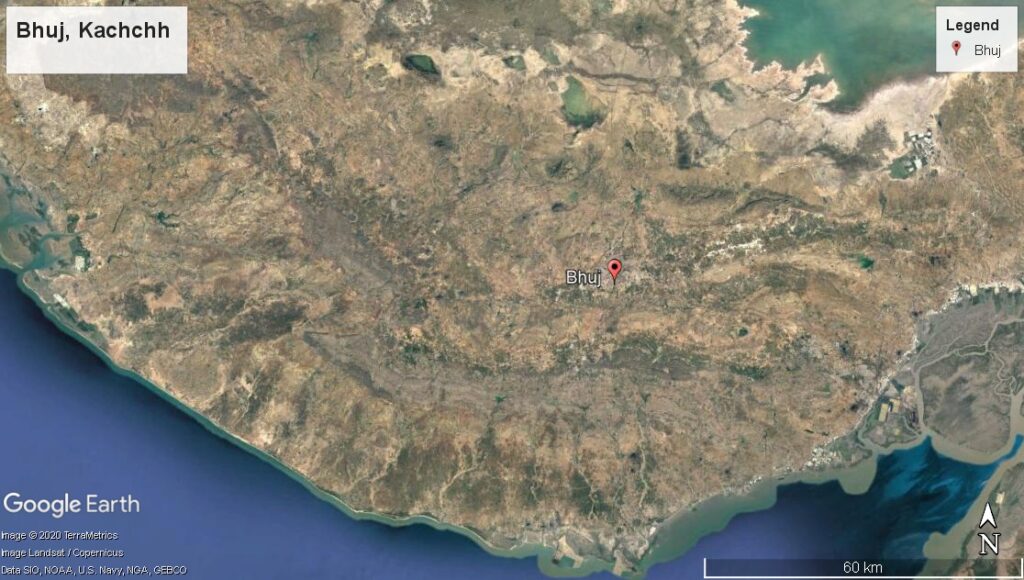

Take the example of Kachchh, in Western India. Between 1998 to 2001 Kachchh was devastated by two cyclones, drought, and a massive earthquake. Thousands of people died, while tens of thousands lost their homes and livelihoods. Yet over the years, the region has witnessed remarkable reconstruction. Its significance for the COVID-19 crisis is not because the two disasters are similar, but because their fallout is.

During state-imposed lockdowns, the greatest distress is faced by migrant and daily wage labour, street vendors and other small traders, as well as primary producers like farmers, fishers, pastoralists, craftspersons, and forest-workers who cannot access their natural resources or the markets they sell their produce in. This has exposed the massive faultlines of a highly unequal society, where only a minority can continue to work from the safety of their homes. Hundreds of millions cannot afford to and have few social security systems to fall back on.

What post-2001 Kachchh shows us is the potential to build dignified, sustainable livelihoods grounded in local economies and community governance, that can significantly reduce the vulnerability of these millions.

The Kutch Navnirman Abhiyan

Amongst the many governmental and civil society initiatives that sprung up in Kachchh after the first cyclone, perhaps the most innovative was the Kutch Navnirman Abhiyan (or Campaign for Kachchh’s Reconstruction). Over a dozen civil society organisations (CSOs) working on various aspects came together to organise enormous relief and rehabilitation measures for hundreds of villages. Amongst these were the Kutch Mahila Vikas Sangathan (KMVS), Sahjeevan, the Vivekanand Research and Training Institute (VRTI), and several others.

Together, they surveyed all of Kachchh’s 580 affected villages, to direct governmental and non-governmental relief measures.

One of the survey’s most important findings was the loss of the means of production for locals, through damage to materials used in crafts and agriculture. As people migrated out of their traditional settlement to find work, there was also the weakening of self-confidence and social ties.

So, most important in the initial years of the Abhiyan, says one of its founders Sandeep Virmani, was “the firm belief that post-disaster initiatives had to be oriented towards rebuilding local self-confidence and capacity for people to rebuild their lives. Charity alone would not do, indeed it would only perpetuate a state of dependence that would mean that the next time disaster struck, people would still be unprepared to face it.”

The Abhiyan also found that strong local cultures of resilience, solidarity, and entrepreneurship could be tapped into to deal with the crisis.

What followed has been a remarkable story of reconstruction, not only of physical and material means of living, but also of knowledge, pride, self-confidence, and will.

Of key relevance to this is the Abhiyan’s philosophy, wherein “The objective of the network is to synergize human knowledge, physical & financial resources to collaborate towards a Kachchh which is governed by community initiatives. The network encourages self-help development, especially with marginalized sections, integrates traditional wisdom with new technologies and innovates and balances issues of human rights with human responsibilities.”

Building on this, various constituents of the Abhiyan focused on different aspects of reconstruction, from the empowerment of women and of other marginalised sections, to the regeneration of nature and natural resources, and the revival or sustenance of the region’s immense craft diversity.

Reviving Crafts in Kachchh

Well before the Abhiyan began in the 1980s, a craft revival initiative, Shrujan, had been demonstrating the possibility of generating home-based livelihoods since the early 1970s.

Its founder, Chanda Shroff, noticed the amazing embroidery craft of the region when touring drought-stricken villages. Detailed studies revealed different kinds of community-specific embroidery (pastoralist, farming, trading, etc), including motifs on gender, age, marital status, and social status. Shrujan facilitated the conversion of using these skills for not only domestic products, but for the market too.

When the Abhiyan was formed in 1998, Shrujan also joined the post-disaster relief. Now, over 3,500 women from over 120 villages are part of the Shrujan process, earning decent livelihoods from their own settlements rather than having to migrate for work.

The Shrujan ethos of craft revival has been witnessed across communities in Kachchh, such as the Ajrakh, or, block-printing Khatris who after the earthquake, were displaced from their villages. Under the leadership of Ismailbhai Khatri, the families converged near Bhuj in Ajrakhpur, a new settlement named after their craft, and transformed the region into a thriving hub of block-printing.

Taking this story further, Kachchh’s vankars–handloom weavers–have also transformed impressively, thanks to the crafts design centre Khamir and some handloom design schools.

The community had previously faced a severe decline in demand thanks to mass-produced industrial products from Ludhiana and elsewhere. The weavers were further dealt a severe blow by the natural disasters. However, when weaving was revived around 2005-6, as per former Khamir director Meera Goradia, it was because “of the creation of a complete value chain using locally grown, organic Kala cotton to make wonderful products, and [the] leadership and innovation shown by some weavers.”

15 years later, the craft is robust enough to attract young men from the community to restart it, many of whom have left jobs in industries or the Gulf. Besides economic incentives, the men find an equally important pride in continuing their family heritage (not to mention the comforts of sitting at home and working and being their own bosses!) When queried about why he had not gone into IT, young carpet weaver Prakash Naranbhai Vankar quietly asserted “my loom is my computer”.

Throughout this process of community-level reconstruction led by the Abhiyan, a number of positive changes in caste, gender, and age hierarchies have been brought about. For example, it has enabled young vankar women to sit on the loom (traditionally not allowed) and express their creativity.

Bridging the Governance Gap

Crafts are of course only one aspect of people’s lives and livelihoods. Food, fodder, water, housing, energy, sanitation, health, education, and other needs also need to be met. It is the lack of these facilities, or the lack of access to them for some marginalised groups, that forces people to migrate out, making them doubly vulnerable during crises like the COVID-19 lockdowns.

Several other organisations who founded the Abhiyan or emerged from it, have focused on some of these basic needs and aspirations. This has helped create more local economic activity, and reduced the lack of access to infrastructure which forces outmigration.

For instance, Sahjeevan, VRTI, and Arid Communities and Technologies (ACT), established in 2004, have enabled decentralised water harvesting and governance in dozens of Kachchh’s villages and in Bhuj town. This program includes training local youth to be parageohydrologists. In Abdasa taluka alone, over 100 villages with 40,000 people have benefited through a programme called Paani Thiye Panjo. This is no mean feat in one of India’s lowest rainfall regions, subject to periodic droughts.

Then, there’s Kachchh’s maldhari (pastoral) community, who depend on the region’s grassland ecosystems home to a large population of diverse livestock. The maldharis pasture lands have been encroached upon time and again by industries and agriculture.

With help from Sahjeevan and other groups, the maldhars mobilised under the Banni Pashu Uccherak Maldhari Sangathan (Banni Breeders’ Association), and claimed collective rights to the vast banni grassland under the Forest Rights Act. They secured their nature-based livelihoods through marketing camel milk amongst other strategies.

This is important, because without continued access to a healthy grassland ecosystem, they would have been far more vulnerable in the current crisis. According to Ramesh Bhatti of Sahjeevan “most of the Maldharis are coping well during the current crisis, especially if they are on their migration route. None have been infected by COVID-19; they are falling back on a traditional practice of not entering villages when there is a disease outbreak.”

Many are able to survive on milk and food they can find in the grasslands or desert. For those who require food kits or other basic needs, Sahjeevan has organised them on its own or with the help of the district administration. Sahjeevan has also convinced Amul and Sarhad Dairy to re-start buying camel milk, which they had stopped when the lockdown was announced.

The Abhiyan’s philosophy of community governance has been brought to 150 panchayats under its SETU programme. Started a few days after the quake, it helps bridge (setu in Gujarati) the gap between villagers and the government, enables empowered panchayats, and facilitates self-assessment and audits of local governance.

Over the last few years, this has been extended to urban self-governance in Bhuj, in a collaborative programme “Homes in the City” run by KMVS, Sahjeevan, and ACT along with Hunnarshala and Urban SETU. This bridge-building has helped direct relief where it is needed in the current crisis.

The Way Forward

The crucial importance of these programmes initiated by communities and CSOs is the focus on generating dignified, sustainable livelihoods that build on traditional skills, knowledge, and innovativeness.

This is completely opposite to the approach of several government programmes introduced after the earthquake, which focused on setting up big industries (mostly owned by outsiders).

Undoubtedly these units provide some employment to local people. However, the nature of this employment is insecure, since most of it is informal or unorganised, and liable to be terminated at any time. Like any capitalist undertaking, it entails the exploitation of labour and ecology.

Now, creating global markets for local crafts doesn’t move away from all these systemic problems. The dependence on external markets for sales has also increased the ecological footprint of the craft. It has also created a certain fragility in terms of sustainability, as the locals are dependent on global markets now stalled by the pandemic.

However, at least there is much greater local control over means of production, the satisfaction of working from home or local sites, and the pride of creatively continuing Kachchhi heritage.

As Sushma Iyengar, active since the beginning in Abhiyan, says these approaches “nudged the government to adopt a more sustainable reconstruction approach, with significant involvement of communities, CSOs, and some of the private sector.”

This setu approach, facilitated by CSOs and targeted towards the marginalised, is as important as that of enabling self-reliance and empowerment of community institutions. It builds the capacity for self-governance and direct forms of democracy.

One cannot simply replicate the Kachchh story elsewhere, it has its own cultural, ecological, and political uniqueness. But its general lessons are applicable across India. Crafts and other small-scale industries, agriculture, pastoralism, and decentralised energy and services all have the potential to sustain or create livelihoods for millions of Indians. But, as seen above, this requires fundamental changes in our economic and political functioning.

Can the COVID-19 crisis be used as an opportunity to make such a course correction?

Featured image courtesy of Ashish Kothari