Written by Anubhav Sachdeva

Certain high-profile cases have put the Supreme Court in the spotlight recently, and questions have been raised as to whether the court is performing to its full potential. In light of the fact that the Supreme Court had only 193 working days thus far in 2018 — partly due to an extended summer vacation that has been part of the court’s calendar since colonial rule — these concerns could be valid. Cases with significant consequences for public life are left waiting for an extended period, leaving citizens and the law in a state of flux.

The length of the apex court’s vacations seems to be the major cause of these delays. However, there are a few structural issues that plague the higher judiciary in India that prevents the institution from operating more efficiently. One such issue is how understaffed the higher judiciary is. It is currently filled to about half of the maximum number of judges possible.

Length of Vacations a Sticking Point

Judges at the higher levels of jurisdiction usually have packed workdays which accounts for time spent preparing for the next day of court as well. Although courts generally only function till 4 pm, there are some High Court judges who will sit in court till a later time in the evening to ensure that all the cases which were supposed to come up on that particular day are heard and do there is no spillover. Recently, Bombay High Court’s Justice Shahrukh J Kathawalla was in the news as his court sat till 3:30 am in the morning on the last working day before they broke for summer vacation. Justice Kathawalla regularly sits till night to clear the daily docket.

Having said that, not all judges are made of the same stuff, and most are already operating to their full capacity. Therefore, the sticking point that remains is the period that is demarcated for vacations, which many deem to be unnecessarily long. In 2018, the SC had a week off for each of the Hindu festivals of Holi, Dussehra and Diwali. It also had two weeks off in the winter, and a month and a half of summer vacation. ‘Vacation benches’ comprising of the junior judges exist, and they sit during the summer and winter vacation period.

Is this a court or a joke ??????

Even my daughter’s primary school doesn’t give this much Holidays pic.twitter.com/X7qctyTTzw— Rishi Bagree ?? (@rishibagree) October 29, 2018

While the summer and winter vacations seem reasonable and comparable to other apex courts’ calendar, granting the highest court of a secular nation with 7 days of leave on account of the three main Hindu festivals has been taken with a pinch of salt. The bench is constituted of judges of all religions, but festive occasions of all religions are not given the same official consideration.

The summer vacation period could also be shortened, but then the question revolves around managing the workload of judges. Judges, especially at the Supreme Court level, often have to deal with dense constitutional matters. These require a considerable amount of time, not only for deliberation but also to ensure that all parties to the case have their arguments heard. In such a situation, overworking judges could result in an unwanted dilution in the quality of justice meted out.

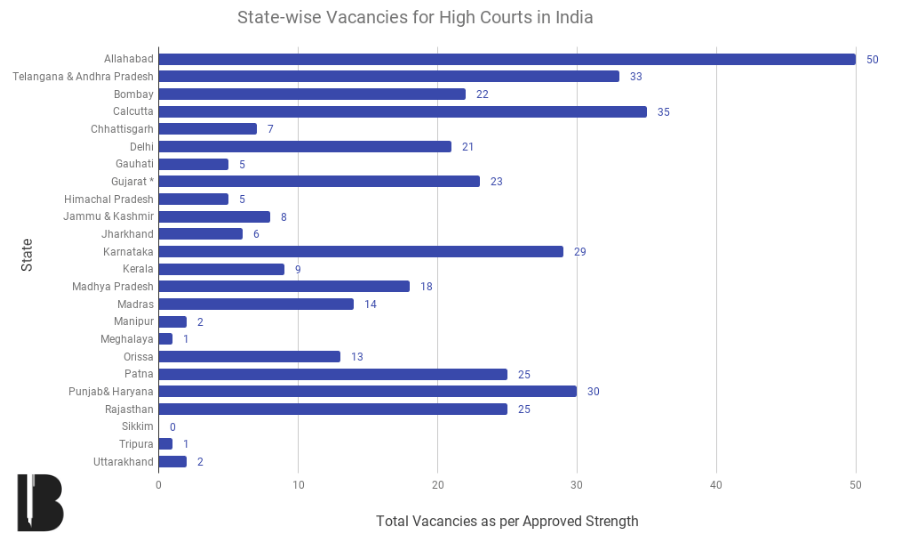

A Half-Empty Judiciary

The solution to this problem seems obvious. If a certain level of adjudication is to be maintained, while at the same time ensuring that judges are not overburdened, perhaps increasing the number of personnel working on cases might help. The higher judiciary in India has an incredible number of vacancies, and so courts are never even close to functioning at its full capacity. Statistics from the Department of Justice show that as of 1st October 2018, there are a staggering 434 vacancies in the High Courts of India. To put this into perspective, there are a maximum number of 1079 posts in these High Courts. This means that more than 40% of the posts in India’s higher judiciary are currently lying vacant.

So long as these vacancies remain, any attempt at providing alternative vacations to judges so that the court is almost always in session will be unfeasible. There is a five-member collegium consisting of the five seniormost SC judges who are responsible for making suggestions on appointments to the higher judiciary. It is a system that has been criticised by the court itself for being inadequate to effectively fulfil the function of monitoring the performance of judges all over the country. The government has also repeatedly stalled the collegium’s suggestions, further contributing to delays in the appointment of judges.

The Trials to Come

One solution that has been mooted is a division of the Supreme Court into two, according to certain specialised functions. These two courts would only serve their singular purpose – one would deal with constitutional matters which often require months of arguments and deliberation, while the other court would deal with the bulk of routine appeals that are heard. It has been suggested that a ‘branch’ of this appeals court could be opened in a location South of Delhi, so as to make justice more accessible to citizens.

Adopting such a system of specialised courts would certainly increase the efficiency of the apex court, allowing judges adequate time to focus on their assigned tasks. However, as with any judicial reform, this particular move would only be most beneficial if the issue of a high number of vacancies was addressed first. Only that can allow for a substantial number of judges to be available to divide functions amongst.

These structural deficiencies will continue to be levelled at the Supreme Court for being an inefficient institution. The first step could come from judges themselves recognising this factor and working as much as their minds and bodies allow them to. While in colonial times, they would have required two months off to be able to visit their homes, that is no longer the situation. India’s legal system is crying out for more personnel like Justice Kathawalla, who devote all their time to delivering justice to the nation’s citizens.

Featured image courtesy WikiMedia

[…] the pendency argument by pointing out that the staggering backlogs in our system are caused by a complex combination of several factors including judicial vacancies and poor case management. Merely taking away annual […]

786 sk firoj