Written by Swagam Dasgupta

Rijpal Saini, a father of four living in Pubsara, Haryana, desperately wishes for a stable income to support his family. Every day, he travels 32 km via public transport to Azadpur Mandi. Here, he waits along with hundreds of other mazdoors (daily-wage labourers) for thekedaars (contractors) to pick them up for a day’s work. Earning a meagre ₹ 120 a day - if he is lucky enough to be selected for work - his income falls well below Haryana’s minimum wage of ₹ 318.45 a day.

Millions of people like Rijpal are hopeful for new, secure and well-paying jobs. One crucial indicator of the government’s attempt to create new jobs is the annual budget. Hence, it is not surprising that the introduction of the 2018-19 Budget was preceded by debates and discussions in order to find an answer to India’s age-old question - where are our jobs? In an exclusive interview with The Bastion, Prof. Himanshu dissects the country’s unsuccessful history of job creation while posing a few solutions for the coming years.

Does the 2018-19 Budget Offer a Solution for the Lack of Jobs in India?

The budget promises various solutions spanning all three sectors of the economy, but these might not be as indicative of the creation of new jobs as expected.

Even if the government’s estimation of 5.5 million new jobs were true, (EPFO’s data is misleading), it’s crucial to note that this mainly includes jobs that have moved from the informal to the formal sector. Although formalization is integral to a healthy economy, it is not a substitute for new jobs. Himanshu also points out that the Budget doesn’t really deal with long-term solutions to the problem.

Why Can’t We Create More Jobs?

Himanshu sheds light on three bottlenecks in our economy that are stunting the creation of new forms of employment.

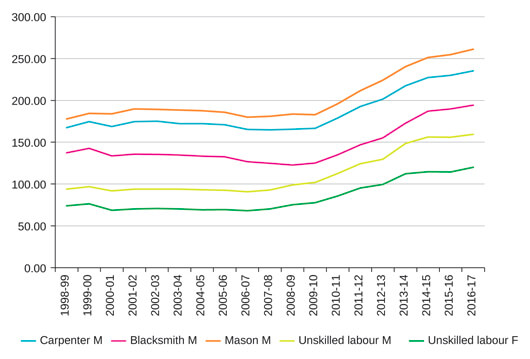

First, the growth rate of rural wages has slowed down; this can be attributed to the lack of rural demand. “Unless you pull up demand in the rural economy, you are not going to create [general] demand. If you are not going to create demand, then any amount of pushing money [into the economy] is not going to create more jobs”, says Himanshu.

Secondly, the share of private investments - a vital component of the economy - in the GDP has declined steadily for the past five years. Due to this, new jobs cannot be created with ease.

The fall in Gross Fixed Capital Formation since 2011 indicates the sharp decline in private investments. Source: World Bank

Finally, there exists a lack of policy incentives for labour-intensive small and medium enterprises. This is crucial since millions of people are hoping to move out of the agricultural or rural sectors. Hence, labour enterprises have the potential to create a large volume of jobs for the incoming workforce.

Does Rural India Hold the Key to Success?

Just by its sheer volume, the rural sector has the potential to make or break the availability of new jobs.

Rural India’s contribution to the Indian economy is by no means small. According to 2012 data, it adds to 51.2% of the total net value added in manufacturing. From the population size and economic contribution, it’s not hard to see there lies a massive scope for demand as well as the supply of jobs in the rural sector.

The graph depicts the rate at which India’s rural population is growing. Source: World Bank

Let’s take a look at an example; as incomes rise, many of India’s rural areas are utilizing electricity at the household level for the first time. Therefore, there is potential for a market consisting of low-quality electric goods such as fans, bulbs, electric heaters etc., to grow. This new and growing demand, aided by the multiplier impact, creates the need for incentivising labour intensive, small and medium enterprises that could create new jobs. As said earlier, after taking the massive population and economic contribution into account, it’s hard to deny that rural India’s demand holds a vital key to increased job creation.

Yes We Can Create More Jobs, but How?

To shift demand from agricultural to non-agricultural products, it’s crucial to increase surplus income in the rural populace’s hands. According to Himanshu, there are three ways to accelerate the process of surplus income.

First, there needs to exist an incentive structure, to encourage the production of low-end goods and services such as electric bulbs and construction services. Second, credit needs to be made more accessible, so that the rural sector can upscale its production. Finally, policies should be implemented that favour rural sector enterprises, to help them grow.

By putting these solutions into practice, India might finally win its historical struggle against its job drought. But, until then, Rijpal Saini and millions like him are forced to wait for the thekedaars (contractors) to pick them up for a sum of ₹ 120, every day.

Himanshu is the Assistant Professor of Economics at the Centre for Study of Regional Development, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. He is also visiting fellow at Centre de Sciences Humaines, New Delhi.