This article is the second instalment of Aparna Ramanujam’s two-part series ‘As We May Teach‘ which evaluates the privacy concerns and cognitive learning aspects of ed-tech services.

As the first part of this series acknowledged, technology has the power to transform education in ways previously considered impossible, through personalising learning, removing barriers to access, and improving digital literacy, among others. Intelligent technology can also minimize the demands on educators, such as objectively grading students, providing longitudinal analyses of student performance, unearthing correlations between student academic performance, and variables like SES/attendance, etc. This provides teachers with more time to invest in creating high-quality lessons. More than anything else, however, technology can make learning fun.

#India’s No.1 Learning App, Byju’s is Planning Global Expansion

The ed-tech firm has raised $150 million in funding in a round led by the Qatar Investment Authority. @BYJUS #Entrepreneurship #elearn19 #onlinelearning #onlineclasses #investments https://t.co/IPduJurYQS pic.twitter.com/X8JUpnzQTY— Global Shakers (@GlobalShakers_) July 11, 2019

In a recent survey, 89% of students in the US state that they use technology to aid learning in school more than once a week (with 57% using it every day) while a whopping 96% of school officials strongly support the use of digital learning tools in their school. However, when the same officials were questioned if their vehement support was rooted in evidence, only 18% agreed.

In other words, the majority of school officials believe that ed-tech is important even though they haven’t come across any supporting evidence, which begs the question: does any evidence exist?

Does Technology Help Us Learn Better?

A little digging reveals that there’s a decently-sized body of evidence supporting the use of digital learning tools-gamifying academic material has been shown to moderately increase learner motivation and facilitate creative thinking. Providing multimodal (or visual and auditory representations of the same concept) math problems to students, also enables more efficient problem-solving. However, these positive effects are tempered by more sobering findings on the value of ed-tech in the classroom.

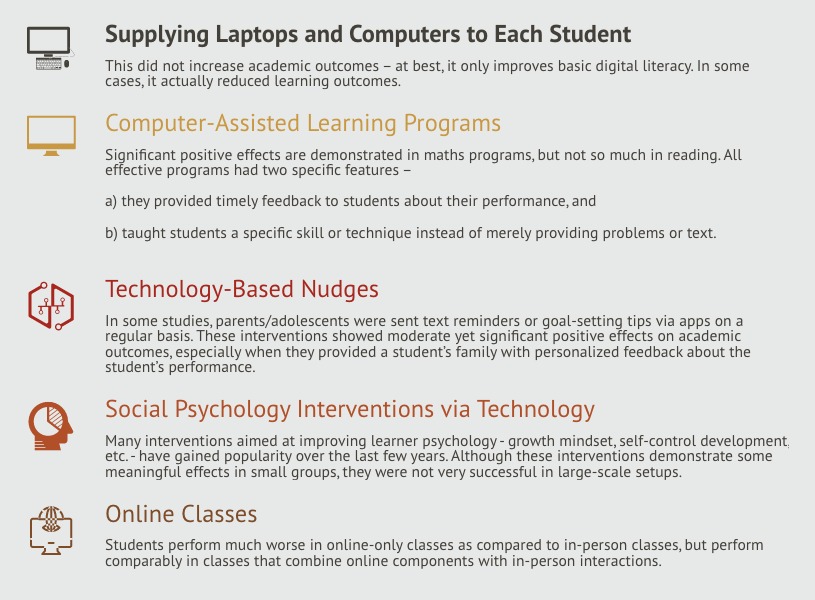

An independent evaluation of 126 interventions spanning several developed countries analysed five different ways in which technology was used in education-specific contexts.

Neuroscience also reveals that frequent use of technology-irrespective of context-may change our brains in ways we can’t fully understand yet. One study hypothesized that the fast-paced nature of technology may wire young brains to expect similar speeds while consuming information in other mediums. So, students struggle to pay attention in real-life situations since they aren’t as fast or as stimulating.

In another series of experiments, researchers found that technology leads to a phenomenon called “Cognitive Offloading”–that is, when we reduce the demands on our brain by transferring the work onto something else. We perform cognitive offloading in instances such as using a calculator or writing reminders on post-it notes. However, technology takes this to a new level – instead of remembering important information, we now merely remember how to access it. Although the long-term effects of this remain unexplored, it’s easy to see how this could permanently alter memory functions.

The Effects of Gamifying School on Learning

In addition, technology has been shown to impede social-emotional skills-one study showed that adolescents with reduced screen time were far better than their peers at recognizing and empathizing with others’ emotions.

The onset of puberty triggers a sea of changes in the brain, chief among which is the rewiring of the reward circuit. Feelings of pleasure and excitement are modulated mainly by a neurotransmitter called dopamine-a chemical controlling our perception of reward. Dopamine is also released when you win points in a game, thus triggering you to try and win more points. Although there are positive effects of gamifying academic content, it’s extremely likely that these games are training the neural reward circuit to want more dopamine.

This could have long-term consequences-if a student grows up needing frequent dopamine releases in order to learn, they may never develop intrinsic motivation (which is a marker of long-term success and satisfaction).

Perhaps Dr. Vannevar Bush’s omission of education from his list (of fields that technology would improve) was not an oversight. Though the possibilities are exciting, it appears that our enthusiasm for ed-tech is not tempered by realism as much as it should be–a fallacy Bush warns us of in his revolutionary essay.

Nevertheless, education technology clearly carries within it the real potential for good. Stronger footing in evidence may be all that’s needed to harness technology and put it to good use in education. To quote Bush:

“The applications of science have built man a well-supplied house, and are teaching him to live healthily therein…it would seem to be a singularly unfortunate stage at which to terminate the process, or to lose hope as to the outcome.”

Featured photograph courtesy of Hal Gatewood on Unsplash

Like your article… Technology is the most important thing in today’s life. I am sure technology is very helpful to learn Nuro-science..

I mean a blended approach ..

Edtech, combined with physical activity based learning, can add significant value to the learning outcomes. What’s needed is a bonded approach