There is a lot of uncertainty over how schooling will look like post-lockdown. Can schools run full scale? Will learning happen through TV and/or the Internet? What will happen to those who can’t afford to pay school fees? Will children from private schools shift to public schools?

For perspective, as of 2020, about 30 to 40 per cent (~79 million children) study in ‘Affordable Private Schools’ (APSs), which charge between ₹500 to ₹3000 a month. These schools are critical actors in enabling every child’s access to education of a certain quality. APSs are especially significant for a country where 27 million children are born every year and 270 million children (discounting dropouts) need an education between grades 1 and 10.

Like other small businesses, the ~270,000 APSs in India are heavily dependent on their patrons’ fees to keep their operations running. Post-lockdown, their patrons — parents from low-income backgrounds — have been badly affected. A study by Tata Trusts found that ~30% of households from impoverished backgrounds may be forced to withdraw their children from schooling due to financial distress. The proof is in the pudding: APSs have already lost about 25-30% of their revenue, which has made it difficult to pay teachers and other staff.

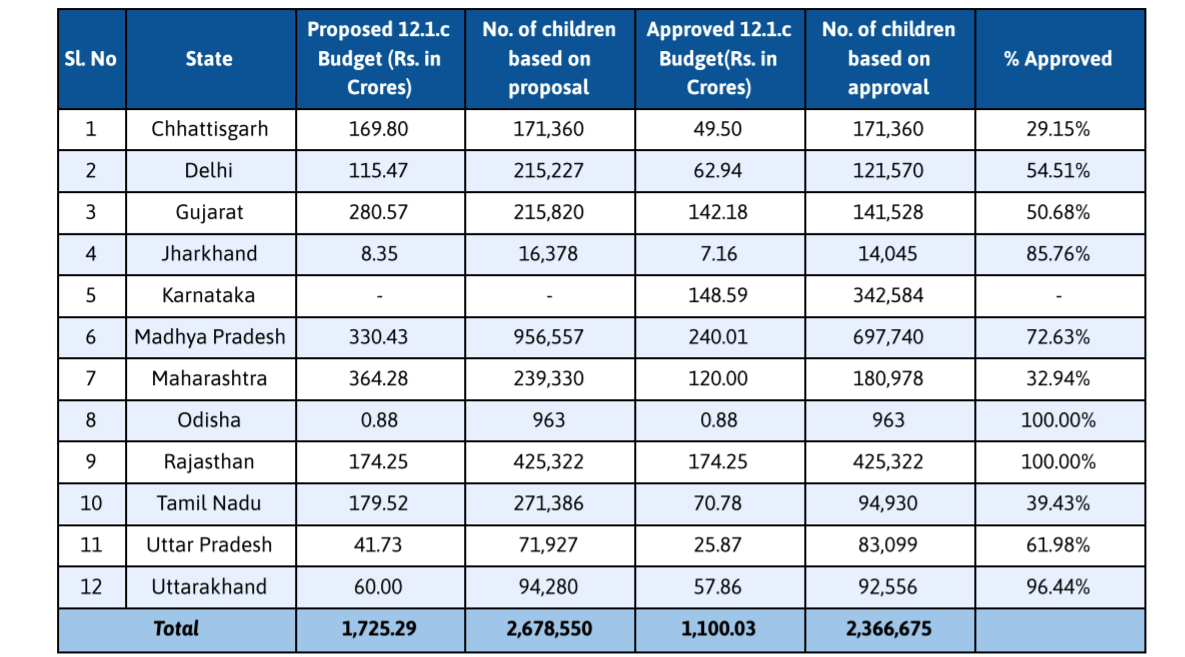

So, like any other industry, school education also requires a stimulus. One potential game-changer could be to reorient our focus on Section 12(1)(c) of the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2009. Commonly known as ‘25% EWS Reservation’, it mandates that the costs of a minimum of 25% of seats/students in private unaided schools are borne by the government. An estimated 41 lakh students from Economically Weaker Sections (EWS) and Disadvantaged Groups (DG) have benefited from this provision since states have begun implementing it.

Why Focus on 12(1)(c) After a Pandemic?

Besides its constitutional mandate and intent of creating more inclusive classrooms, the government needs to implement this provision in full spirit, especially in a coronavirus-hit education ecosystem. Here’s why.

First, consider the costs of educating. If the government stopped supporting 25% per cent of EWS and DG students in these classrooms, there is a high probability that they will be forced to drop out and join cheaper public schools. This may happen even with the general students in APSs because they also come from low-income backgrounds.

While some may see this as an opportunity to increase our enrolment figures in public schools, in most cases, the cost of supporting a student in public schools is more than the reimbursement paid by the government to APSs. So, for every child that moves to a public school from an affordable private one, the spend will be higher. A CCS report cites that 70% of private schools charge less than how much the government spends per child.

On the Fence? Read: Public Good, Private Responsibility? The RTE’s EWS Reservation

Second, the capacity for quality education. There are cities where APSs account for 50 to 60 per cent of all admitted students. A move away from these schools could mean that 50 to 100 per cent more students apply across government schools that are already reeling under inadequate infrastructure and poor student-teacher ratios. While these issues can (and should) be solved in the long run by investing in capital expenditure for building schools and increasing the number of teachers, such a shift in schooling will mount tremendous pressure on the capacity of the public education system to ensure high quality.

Third, we cannot forget that APSs are an ‘industry’. Alongside supporting the education they offer, APSs require a stimulus from an economic standpoint. The 270,000-odd APSs in India employ anywhere between two to three million citizens as teachers, administrative staff, etc. Even if 20% of these schools shut down, three to five lakh jobs could be in jeopardy. Most teachers in these APSs are women, which will directly impact the finances of several families as well as reduce the overall participation of women in India’s workforce.

Isn’t Implementing 12(1)(c) Too Cumbersome?

Albeit landmark legislation, ensuring that every child receives a quality education is a continuous process that gets complicated when liaising with private entities. The government can fine-tune some processes to implement the ‘25% EWS quota’ more effectively post-lockdown.

First, register all private schools. States like Delhi, Gujarat and Chhattisgarh have created online processes for registering private schools for implementing 12(1)(c); other states would do well to follow suit. Registration will also enable states to track the health of private schools and be able to collect additional data on them, such as the fees that have been collected over the last few months. This could be beneficial in areas/blocks/districts that are prone to student migrations away from APSs by creating processes for schools to absorb students.

Second, register all students. With social distancing norms in place and a protracted reverse migration underway, an online portal for students to register for availing Sec 12(1)(c) will be beneficial. States like Gujarat, Chhattisgarh and Delhi are already doing so. At the same time, there could be a relaxation on the documents required for availing the reservation for this academic year, given that submitting documents requires access to technological infrastructure and the ability to use it. Conditional admissions can be made with a mandatory furnishing of documents at a later, more feasible date.

Some states like Rajasthan have even relaxed the income limit from ₹1 lakh (before lockdown) to ₹2.5 lakh post-lockdown. This will allow more students to apply and avail the benefits under the provision.

Third, states must rethink the budget for books and uniforms. Sec 12(1)(c) mandates that the state provide these for EWS students; post-lockdown, a part of this could also be channelled towards giving these children masks and booklets with safety instructions. Awareness needs to be built for the future and masks need to be provided now to keep students safe.

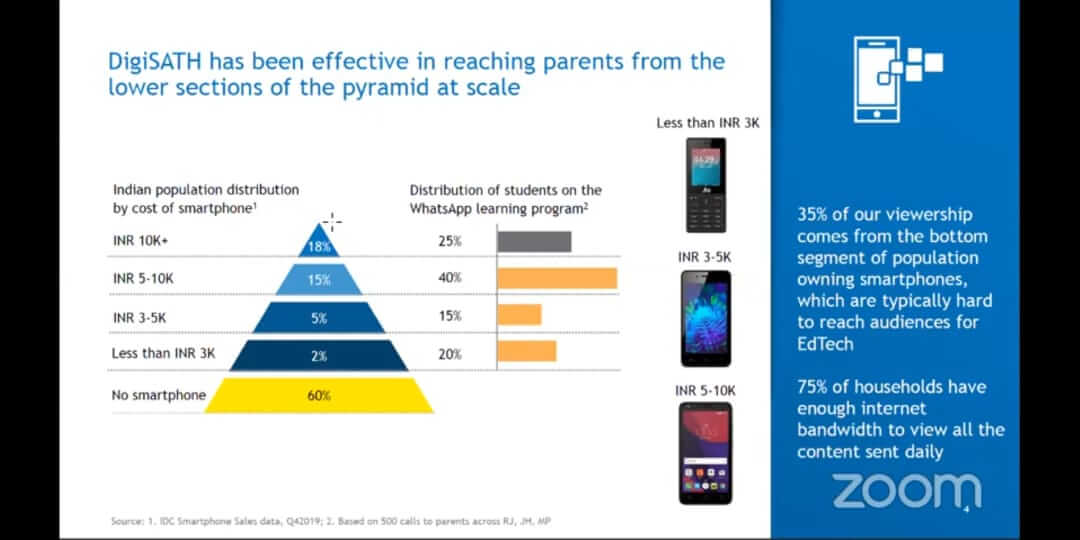

A more enterprising idea is to utilize this year’s ancillary budget to provide students/families with a smartphone. In case lockdown is extended or schools don’t function at full capacity, the smartphone can become a channel to provide content and access to the students.

You May Also Like: How Corporation Schools in Chennai Are Bridging the E-Learning Gap

Fourth, the government must reimburse schools for previous years’ admissions under the provision. States like Rajasthan, Uttarakhand and Madhya Pradesh have had more than 70% of their proposed budgets approved, and others even have online reimbursement modules alongside their student trackers. This will fasten the reimbursement process, which goes a long way in keeping an APS afloat.

Fifth, the government must take care of existing RTE 12(1)(c) students. As with Chhattisgarh and Delhi, other states could extend this provision (from Grade 8) up to Grade 12. This will ensure that EWS students will be able to continue and complete their schooling. Parents and students are going to find it difficult to make the switch to a new school or pay general fee amounts amidst the pandemic-induced financial uncertainty. Books and uniform money could be paid by the government at the start of this academic year.

Almost 2 million seats come under the RTE’s Section 12(1)(c) every year. A maximum reimbursement per student of ₹10,000, or an average of ₹5,000, translates to ₹1000 to ₹2000 crore per year. For eight years of RTE-mandated schooling for 25% of our students in private schools, that figure amounts to somewhere between ₹8,000 to ₹16,000 crores. Only 50% of these seats get filled every year. All of this goes to show that swiftly implementing and monitoring this constitutional provision will go a long way in ensuring that students do not drop out post-pandemic. Affordable Private Schools will be able to continue operating, crores of jobs can be saved and pressure on our already strained public education system can be significantly reduced.

[…] in the education sector will not be unprecedented. The Right to Education Act, 2009 mandates a 25% reservation of seats in private unaided schools for children from economically weaker and disadvantaged backgrounds. A welfare-oriented state […]

Hi …it’s good to see that steps are being taken to provide free education to EWS children in the pandemic time which is already going on in Delhi from last many years. But it is very strange to see that none of the organisation, government, political parties, NGO’S have any interest to think about Teachers and the administrative staff. Increasing the yearly salary limit for EWS will take away many children from the normal category to EWS category which will directly affect the finances of a Public or a Private School and this will affect the teachers and administrative staff salaries. No concern about them …no policies for the school staff……we are expected to teach free as if we do not have families to run…as if we all have left the world behind and are in to teaching only without taking care of our near ones. #Shamelessindiansystem

Hi Shweta,

Valid point - teachers welfare should also be looked into as well.

RTE 12 1 C reimburses schools their full fee per student (for majority of them) - so that will or should not affect the finances of the school - schools are getting the fee from govt instead of parent. Also, most states dont admit more than 25% of students under this provision (even though the provision is for a minimum of 25% and not max of 25%)- and hence there wont be more students moving under this category by increasing the income limit - this will only enable more parents to access the provision.