I was just a young boy when I caught my first fish. I felt excitement, anticipation and adrenaline all at once, as if I had scored the first goal of a high school football game. While it was far too long ago to go into specific details, this early intimacy with nature left long-lasting impressions and shaped my worldview. That first fishing experience with my father had me hooked! My father and I would keenly survey river runs, rapids and lakes searching for signs of fish. Over the years, I’ve had countless such opportunities to familiarise myself with the ebb and flow of rivers and the rich nuances of freshwater habitats.

So much so, that to me, urbanites seem like fish out of water, entirely alienated from the natural world. ‘Nature Deficit Disorder’, an increasingly common term of reference, is ever-present. It seems only a fortunate few will have the opportunity to explore, be intrigued by and truly immerse themselves in nature at an early age. This primeval stimulus of our senses is essential in building natural intelligence and ensuring the early development of individuals and the society they comprise.

The Heart of the Matter

In case you haven’t guessed by now, I am an angler and a proud one at that too. An ‘angler’ is a recreational fisher, and much like the fish that they seek, they too come in a variety of shapes, sizes and colours. Not all anglers are cut from the same twine, so to speak. Some harbour notable respect for fish and nurture conservation sentiments for aquatic species and water bodies alike. Others might merely want to have their plate full of the day’s freshest catch. I certainly identify with the former. More than long-term principles or short-sighted desires, the attraction to angling is, without a doubt, the sheer thrill of it.

Today, I find that the proposition of using ‘recreational angling as a tool for conservation’ has been hastily and unduly disregarded in the context of conservation in India. This piece of writing is an attempt to channel innumerable hours spent in research, dialogue with peers and state authorities, self-introspection, field studies and angling itself in order to explain the link between angling and freshwater conservation in India. Anglers need healthy fish stocks; healthy native fish communities are an indicator of healthy rivers and lakes. Now, allow me to offer you a glimpse into the heart of the matter.

Mesmerised by Mahseer

I must confess that no amount of conservation workshops, training programmes, internships or lectures that I have attended has compelled me to stick by a career in conservation as much as the experience of catching my first mahseer has. Only images can do justice to the brilliance of this species of freshwater fish.

There exist 16 known species of mahseer, and it is with great pride that I proclaim that half of them are endemic to Indian rivers. These fish are migratory, using rivers as ‘monsoonal highways’ to reach their spawning grounds. In doing so, their ecosystem services are felt over large distances. For example, predator-prey balance and nutrient cycling are two important phenomena that regulate the resilience of aquatic ecosystems from within. Being mixed feeders, mahseer shift their diets between plant and animal-based sources, thereby playing a vital role in optimizing these natural processes. These fish are highly sensitive to water quality and pristine habitat conditions, so if mahseer are present in a river, one can be certain of superior water quality and healthy ecosystem.

Mahseer are also a species closely linked to religion. Karnataka itself has nearly 21 temple sanctuaries where mahseer are revered.

From a commercial point of view, mahseer are less popular in comparison to their close relatives in the carp family as an aquaculture species. But, by virtue of holding titles such as the ‘Top 20 aquatic megafauna of the world’ and the ‘Tiger of the River’, they are viewed as one of the world’s premier freshwater game fish, making them important for conservationists globally.

The first large mahseer I caught was quite the spectacle. It had my fishing reel screaming, my hook was refashioned into a sort of modern art exhibit, my back was cramped for days and my mind was absolutely mystified in equal parts of awe and disbelief! All of this, while precariously positioned on a sun-baked rock in the middle of the Cauvery river with rapids, birds, trees, elephants and families of otters viewing a grand sunset. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again — hooked for life! It was just that simple.

Catch and Release Angling: Worldwide and in the Cauvery

‘Catch and Release Angling’ is becoming increasingly popular among some angling circles in India. It is a practice wherein fish are caught and released while taking utmost care for their post-release wellbeing. It is often considered a recreational activity, but has developed into a legitimate fish conservation strategy in many countries. Such angling is governed by a list of rules or guidelines popularly referred to as ‘Angling Best Practices’. In an informal setting, the accepted guidelines are carefully honed from years of experience and are socially enforced as a code among fellow anglers.

Where recreational angling has been adopted by governments as a legitimate activity — like Canada, Australia, many European countries and the US — angling best practices comprise an independent branch of scientific research. A recent study conducted on mahseer caught using rod and line in the River Cauvery used various indicators including radio-telemetry to investigate their post-release mortality. The research demonstrated that mahseer are robust to angling and will survive after being released; that being said, existing angling best practices could still be tweaked to reduce stress on individual fish.

Time and again, I have introduced folks from all walks of life to ‘Catch and Release Angling’ and have seen how it instantly grips them with excitement and instils a curiosity for rivers and freshwater ecosystems. This is the value of recreational angling as an educational tool; it creates a platform to engage diverse target segments in conservation work.

This is not some desperate and naïve spiel from an avid angler seeking justification. In the USA alone, 30 million freshwater angling licence holders turned over a whopping 720 million USD in sales impacts in 2018. Almost all western countries promote recreational fishing as an activity closely linked to conservation outcomes. What drives the conservation value for anglers? It’s simple. There can be no angling without fish. Hundreds of recreational angling initiatives worldwide that have demonstrated success in the areas of community building, collective action, environmental education, habitat restoration and protection of indigenous fish species. For example, the state of Illinois in the US was the first to sanction competitive ‘bass angling’ as a high school sport in 2009. Today, many states have followed suit, and thousands of children now have access to the outdoors and the opportunity to build a relationship with nature. As other states have followed suit, bass fisheries are thriving across the country.

There is an exemplary case of community-based conservation in the forests of Guyana, South America, thanks to a rare living fossil, the Arapaima fish. People from all across the world come to the Rewa village community’s eco-lodges to attempt to catch (and release) this ‘uncatchable’ monster fish. With a little help from the international angling community, this model has become sustainable both economically and ecologically. Here’s a beautifully animated film that depicts this success story:

Similarly, the community in Anaa Atol in French Polynesia have adopted catch and release angling in their shallow flats as an eco-tourism model with great success.

I hope that by this point, I have the attention of the conservationists amongst my readers. What is remarkable is that all these examples are supported by an economic model centred around ‘Catch and Release Angling’.

Karnataka: Home to the World’s Largest Mahseer!

In India, a variety of outfitters offer recreational angling as an experience at a much smaller economic scale but far greater ‘enjoyment’ factor, in terms of fish diversity, wilder landscapes and tropical climate. Perhaps the most significant Indian example of a recreational fishery is the former Cauvery Fishing Camps (in Ramanagaram district of Karnataka) which offered the world’s best mahseer angling for over four decades. It was managed under the aegis of the Wildlife Association of South India (WASI) and M/s. Jungle Lodges and Resorts. People from across the globe opened up their wallets for a chance to catch the world’s largest mahseer.

Because angling in India is barely in its infancy and not as yet a formalised or regulated industry, the exact annual turnover from angling-based activities at these camps is not known. However, I am informed by a reliable ex-Jungle Lodge manager that they reach into the eight-figure league (INR). That money could be channelled again towards conserving the very same stretch of the river via river patrols, vigilance camps, community building, conservation outreach, training local fishermen as professional guides, strict compliance on angling best practices and the budding network of anglers themselves.

Today, the return on this investment would have been a level of structure and organisation that discourages unsustainable fishing practices and other illegal activities such as animal poaching and mining. The recreational fishery would be self-sustained, we would have bigger fish, the river would be protected, aquatic life would thrive and local communities could have benefitted from the programme via monetary compensations and an instilled sense of ownership over resources. It has all the making for a successful community-inclusive conservation model that is independent of external funding.

So, What’s the Catch?

I cannot turn a blind eye to the potential risks of advocating angling in India. It demands a properly enforced conservation strategy and cross-collaborations among key stakeholders: the state authorities, anglers and the scientific community.

The opening up of the Indian market to western outdoor activities brought easy access to an unimaginable array of fishing tackle — rods, reels, lures, baits, boats, sonars, drones, underwater cameras, landing nets, floating pontoons, braided line, mono-line, the list goes on. Sometimes, I wonder if it isn’t all a bit much. In the absence of a formalised conservation context, the angling industry runs the risk of having a negative impact on freshwater ecosystems.

From a conservation point of view, there isn’t a better time and relevant context for intervention. Without being sensitive to such facts, we run the risk of irreversibly diminishing our native fish species. In May, a 38kg humpback mahseer (pictured right) was caught on a handline and sold in the local market in Kodagu district of Karnataka. The specimen was a relic and one of the last remaining of its kind. The youth group who had fluked the catch were completely unaware of what they had done and mistook it for a catla fish.

Social media has also changed the core and character of an angler’s conduct. I have observed a marked shift, from sensible reservation exercised by an unwillingness to disclose one’s favourite fishing spots, to openly sharing a never-ending trail of pictures of impressive and rare fish caught in alarming numbers. Opportunity for a nice distribution study? Perhaps. But, improper information on Catch and Release best practices can have an irreparable impact on native species. There are lessons to be learned and ecological impacts to be considered.

Navigating Unchartered Territory

At the outset, the idea of encouraging recreational angling as a management tool in Indian lakes and rivers might come across as unsettling to some. To the contrary, I argue that the benefits outweigh the costs by a huge margin. Some opine that angling and conservation cannot go hand in hand, as the activity is inherently invasive. It would be naïve to protest that statement as untrue, but before committing to an opinion, do consider the following issues that are ‘out of sight and out of mind’.

While the harvesting of mammals, birds and reptiles is illegal, attracting penalties and/or jail time, as per the Indian Wildlife Protection Act (1972), fish species do not share the same protection status.

Let’s face it, in India, fish are a food source and a livelihood. Lakes and rivers are primarily managed through government tenders released for the stocking and harvest of fish. The aquaculture sector in the country largely focuses on five commercial species, collectively called the ‘Indian large carps’; they are grass carp, common carp, mrigal, rohu and catla. There is little consideration for the ecological impact of systematically stocking thousands of individuals into an ecosystem.

Additionally, there is an array of alien and alien-invasive species like the African catfish and tilapia that have established in our wild waters. Talk to the fisher-folk on the lower Kabini or Talakad stretch of the Cauvery and they will tell you that their catch is almost entirely composed of this highly invasive African Catfish (which has no market value, hence tragically released alive to continue breeding freely). Talk to anglers operating in the same area and they will tell you that mahseers are now extinct there.

These issues are further confounded by our constant manipulation of water bodies in the name of ‘developmental projects’; rivers are brazenly dammed, drained, diverted, mined, polluted, ‘interlinked’. At a local scale, they are indiscriminately bombed with dynamite, netted, poisoned and electrocuted for fish. Among us, who feels the full impact of this mismanagement? Who owns our freshwater resources and is accountable for their ecological health? What is India’s plan for managing freshwater bodies in the future? While there are many parties debating these issues, the Indian angling community has been getting increasingly vocal in advocating for clean water bodies and the conservation of freshwater species.

Angling for Conservation

In many parts of the world, anglers are the most prominent stakeholder group for aquatic ecosystem concerns. They are often considered the ‘memory of a river’, what with being the only ones able to recount catch sizes, good and bad fishing years or constantly advocating for better functioning aquatic ecosystems. What if the angling community in India has to offer a supplementary livelihood option for fishermen that has minimal impacts on fish stocks and incentivises conservation of native fish species? In fact, anglers love native fish, thereby encouraging a stock of native species in water bodies that they frequent. After working closely with an angler group networked by Wildlife Association of South India (WASI), I am convinced of the wonders it can do.

Over the past six years, I have been working closely with the Wildlife Association of South India (WASI) on a project focussed on research and conservation strategies for mahseer of the Cauvery. One particular species endemic to the Cauvery basin has taken centre stage: the largest of all mahseers, the humpback mahseer.

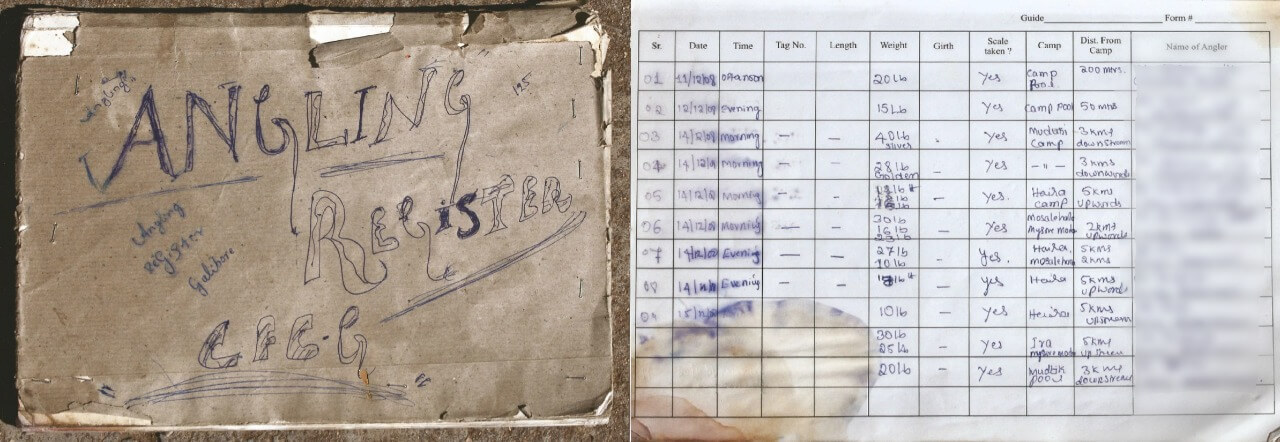

It has emerged as the ambassador for fish conservation in the basin and is listed as ‘Critically Endangered’ under the IUCN RedList thanks to a study by a team of researchers from India and the UK. In fact, the study would not have been possible without the angling records maintained by the Cauvery Fishing Camps between 1998 and 2012, which formed the basis. It revealed a plummeting crash in the population of humpback mahseer and a simultaneous release of a second mahseer species present in the river, the blue-fin mahseer. This was shocking, to say the least, but it highlighted the humpback mahseer as a species in need of immediate conservation attention.

Today, these catch records remain the only source of data on past population trends of these species of fish. For erstwhile fishery managers to have accomplished this long-term documentation within the framework of a profitable economic model is an achievement to be noted and a lesson to be learned. Even now, meticulous catch records are maintained in the registers of ‘WASI Waters’ that offers robust insight into long-term fish population trends, free of cost.

Formidable Undercurrent: Conservation, Collaboration and Community

In an effort to study the current distribution of the humpback mahseer, the WASI community launched a series of research expeditions across the Cauvery basin. These expeditions were ensued with the support of the Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Kerala State Forest Departments and are being conducted smoothly, safely and regularly at minimal costs to the organisation. The anglers bear the costs quite enthusiastically.

Altogether, after thousands of man-hours of sampling, we were able to create a morphological and genetic database of mahseer from across the basin. We were also able to create interactive maps of critical habitats and document traditional knowledge on mahseer ecology collected from fishermen.

Perhaps the largest boon from an organised initiative would be the education and awareness potential to ‘hook and reel in’ people’s interests in the conservation of freshwater ecosystems; not only for schools and colleges, but forest managers, corporate groups, local communities and the numerous water resource authorities associated with freshwater bodies in India. WASI’s work has also shed light on the status of other ‘Endangered’ fish species endemic to Peninsular India, such as the silund catfish (last known population from the Cauvery basin), pink carp (‘Endangered’, IUCN) and Cauvery catfish (a species that is possibly new to science).

Reeling It In

It is my hope that this article reaches managers, conservationists and scientists alike, so they may build on the interest of the angling community and consider the implementation of available market-based tools such as Catch and Release angling for aquatic conservation and sustainable livelihood support. The scope for India to have a structured angling programme that is informed by science and conservation holds greater promise in terms of far-reaching impacts and results. Being an angler, researcher and freshwater ecologist myself, the WASI expeditions demonstrates that research into cryptic and understudied species becomes logistically viable when working with anglers. Angling camps and angling competitions become a reality in the mapping and removal of invasive fish species. Furthermore, a ‘presence on the river’ means protection from unsustainable fishing practices and supplementary income for local fisher-folk from angling-based activities.

Going by what we’ve learned from working on mahseer in the Cauvery, a little organisation and planning can go a long way. It can employ anglers in the long-term monitoring of water quality and fish populations, without incurring any significant monetary costs. It can also support the local economy and aquatic ecology by incentivising new revenue streams and maintaining healthy lakes and rivers.

We have opportunities for participatory conservation and incentive-based management of freshwater bodies, as well as new perspectives on managing our aquatic ecosystems and indigenous fish species. What has always been essential then becomes inevitable, which is to preserve the integrity of our freshwater resources, while mobilising people to take ownership of local fisheries. I remain positive and enthusiastic, with proven surety, that Indian anglers are sufficiently motivated to be at the forefront of this stewardship. I came across a quote written by Henry David Thoreau that thought-provokingly describes the motivations of the angling community:

“Many men go fishing all of their lives, without knowing that it is not the fish they are after”

Regardless of whether they are after recreation or conservation, here is an activity that marries modern human society with advocacy for clean and healthy freshwater bodies. The time has come for India to write a new chapter in the management of lakes and rivers — one that looks beyond aquaculture and ranching. The time has come to forge ahead in pursuit of a broader vision that prioritises habitat restoration, invasive species management, fish-stocking policy, livelihood support and eco-development projects. The time has come for Indian conservationists to get hooked.

Featured image courtesy Barbara van der Ven

Superb! This article clearly articulates the importance of conservation-based angling for fisheries and the communities and individuals that value them. India needs more voices like this! Excellent!

Sngling as a sport and recreation is catching up fast…modern equipment and loads of information available on the net. However concerted efforts and creating awareness among stakeholders are equally important. Involvement of local populace is the key…

What an eye opener. Well written.

Great story. Freshwater fish are disappearing fast globally. Let’s try to preserve these amazing mahseer!